Homeless in US: A deepening crisis on the streets of America

They seem to be almost everywhere, in places old and new, no age spared. Sleeping on cardboard or bare ground, the homeless come together under bridges and trees, their belongings in plastic bags symbolising lives on the move.

Many have arrived on the streets just recently, victims of the same prosperity that has transformed cities across the US West Coast. As officials struggle to respond to this growing crisis, some say things are likely to get worse.

BBC

BBC

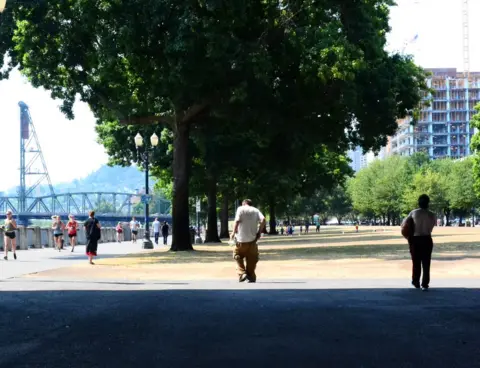

Vibrant Portland, Oregon's largest city, has long lured many. It is the City of Roses, of pleasant climate, rich culture and progressive thinking. It is also an innovation hub, part of what is called Silicon Forest, and new residents have moved here in these post-recession years attracted by its high-tech companies and their well-paid jobs.

But the bonanza, unsurprisingly, has not come to everyone.

BBC

BBC

Booming demand in an area with limited housing offers quickly drove the cost of living up, and those who were financially on the limit lost the ability they once had to afford a place.

Many were rescued by family and friends, or government programmes and non-profit groups. Others, however, ended up homeless. The lucky ones have found space in public shelters. Not a few are now in tents and vehicles on the streets.

"Even though the economy has never been stronger," Mayor Ted Wheeler, a Democrat, said, "inequality [is] growing at an alarming rate and the benefits from a [growing] economy are increasingly concentrated in fewer and fewer hands... We have increasing disparity all across the United States, and that's definitely impacting people."

BBC

BBC

His city is indeed not alone. Homelessness has increased in other thriving West Coast cities that are destinations for young, well-educated workers, like San Francisco and Seattle, where the blame has also largely fallen on rapidly rising costs and evictions.

Exact numbers are always hard to come by but 553,742 people were homeless on a single night across the US in 2017, the Department of Housing and Urban Development said, the first rise in seven years. (The figure, however, was still 13% lower than in 2010.)

Declines in 30 states were overshadowed by big surges elsewhere, with California, Oregon and Washington among the worst. Los Angeles, where the situation has been described as unprecedented, had more than 50,000 people without homes, behind only New York City, which had some 75,000.

BBC

BBC

Joseph Gordon, known as Tequila, has lived in a homeless camp called Hazelnut Grove since its creation in 2015, when Portland first declared a state of emergency over the crisis. "It's very scary. [The] people I have come across," said the 37-year-old, "are from every single walk of life. And the homeless population is getting bigger and bigger."

Multnomah County reported 4,177 people homeless on a single night last year, a 10% rise from 2015 - many believed the number was even higher. Exposing tensions, the president of Portland Police Association controversially said in July the city had become "a cesspool", a comment the mayor dismissed as "ridiculous".

Tequila arrived from Cincinnati, Ohio, in 2011 and said they (Tequila is a transgender man and asks to be referred by this pronoun) became homeless after losing the apartment they shared with a former violent partner.

BBC

BBC

"Being out on the street you deal with all sorts of things [like] having to relax with living with rats. You also start to appreciate running water or when you can go to the bathroom anytime you want," said Tequila. (People usually thought Tequila was Mexican because of the colour of their skin, and the nickname was in reference to Jose Cuervo, the tequila brand.)

The self-governed community of small wooden structures next to a highway had more than a dozen residents, half of them with some sort of income, Tequila said. "If there was access to actual affordable housing they would take it."

In Portland, the rent of a one-bed flat is, on average, $1,136 (£867), which is out of reach for those who rely on Social Security cheques, topped at $735 locally, or earn the minimum wage, $12 per hour. (Officials said half of the 1,300 units to be created would be reserved to those with extremely low income.)

BBC

BBC

Elderly people and minorities have been disproportionally affected, according to a study by Portland State University, which said technology could result in thousands of low-paid jobs being cut, probably making things even worse.

"We have a housing market that's really unaffordable for folks at the lowest income level," said Shannon Singleton, Executive Director of Join, a charity that helps homeless people return to permanent housing. "There's a real lack of hope. Folks are struggling to see the ability to end their homelessness and get back in the [market]."

While some defend Tequila's camp as a model for an alternative solution, authorities have said it will, eventually, have to go. No date has been set yet but there have been troubles with nearby neighbours recently.

BBC

BBC

Homelessness, in Portland and beyond, seems to be more visible than ever. Residents are growing frustrated with the smell of urine, human faeces and abandoned objects littering public spaces and, sometimes, their own doorsteps. In certain places, there is the feeling that this is a fight being lost.

But this is a crisis long in the making. Cuts by the federal government to affordable housing programmes and mental health facilities in the last few decades helped send many to the streets nationwide, officials and service providers said, as local authorities were unable to fill the gaps. The current affordability problem is now adding to it.

BBC

BBC

Australian academic Philip Alston, the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, travelled across the US for two weeks last December in a mission that included visits to Los Angeles and San Francisco. It resulted in a scathing report in which he said the American dream was, for many, rapidly becoming the American illusion - the Trump administration strongly criticised his findings.

The future, he warned in an interview, did not look promising. "The federal government's policies under this administration have been to cut back, as much as possible, on various housing benefits and I think the worst is probably yet to come."

Other rich countries have faced rising homelessness, too, as the most vulnerable feel the burden of austerity policies, rising costs and unemployment. But in most parts of Europe, for example, there was still a "robust welfare safety net", Mr Alston said, to help those at risk. "In essence, if you're in Europe, you get access to necessary health care, psychological, physical rehabilitation... That contrasts dramatically with the US."

BBC

BBC

Across the country, many say the homeless are unfairly targeted by authorities and that they end up criminalised by their status when accused of offences like sleeping rough, begging and public urination. In August, a federal appeals court ruled that people could not be prosecuted for sleeping on the streets when there was no shelter available.

In Portland, the police oversight agency is reviewing how officers interact with homeless people - many suffering from drug addiction and mental health issues - after a report suggested they accounted for 52% of the arrests recorded last year, despite being a tiny fraction of the local population of some 640,000.

BBC

BBC

"People are simply trying to survive and they don't have means to do so," said Kimberly McCullough, Policy Director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Oregon. "We're seeing a crisis of our humanity and how we're going to treat and help each other."

Tequila, however, was not surprised. "Of course there are tensions," they said. "If a police officer is having a bad day... the easiest target is a homeless person, especially the ones who are by themselves."

BBC

BBC

Back at Hazelnut Grove, Tequila, who had found a part-time job, was asking for donations of toilet paper, garbage bags and shampoo. They were gathering documents to join a local affordable housing programme but did not expect to move from the camp any time soon.

"A high homeless situation is not a good [sign], especially when you're the richest country," Tequila said. "There's very little hope. It's a dire situation."

Follow Hugo on Twitter: @hugobachega