Colombia ex-fighters brew up new lives after giving up guns

ProColombia

ProColombia"Tropics - Fruits of Hope" is the inspirational name former rebels in Colombia have chosen for their new venture.

A premium coffee, "Fruits of Hope" is grown, harvested and roasted by more than 1,000 guerrilla fighters who laid down their arms following the signing of a peace agreement between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) and the government in 2016.

Last week, a former rebel came to London to promote "Fruits of Hope" - a special edition marking the fifth anniversary of the peace agreement - at the annual London Coffee Festival.

The combatants-turned-coffee growers hope their latest product will be as successful as their "Spirit of Peace Ex Combatants", which was named "Best of the Best" at the Ernesto Illy International Coffee Award in 2019.

Mesa Nacional del Cafe

Mesa Nacional del CafeThey are among almost 13,000 former Farc guerrillas who have joined the Colombian government's process of reincorporation into civilian society.

Rather than hiding their past, many make a virtue of their unusual entry into the labour market by alluding to it in the names they give their products.

One of the beers they brew is named "La Trocha", Spanish for the small paths used by the rebels to criss-cross the Colombian jungle. Clothes designed and made by one of their co-operatives were shown at the fashion show "Pazarela", a play on the Spanish words for peace (paz) and catwalk (pasarela).

ARN

ARNThe man who has travelled from the coffee-growing Cauca region to London to promote "Fruits of Hope" also does not hide his past.

"My name is Antonio Pardo," he says, automatically giving his nom de guerre.

Asked why he still uses the alias instead of his family name, he explains that he no longer associates it with the conflict in which he fought for 10 years.

"It's not a nom de guerre to me, it's a peace name now," he says, adding that most of his friends and former comrades would not recognise the name Jhon Jairo Moreno. "That's just the name on my ID and, of course, the one my family calls me."

Mr Pardo, who joined the Farc as an 18-year-old sociology student in the city of Cali, says that he and his fellow ex-combatants are 100% committed to peace now.

He says that in his rebel cell, made up of 50 fighters, everyone embraced the peace process that put an end to the decades-long conflict in which 260,000 people were killed.

"There came a point at which we recognised that the majority of people in our country wanted an end to the violence."

'Traumatic'

He adds that there were elements both on the political far right and far left who wanted the conflict to carry on, but insists that the vast majority of those in the Farc signed up to the peace deal.

Mr Pardo describes the years which followed as "traumatic".

It took much longer than expected to house those who had demobilised. And out of their jungle hideouts, the newly disarmed rebels became sitting ducks for other armed groups looking to settle old scores.

Getty Images

Getty Images"There were failures on the part of the government, failures they described as delays. But those delays could be deadly for us," he says referring to the more than 300 demobilised Farc rebels who have been killed since the 2016 signing of the peace agreement.

Mr Pardo himself became the target of an assassination attempt last October when a gunman tried to open fire at a restaurant. The former rebel was lucky, the gun jammed and the assailant fled after being confronted by one of Mr Pardo's bodyguards.

Dangerous dissidents

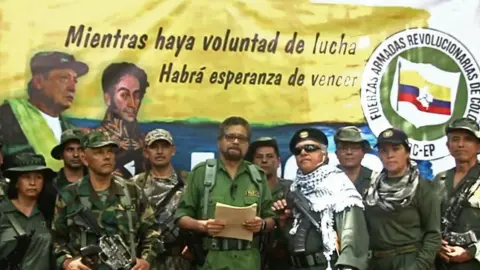

There are also Farc offshoots - groups that did not agree with the peace deal and refused to lay down arms - which continue to mount attacks in Colombia.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesColombian security sources put the number of these dissidents at 2,400 and describe them as one of the biggest dangers to the country's security.

Mr Pardo insists that while these dissident groups may be led by some former Farc members, their rank and file is mainly made up of newly recruited fighters.

And it is this facility to recruit people willing to take up arms which he sees as a continuing threat to peace in Colombia.

But he says that the work demobilised Farc members are doing in coffee co-operatives and other reincorporation projects is building trust between former rebels and the community at large.

The head of Colombia's Agency for Reincorporation and Normalisation (ARN), Andrés Felipe Stapper, says that involving local communities in the reintegration of the rebels has been key to the programme's acceptance.

He says that the idea is for locals to benefit from the projects, such as the building of housing and the paving of roads, and that in many cases they work alongside former rebels.

Often the ideas for the projects come from the ex-rebels themselves, he says.

Mr Stapper's favourite is Caguán Expeditions, which offers white-water rafting tours guided by a mixed team of locals and former guerrilla fighters on a river running through a former rebel stronghold.

ARN

ARNIn 2019, the eight guides were invited to the World Rafting Championships in Australia. The team may not have been part of the official competition but the international recognition they received did its part towards bolstering reincorporation efforts back in Colombia.

Antonio Pardo, who made the move from rebel to coffee grower, is adamant that despite the risks he and others still face it is time to put thoughts of retribution aside.

"What the country wants is for the war to stop, so there are no more victims so that we can all move forward together."