Jesús Santrich: Leader of Colombian breakaway rebel group 'killed'

Reuters

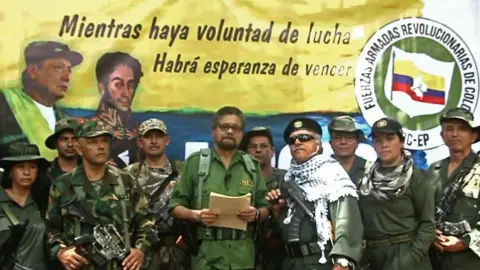

ReutersThe Colombian left-wing rebel leader known as Jesús Santrich has been killed in Venezuela, members of his group say.

Santrich was a key figure in peace negotiations but later joined a dissident group and continued fighting.

The dissidents, Second Marquetalia, said he had been killed by Colombian armed forces but offered no evidence.

Colombia's defence minister said intelligence reports suggested he had died in a shootout between gangs but stopped short of confirming his death.

What is known about what happened?

Very little is known for certain at this point. The only official statement has come from Colombian Defence Minister Diego Molano who said there had been "an alleged confrontation between criminal gangs in Venezuela" and that Santrich "and other criminals" reportedly had died in that confrontation.

Second Marquetalia said in a statement that Santrich had been travelling in a lorry inside Venezuelan territory when "the lorry carrying the commander [Santrich] was attacked with rifle fire and grenades". It blamed "Colombian commandos" for the attack.

The Venezuelan government has not commented.

Some local media are speculating whether Santrich, for whose arrest the US government offered a reward of $10m (£7m), may have been killed by mercenaries.

Others say that Santrich may have been killed by a group led by his former comrade-in-arms turned rival, Gentil Duarte.

What do we know about Jesús Santrich?

Jesús Santrich is the nom de guerre of Seuxis Pausias Hernández Solarte, a former commander in the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), a Marxist rebel group which engaged in a five-decade-long armed struggle against Colombian government forces and right-wing paramilitaries.

AFP

AFPHe joined the rebel group after a student friend of his was killed by Colombian security forces. Jesús Santrich was the name of the killed friend and it was in his honour that the philosophy student adopted it as his pseudonym.

Santrich was partially blind, having gradually lost his sight due to a genetic condition.

He was a member of the Farc rebel group for 30 years and one of their most hard-line negotiators in the process which led to a peace deal in 2016.

From peacemaker to dissident

Santrich was one of 10 former Farc rebels who in 2018 were given seats in Colombia's Congress under the terms of the peace deal.

But before he could take up his seat, a grand jury in the United States accused him of conspiring to smuggle 10 tonnes of cocaine to the US.

A legal saga followed which saw him arrested, released, re-arrested and eventually released again.

In June 2019, he was finally sworn in as a lawmaker in the Colombian House of Representatives, but weeks later he disappeared from where he was staying, near the border with Venezuela.

He re-appeared two months later in a video broadcast on YouTube in which he stood next to fellow ex-Farc rebel leader Iván Márquez while the latter called on their followers to take up arms again.

AFP

AFPIván Márquez accused the Colombian government of "betraying" the peace agreement with the Farc and announced a "new phase in the armed conflict".

He and Santrich became the leaders of a dissident group calling itself Second Marquetalia, after the town in which the Farc were originally founded in the 1960s.

It is not clear where the video was recorded but the Colombian government has long accused neighbouring Venezuela of harbouring breakaway factions of the Farc.

Where does this leave the peace process?

Until it is known what exactly happened, it is hard to predict what the long-term effects might be.

The situation at the Colombia-Venezuela border is already volatile, with a number of armed gangs operating in the region.

Tension has further risen in recent weeks after clashes between Venezuelan soldiers and armed groups in the Venezuelan state of Apure, sending thousands of Venezuelans fleeing across the river to Colombia.

A group claiming to be a breakaway faction of the Farc recently released a video of eight Venezuelan soldiers it is holding. The situation is further complicated by the fact that Venezuela and Colombia do not have diplomatic relations.

However, it is important to note that while there are a considerable number of Farc rebels who refused to lay down arms, a majority did.

Those former Farc commanders who have stuck with the peace deal have since created a political party, Comunes, and last year issued an apology for the kidnappings they carried out during their time as rebels.

Neverthless, armed attacks continue to be a problem, with rights defenders, Afro-Colombians, indigenous Colombians and former Farc rebels among those most often targeted.