Tough tests for Joe Biden in 'new' Middle East

Reuters

Reuters"Folks, it's a time of testing." So said America's new president in Wednesday's inauguration speech before listing the tests the country faces and concluding with "America's role in the world".

Some of the toughest questions on that exam are in the Middle East.

Joe Biden's team is dominated by old hands from the Obama administration returning to a region with new orders to revisit old issues.

Their biggest challenges involve policies they personally helped to shape - in places in far worse shape now. But some see openings and opportunities in that.

Reuters

Reuters"They've learned from what went wrong with the Obama administration's approach to the Middle East," observes Kim Ghattas, a non-resident fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and author of the book, Black Wave, on Saudi-Iranian rivalry in the region. "They may take things in a different direction because they've learned from the mistakes, and because the region today is a very different place."

In the top tray of the new administration's foreign files is policy towards Iran. The landmark 2015 nuclear deal by world powers is now dangling by a thread after Donald Trump discarded it and despatched waves of crushing sanctions. There is also the devastating war in Yemen, which Mr Obama initially supported, partly to assuage Saudi anger over the accord with its arch-enemy Iran.

Reuters

ReutersPresident Trump's term kicked off with the unorthodox choice of Riyadh as his first foreign stop in May 2017, where he signed a $110bn (£80bn) arms deal - the biggest in US history. It set in motion a Middle East policy anchored in unswerving loyalty to the kingdom and "maximum pressure" on Iran. That paved the way for a new axis of emboldened Arab states in the Gulf and Israel.

"Active diplomacy by some of the old hands that served under Obama may be just what the region needs," says Hassan Hassan, editor of Newlines magazine, a new publication focusing on the region.

"Arab states believed they could redraw the political map of the region in the absence of American leadership. But, after half a decade of trying, they recently recognised their limits in places like Libya, Yemen, Iran, and even against a tiny neighbour like Qatar."

Reuters

ReutersAn emphasis on re-engaging with old traditional allies is already at the top of the new team's talking points.

"It's vitally important that we engage on the take-off, not the landing, with our allies and partners in the region, to include Israel and the Gulf countries," pledged Antony Blinken, the nominee for secretary of state, during a Senate confirmation hearing which lasted more than four hours and often focused on Iran.

Mr Blinken, a long-time senior aide to both Mr Biden and Mr Obama, emphasised that a new agreement could address Iran's "destabilising activities" in the region as well as its development of ballistic missile - two additional concerns also shared by many Western capitals. However, the Biden team will not want to ditch the 2015 agreement regarded as a rare success story of multilateral diplomacy.

EPA

EPA"If you look at the Biden appointees for foreign policy, nuclear disarmament and treasury positions, so many had a direct hand in the nuclear talks or the implementation of the deal," notes Ellie Geranmayeh, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

"The Biden camp and Iranian leaders seem to be overlapping on one thing - the need to bring all sides back into full compliance with the nuclear deal - and they'll need to move swiftly to discuss how to sequence this," she emphasises. The appointment a US special envoy is on the cards.

Ever since Washington pulled out, Tehran has been inching away from its commitments regarding limits on its nuclear programme. Its recent announcement that it had resumed enriching uranium to 20% purity - far beyond limits set out in an accord meant to prevent it from acquiring nuclear weapons - ratcheted up tensions with the US as well as European powers.

Iranian leaders have repeatedly underscored that they will return to their obligations under the deal once the US does the same. But the vagaries of the last four years have also hardened suspicion at home of engaging with the West.

EPA

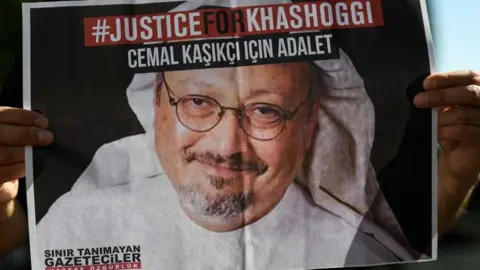

EPAThe new US administration will also face a reckoning at home too. A newly elected US Congress, with many foreign policy veterans, is already signalling that it wants a greater say. In the Middle East that will mean everything from any deals with Iran; an end to US military support enabling the Saudi war in Yemen; Israeli-Arab peacemaking; to concerns over Saudi Arabia's human rights policy, including the detention of dissidents and the stubborn stain of the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Mr Biden's Director of National Intelligence, Avril Haines, was asked in her confirmation hearing if she would end the "lawlessness" of the Trump administration and submit to Congress an unclassified report on Khashoggi's murder by Saudi agents in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018.

She replied: "Yes, senator, absolutely. We will follow the law."

AFP

AFPMedia reports, based on intelligence sources, have said the CIA established a "medium to high degree of confidence" that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman must have ordered the killing. He has repeatedly denied this.

"The Americans will have to give him the benefit of the doubt, because there is no smoking gun," insists Ali Shihabi, a Saudi author and analyst. "Whether it's the CIA or the state department, or the Pentagon, the reality is a fundamental understanding that Saudi Arabia is absolutely crucial for them to be able to do anything in the region."

There are many shared priorities, including ending the disastrous war in Yemen. But like most files in this region, there are no easy options.

"It isn't as simple as ending military support for Saudi Arabia," cautions Peter Salisbury, the senior Yemen analyst with the International Crisis Group. "If the US wants peace there, it is going to have to become much more active as a diplomatic player."

Reuters

ReutersDiplomacy will involve many awkward exchanges, especially for an administration which has already put human rights on their agenda. That will mean difficult conversations everywhere from Riyadh to Tehran and Cairo and beyond. Many will watch - with anxiety or anticipation - to see if talk translates into action.

But for all the new approaches, they will also build on the old. There is praise for the Trump team's Abraham Accords, the agreements that established full diplomatic relations between several Arab states and Israel. But Mr Blinken has indicated they would "take a hard look" at some of the commitments they entail. They range from arms deals with the United Arab Emirates to US recognition of Morocco's claim of sovereignty over the disputed region of Western Sahara.

Unfinished business and unending crises in Iraq and Syria and Israel-Palestinian peacemaking; new challenges in Lebanon; and the enduring threat of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) group - the list is long for an administration which has its own fires at home.

"I think there is definitely a moment of opportunity," says Kim Ghattas. "It's going to be very difficult. But there is a moment of opportunity to rethink America's role in the world and to rethink the Middle East."