Why confidence in Argentina's economy is dwindling

AFP

AFPWhen a business-friendly conservative was elected president of Argentina in October 2015, hopes were high he would put the South American country's economy on a stable path.

Mauricio Macri promised to revive Argentina's economy and achieve "zero poverty". But less than three years later, he has unexpectedly asked for the early release of a loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). What has gone wrong?

What's the latest?

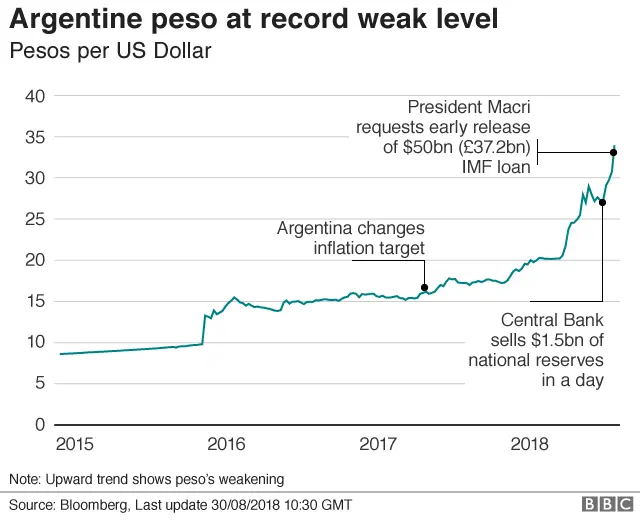

The Argentine peso has lost more than 40% of its value against the US dollar this year and inflation is rampant. Everyday life is getting more expensive for Argentines, as the prices of many goods and services still bear a close relation to the US dollar.

The government of President Macri has not been able to lower inflation, which is the highest amongst G20 nations. It is failing to enact the economic reforms it promised the IMF, most of them aimed at curbing public spending and borrowing.

And the combination of spiralling inflation and public spending cuts means wages are not keeping pace with prices, making most people poorer.

How did the crisis start?

Argentina has been plagued by economic problems for years but the commodities boom of the past decades helped the country repay the money it owed the IMF. It cleared its entire debt to the multilateral organisation in 2007.

EPA

EPAArgentina's economy began to stabilise under President Néstor Kirchner, who governed from 2003 to 2007, but became more shaky again under his wife and successor in office, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

Her government, which was in power from 2007 until 2015, raised public spending, nationalised companies and heavily subsidised many items of daily life ranging from utilities to football transmissions on television.

Most importantly it controlled the exchange rate, which created all sorts of practical problems, such as giving rise to a black market for dollars and heavily distorting prices.

What did President Macri promise to do?

Mr Macri was elected on a promise of ending all distortions and returning Argentina to a market-oriented economy where supply and demand, not the state, would define prices.

In his first hours in office he put an end to capital controls and began a global campaign to repair Argentina's reputation with foreign investors.

He also promised to bring down inflation, which was hovering around 40% per year, by curbing public spending.

Can the IMF help?

Argentina's government insists its problem lies with liquidity (a lack of cash) and not with solvency (its ability to meet its financial obligations).

In May, it turned to the IMF for help, arguing that the Washington-based fund was the cheapest source of financing available.

EPA

EPAThe argument went that with a loan from the IMF, Argentina would be able to intervene in currency markets for longer and also pay off bonds coming up for payment.

At the time, President Macri said he did not plan to use the $50bn (£37.2bn) loan from the IMF except to boost the country's reserves.

But with the peso sliding further and hit by a poor soybean and maize harvest, the economy continued to deteriorate. In June, the economy fell by 6.7%, its worst downturn since 2009.

With confidence in Argentina's recovery eroded, President Macri on 29 August unexpectedly asked for the early release of the IMF loan.

IMF chief Christine Lagarde said the fund was ready to help Argentina but news of the request for early assistance caused the peso to drop more than 7%, its biggest one-day decline since the currency was floated.

What do Argentines think of all this?

AFP

AFPGoing to the IMF is the most unpopular move a president could make in Argentina, where the organisation is widely loathed and blamed for the 2001 economic collapse.

In general, Argentines are not quick to panic, having been through so much economic turmoil in the past.

But there are people expressing serious concern, especially those from the older generation which lived through Argentina's 2001 economic crisis when the government defaulted on its debt and the banking system was largely paralysed.

The effect on Argentines was devastating with many seeing their hard-won prosperity quickly disappearing.

Those who experienced it fear a return of the corralito (ring fence), the Spanish name given to government restrictions imposed in 2001 to prevent a bank run.

Under the corralito's constraints, which lasted for a year, people could not freely withdraw money from their accounts, making life very difficult for ordinary Argentines.