Syria Earthquake: Why did the UN aid take so long to arrive?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UN's delay in delivering life-saving aid to Syrian victims of last month's devastating earthquake was unnecessary, legal experts have told the BBC.

They said the UN did not need to wait for permission to enter from the Syrian government or the Security Council and could have applied a broader interpretation of international law.

It took a week before the UN got approval from Syria's president to open extra border crossings to allow access to the opposition-held north-west.

The UN itself has said it is crucial to try and rescue quake victims within 72 hours. It disputes the BBC's findings that it could have acted differently.

"What matters in terms of responding to an earthquake is time and the immediacy of the response. And the UN just stood there completely paralysed," international human rights lawyer, Sarah Kayyali, told the BBC.

More than 4,500 people were killed and more than 8,700 injured in north-west Syria by the earthquake, the UN says.

Centred near Gaziantep in Turkey, the 6 February 7.8 magnitude tremor and subsequent earthquakes and aftershocks killed at least 45,968 people in Turkey, according to officials there, and about 6,000 in Syria as a whole.

Andrew Gilmour was a senior UN official when the first resolution on delivering aid to rebel-held territories to Syria was negotiated in 2014.

His opinion is that cross-border aid is legally permitted.

"If a UN lawyer tries to interpret it as meaning you somehow can't provide milk powder to a starving baby, then he is making an obscene and illegitimate farce of international law," he says.

The BBC has spoken to more than a dozen experts in total, including eminent lawyers, professors, retired judges of the International Court of Justice and former UN legal officials. All said that deaths could have been prevented, if the UN had used a different interpretation of international law to allow it to respond in north-west Syria.

UN spokesperson Stéphane Dujarric told the BBC that: "To deliver humanitarian aid across an international border, we need either the consent of the government, or in the case that we have in Syria, a binding Security Council resolution... we can have academic discussions for weeks, months, and years about international law. Our position is that international law has not delayed our work."

In addition to delivering aid itself, the UN also plays a vital role in co-ordinating international relief efforts offered by other countries after a natural disaster. It arranges search and rescue through United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination (Undac). Undac teams can deploy anywhere in the world within 12 to 48 hours of a request, which is what happened in Turkey.

But the UN made no formal request for emergency medical teams to enter north-west Syria, and was not able to tell us about any formal request for search and rescue teams to deploy there. International humanitarian specialists working on the response have told the BBC that without that call from the UN there was no clear way for emergency teams to deploy.

The UN's Stéphane Dujarric says the lack of emergency teams is down to national government decision-making. "There are security concerns. There are all sorts of political concerns" which may have influenced this, he says.

Marco Sassoli, special advisor to the prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, said that the Geneva Conventions - the basis of international humanitarian law - provides a framework for the UN to deliver aid without the need for Syria's permission.

"The Geneva Conventions, to which Syria is a party, has a provision stating that an impartial humanitarian body… may offer its services" to all sides of a conflict, he told the BBC.

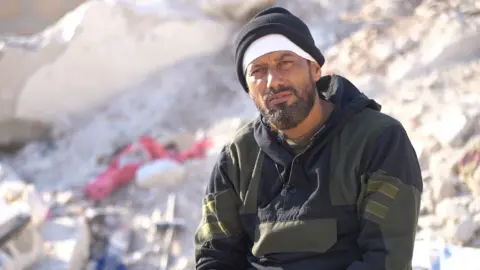

Victims of the earthquake have complained about the UN's response.

Omar Hajji lost his wife and five children to the disaster.

He spoke to the BBC in the days following the quake as he looked for his remaining missing son, 14-year-old Abduhrahman. He was finally reunited with him after three days of searching.

"UN aid wasn't sufficient," Omar says, who spent days digging through rubble looking for friends and family with his bare hands. "The most significant aid we received was from locals… If the UN aid had arrived earlier things would've been very different."

One week after the quake, Martin Griffiths, the UN's head of emergency relief, visited the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. The UN has "so far failed the people of north-west Syria", he wrote on Twitter. "They rightly feel abandoned. Looking for international help that hasn't arrived."

This story has been amended to clarify a quote.