Channel smugglers step up risks to outfox France and UK

BBC

BBCAfter 27 people drowned attempting to cross the English Channel on Wednesday, the UK and France agreed to crack down on the people traffickers and gangs putting people's lives at risk.

Last month, the BBC's Lucy Williamson joined a French police patrol and asked - why are the smugglers so hard to stop?

It took little more than a week for Hamid to find a people-smuggler in Calais.

The networks run a slick and organised operation in the migrant camps here. Hamid got the fast-track service: within a couple of days, he found himself hiding near the beach with 75 other people, waiting to cross the Channel in a small inflatable boat.

The strip of sea that separates Britain and France is tantalisingly narrow. At dawn, struck by the morning sun, the Dover cliffs gleam like a luminous streak of pearl above the water.

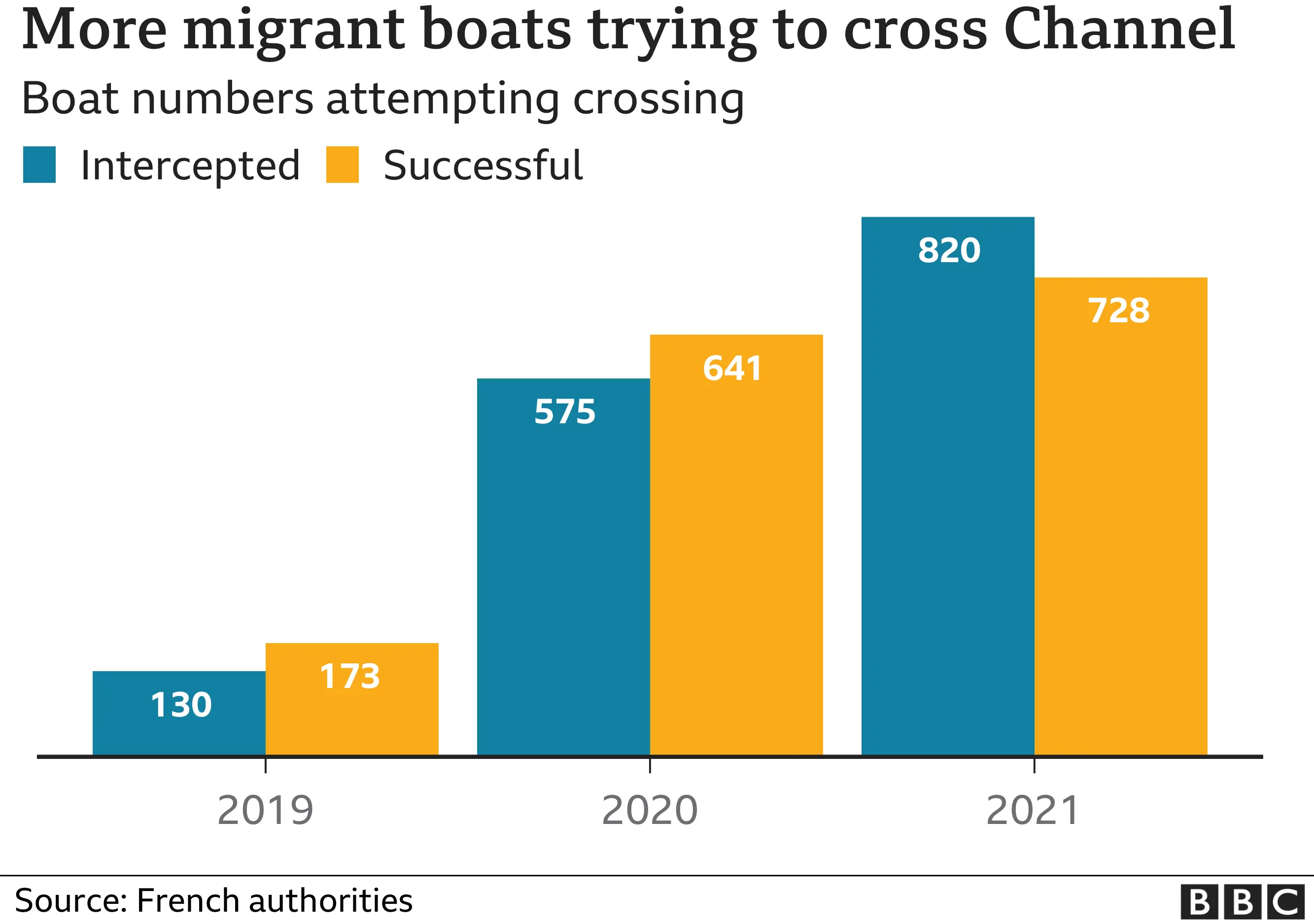

More than 18,000 people have crossed clandestinely to UK shores in small boats so far this year. Despite significant investment on both sides of the Channel, that's more than double the number that crossed last year.

So why is it so difficult for two of the world's richest and most powerful nations to stop migrants crossing 20 miles (32km) of sea?

Part of the answer is geography.

France's northern coastline is covered with dunes, foliage and hundreds of bunkers left over from World War Two - all handy places for migrants to hide.

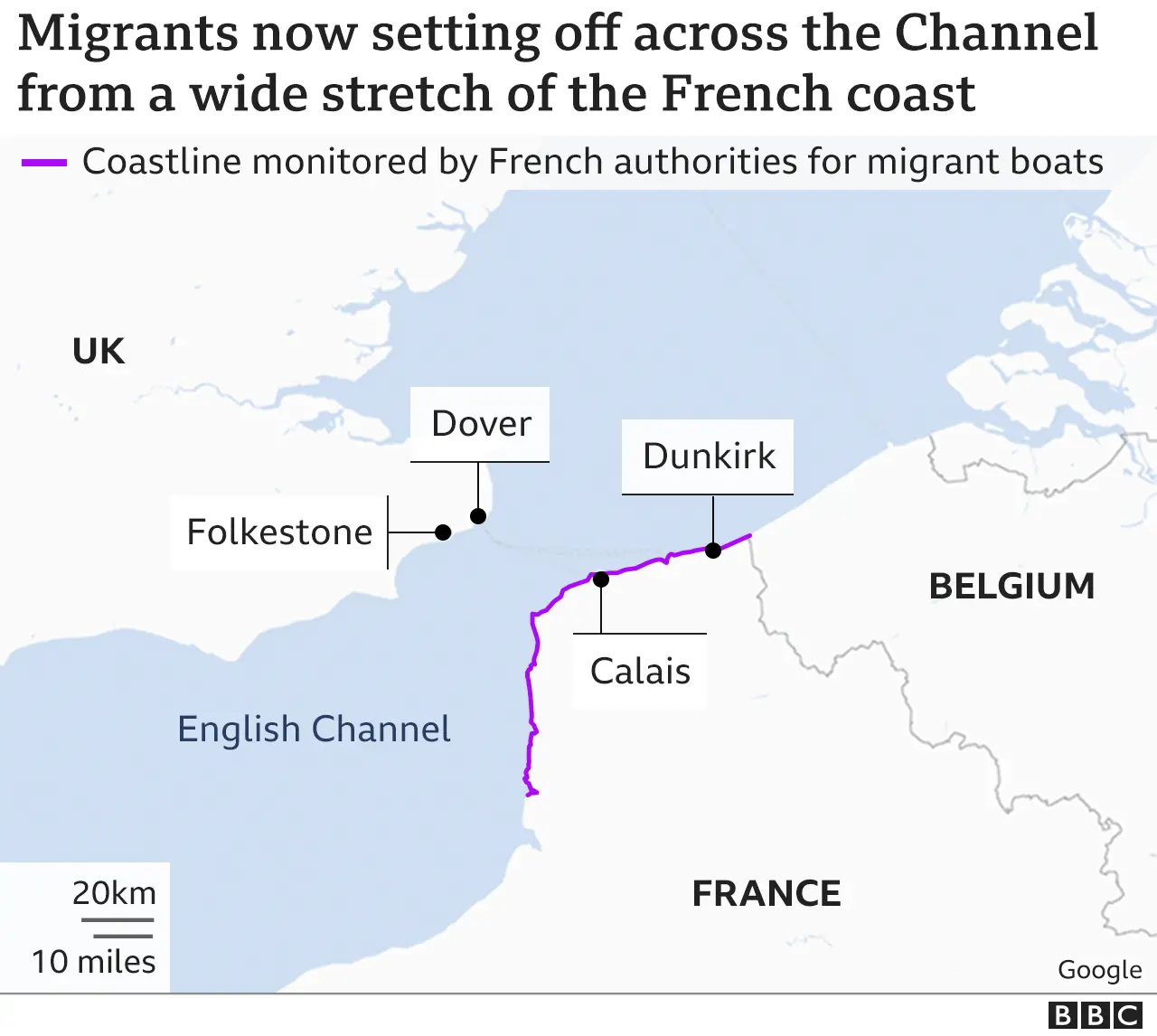

And, as patrols by police and gendarmes have intensified around Calais and Dunkirk, the smugglers have moved to riskier crossings further along the coast - as far north as the Belgian border, or as far south as the River Somme.

'Game of chess'

Gen Frantz Tavart, the gendarmes' regional commander here, says it's proof that the patrols are working. But, he told me, "it's creating a vicious cycle".

"If we divert the smugglers from the most practical route, we push them to extend their operations," he said, "and that dilutes our resources across the territory. It's like a game of chess, where the smugglers always make the first move."

Gen Tavart has 40 active gendarmes dedicated to this mission at any one time.

The UK government pays for another 90 reservists. It has promised to double that number this year - part of a £54m ($75m) funding package to boost security along the coast.

High-security fencing and surveillance cameras, paid for by the British, have been very successful in protecting the ports and Eurotunnel terminal in the past few years. But surveillance is much harder among forested dunes, and you can't put a wall around France.

One migrant, who has sometimes worked for the smuggling networks, told me that in the days before a crossing, the gangs put several security guys in position along the coast.

"They write down the timing of the police patrols," he explained. "When they change cars, when they change shifts, when they go up and down the road… it's all written down and handed to the smugglers."

Bigger boats and bigger groups

Hamid told me he was taken some distance along the coast for his crossing - I won't say where, and Hamid is not his real name. Smugglers routinely threaten migrants who talk to the media. The price of his crossing was almost $3,500 (£2,500). That's on top of the $10,000 he paid to leave Afghanistan and travel across Europe to France.

He told me he was hidden near the departure point, with 75 other passengers from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Bigger boats, with bigger groups of passengers, are another way smugglers are adapting, and Gen Tavart says it's causing fresh problems for police.

"One of the problems we have is confronting groups of 70, 80, 90 migrants who become very aggressive," he told me. "Two or three gendarmes against 20 migrants is manageable; but if you have three gendarmes facing 90 people, it's much trickier."

He admits it's sometimes "too dangerous" to intervene.

Hamid's story ends well for the police. As he and his fellow migrant passengers dragged their boat to sea, he says, large numbers of officers appeared on the beach and stopped the crossing. But he also reported that some officers told the migrants to go back to their camp and try again another day.

Increased pressure from UK

After many failed attempts, some migrants choose to settle in France. But it's in smugglers' interests to keep pushing their clients to move on. And those living in desperate conditions are easy prey for dreams. In the camps here, Britain is seen and sold as a land of ease and plenty, where housing will be provided, family welcomed, and jobs easy to get.

France now says it's stopping more than half of all crossing attempts, but some local journalists report seeing French National Police stand and watch as migrants leave. The UK has been urging France to do more, and has focused much of its own effort on tackling the problem further up the line.

The National Crime Agency has reported 65 convictions related to small boat crossings since last year, and a new joint co-ordination centre near Calais has meant better sharing of British and French intelligence.

Some say expanding that co-operation to include joint police patrols on land and sea is the only way to break the smugglers' business model in northern France. The UK's clandestine channel threat commander, Dan O'Mahoney, says it's something the UK has offered many times to the French.

"It's not something they feel they need or would find helpful, but the offer is always there," he told me. "We'd love to do joint patrols at sea as well, but the French have a very strong view about sovereignty and therefore it's not an avenue they want to explore at the moment."

Sovereignty is a loaded concept after Brexit.

Visiting security forces in Calais last weekend, the French Interior Minister, Gerald Darmanin, gave me a message for the UK: "I want to say to our British friends, who chose Brexit to take back control of their political life, that it was not, I imagine, about putting British forces on French soil, as each respects the sovereignty of the other."

There's a lot of politics at play in cross-Channel relations more generally at the moment, and not a lot of love.

But without joint patrols, and with French police only authorised to intercept boats in distress, migrants must cross into UK waters before British officers can intervene.

The UK government is now looking at how, and under what circumstances, it might legally turn those boats back towards France. But the risk of a humanitarian - and a media - disaster is real, many believe, and the number of boats eligible for turning back is likely to be very small.

It's all part of what makes maritime borders difficult to police.

Smugglers know that, just as much as governments do.

Lucy Williamson's in-depth story is featured on Our World on the BBC News Channel in the UK and is also available via the BBC iPlayer.