Israel and Lebanon gas field talks on knife-edge

Reuters

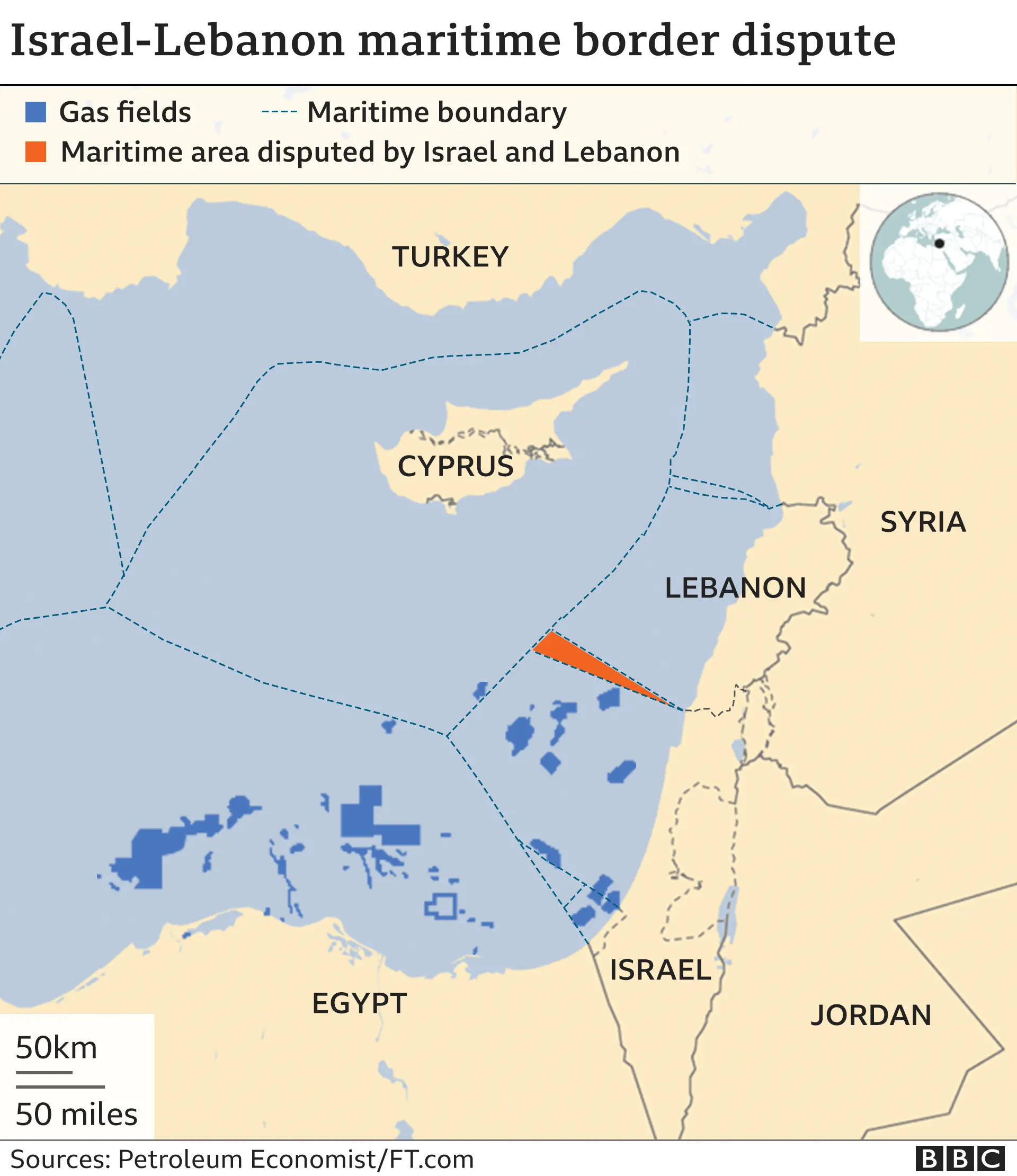

ReutersAs Europe frets over gas prices, Israel and Lebanon have reached a vital stage in indirect talks over natural gas fields in disputed offshore territory.

The neighbours, which see each other as enemy states, are reportedly closer than ever to reaching a deal.

If they play their cards right, there is the prize of tapping new and potential energy resources.

But a misstep could result in war, with the Lebanese militant group and party Hezbollah making new threats to Israel.

A triangle of turquoise Mediterranean waters is at the heart of the row over competing energy exploration rights. It contains part of the Karish gas field and part of Qana, a prospective gas field.

Israel maintains that Karish - licensed to London-listed company Energean - lies fully within its internationally recognised economic waters. Historically, Karish fell outside Lebanon's claimed boundary, but in recent years it has argued that the gas field falls partly within its territory.

In July, after an Energean production and storage vessel was sent to float above Karish, Hezbollah flew three unarmed reconnaissance drones towards it. They were shot down by the Israeli military.

Preliminary work for gas extraction is now due to start - an Israeli move that Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has called a "red line".

In response, Israel's Defence Minister Benny Gantz warned Mr Nasrallah that for any attack "the price will be Lebanon".

Quid pro quo

Production from Karish - though a relatively small field - is part of Israel's plan to export gas to the European Union, as the bloc seeks alternatives to Russian energy. Israel aims to supply 10% of what Russia provided before its invasion of Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Lebanon - crippled by severe power shortages amid an economic crisis - desperately hopes to find significant gas deposits at Qana, which extends into the disputed zone. These could then be used in years to come for domestic energy and foreign exports.

"Lebanese politicians view this as the potential road to economic recovery," observes David Wood, senior analyst for Lebanon at the International Crisis Group (ICG).

On Monday, the office of Lebanese President Michel Aoun tweeted that he "expects a written offer... concerning the demarcation of a maritime border with Israel by the end of the week".

If so, that would mark a very important step in shuttle diplomacy by the American mediator Amos Hochstein.

An official in Washington told the BBC that Mr Hochstein was continuing his "robust engagement to bring the maritime boundary discussions to a close".

"We continue to narrow the gaps between the parties, and we believe a lasting compromise is possible," the official said.

While no details have been formally released, it has been reported that the offer involves Lebanon moving its boundary claim back from the northern part of Karish and in return being allowed to take control of Qana.

It is possible that Israel may ask for a share of future profits from Qana, if gas exploitation proves viable, or for territorial compensation.

Another sensitive point in negotiations concerns the question of whether agreement on a maritime border would have any implications for sovereignty along a stretch of shared coastline and further inland.

Political calculations

For leaders on both sides, keen to show a win for their countries, the clock is ticking.

Michel Aoun is due to leave office on 31 October and Israel's Prime Minister, Yair Lapid, faces a parliamentary election on 1 November.

"For Israel, a deal on the maritime border is really about solving a security and strategic threat," argues Orna Mizrahi, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies, based in Tel Aviv.

AFP

AFPShe stresses how a deal could defuse a potential source of conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, which is heavily armed and backed by Iran, but says there is great caution in the military establishment.

Israel and Lebanon have a history of bloody wars. Israel invaded Lebanon during the latter's civil war in 1982. In 2006, a cross-border raid by Hezbollah triggered a month of fighting.

"The IDF has been on a high alert for months and is ready for every scenario of deterioration," Ms Mizrahi says. "Maybe Nasrallah could do something not against the rig but along the border."

"Maybe he would like a contained military conflict that would serve him because he needs to be seen as the defender of Lebanon, to justify why Lebanon needs this very strong independent militia."

Indirect negotiations between Israel and Lebanon first began a decade ago, with the discovery of valuable deposits of offshore natural gas.

But previous US-led efforts to solve their differences failed.

This time, analysts believe a deal, described as "unthinkable, just months ago" by David Wood at ICG, could now be in reach.

Mr Wood says an extra motivation for Israeli officials is the belief "that Israeli security interests are best served by Lebanon's economy being rebuilt rather than the crisis getting worse".

Another "political gain", he adds, would be "to show that Lebanon and Israel can resolve disputes amicably or diplomatically through negotiation rather than resorting to violence".

In turbulent times, that could make encouraging news for US and European leaders as well as potential investors.