Syria earthquake: Survivors in Idlib feel forgotten

BBC

BBCSedra remembers the moment the earthquake struck.

The 13-year-old was out of her wheelchair, asleep inside her home in north-west Syria. She and her brother Abdullah could not get to safety.

"We screamed for help and no one could hear us," she tells me. "Everyone in the building had left, but we were stuck in there because the door handle broke."

"I thought I had lost my family," recalls Ali Muhammad, Sedra and Abdullah's father.

"The hallway was filled with rubble, but we managed to carry the children out and lay them down outside on solar panels that had fallen into the street."

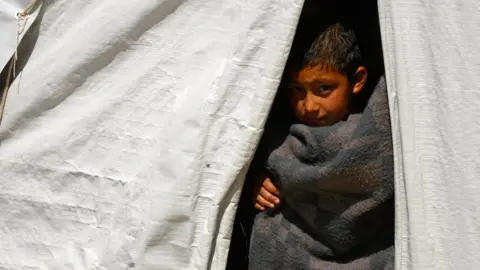

"They were terrified and crying. We covered them in blankets, but the rain was pouring heavily."

The family's home was so badly damaged that they are now living in a tent.

"Life right now is very difficult. Living in tents is miserable, but we thank Allah that we are alive," Ali says.

Sedra and Abdullah both have cerebral palsy and osteoporosis, and need special care. But now there is no bathroom for them, no kitchen, no water.

It is difficult for Sedra to manoeuvre her wheelchair across the stones left by the collapsed buildings, but she is resilient.

She beams as we talk about the princess-covered schoolbag stuffed with books next to her in the chair. But when she remembers the quake, her face is different, still filled with fear.

"I'm scared of another earthquake," she says.

Scars of war

Syria's children know trauma all too acutely.

The country was already suffering badly from the effects of 12 years of war.

More than 7,000 people died in February's devastating quake and for those who survived the situation is now even tougher.

According to the UN, more than four million people in north-west Syria depend on humanitarian aid, the majority of them women and children.

In each place we travelled to, earthquake survivors told me they felt forgotten and still had not received the help they badly needed.

At least 148 communities in north-west Syria have been affected by the earthquakes.

Rows of fresh graves

A few miles from Sedra's home, on the side of a hill, the sun beats down on a peaceful, tranquil spot. In the last few weeks, this cemetery has doubled in size.

Some graves are older, almost hidden from view by tall grasses and purple flowers. But row upon row of them are fresh, marked out by white breezeblocks on the neatly-dug brown earth.

Birds sing in the ancient olive trees and the view into the valley is a beautiful panorama of green trees and fields all the way to the edge of Syria and the mountains that mark the Turkish border.

Ali Sheikh Hazem Ghannam walks slowly through the cemetery. Some 61 members of his family are buried here.

"Everyone was sleeping and we felt the earthquake strongly," Hazem says. "The sound was very loud and the building was shaking left and right."

"We went down into the street, multiple buildings just collapsed. It was like a minor apocalypse, we spent days unable to process what had happened."

Many of the victims were only children, crushed when the upper floors of their buildings crashed down upon them as they slept.

As Hazem walks through the rows of graves, he gestures. "Here we have Adil Ghannam, his wife, and his kids, and we have Allam Ghannam, his wife and kids. Ayman Ghannam and his family are over there, they are my cousins."

More than 10,500 buildings across north-west Syria were fully or partially destroyed by the tremor.

Hazem takes us to meet the family members who survived. One of them, Nada, lies in bed inside the tent her family now sleeps in, an intravenous drip hanging from the canvas wall.

After the men leave, she and her mother carefully lift the bedclothes to show me her injuries. Her pelvis and legs were crushed, and white surgical dressings swathe her hips. The pain is constant.

In the damaged home which still stands next door, her children are lying on the sofa, carefully resting their wounded legs. Mustafa and Mohamed quietly watch television.

Hospitals overwhelmed

In other countries, Nada and her children would still be in hospital, in a clean ward surrounded by medical staff. But that level of resource just does not exist here.

Hospitals in rebel-held Idlib province have been overwhelmed for years, and there is only space for the most serious cases to stay and recover.

"We have already been suffering from the war and everything that the criminal Bashar al-Assad has done to us," Hazem says. "From shelling and displacement to siege.

"Then this earthquake came and increased our suffering even more. We had hope in the past that we would overcome the injustice, but now our hope has turned to pain."

The situation in Syria is one of the world's worst humanitarian crises.

In the days after the earthquake, even as countries geared up to respond, aid was slow to reach Syria.

New tents and medical supplies were desperately needed as well as earth-moving equipment and specialised teams to look for survivors in the ruins. Those who live here say the delay cost lives.

As we speed along the winding roads, we spot a scene of destruction near the crest of a hill. Diggers tear through the smashed concrete and twisted metal, sending clouds of dust into the air.

Around 300 people died when this single building collapsed. Weeks after the quake, it is impossible to say whether every lifeless body has been recovered from underneath the rubble.

Here in Syria, the process is slow. There simply is not enough heavy machinery for every town and village to clear away the debris quickly.

Lack of shelter

Across Idlib, the destruction wrought by conflict merges into the damage caused by the earthquake.

The scars of a long war are everywhere and they have made people resilient. Homemade shelters that fell apart during the earthquake have been patched back together.

A bustling market has been set up right on the edge of a yawning hole where another multi-storey building fell to the ground and was cleared away.

People browse an open-air rail of clothes and a woman spreads out a blanket picked from a bundle laid out on the road.

When the quake came, it hit these already-struggling communities hard. Many already lacked safe shelter, like Um Soliman and her extended family of children and grandchildren.

Their home had already been half-destroyed in an airstrike. The upper floors have been scythed away from the rest of the building, walls and floors are missing, doors open onto nothingness, just a long drop to the ground below.

"Since the war started, we have not had one good day," Um Soliman tells me, "and then the earthquake happened and it made us more scared. When the aircraft used to shell us we prayed to Allah, but now this came from Allah."

When the earthquake shook this house, they were terrified, knowing that it did not provide the protection they needed.

More chunks of masonry crumbled away as the family ran outside. They were lucky to survive. Despite it all, it is still their only real source of shelter.

'We're scared of everything'

They are too scared to sleep in here, but during the day it is still the place where they cook and gather. Pulling back the curtain that divides the hallway from the outdoors reveals a tiny baby sleeping peacefully at the foot of the cracked walls.

The family are warm and welcoming, desperate to show the reality of their living situation but painfully aware that it is dangerous for any of us to be inside the precarious building.

Any thoughts of reconstruction are still far away. In neighbouring Turkey, an ambitious rebuilding programme has become a pre-election campaign.

In Syria though, for now, clearing the debris of collapsed buildings is the best most people can manage. Creating new ones would need materials that are already in short supply.

In Um Soliman's house, the children play carefully. They try to avoid the cracked walls and the constant fear in the eyes of the adults.

"We are scared of everything, but where will we go," she asks, taking my hand in hers.

"We have set up a tent outside, and when things get worse here we will move to it. The kids are always crying and their screams are everywhere. What can we do? We pray this never happens to anyone else."