Who rescues migrants in the Channel?

PA

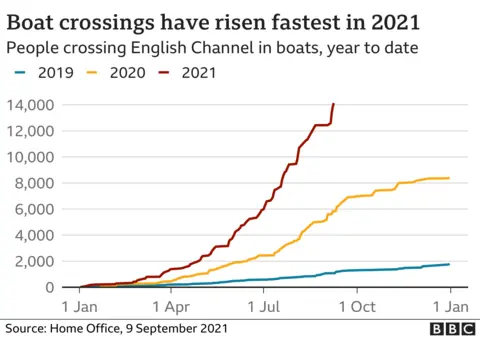

PAMore than 14,000 migrants have made it across the English Channel this year, crossing from France to the UK.

Home Secretary Priti Patel wants to allow the UK Border Force to be able to turn back boats carrying migrants across the English Channel in certain circumstances.

Can migrant boats be turned back?

It's assumed a "pushback" tactic would see UK Border Force forcing migrant vessels to turn around in the Channel. It would then be left to the French coastguard to intercept the migrant boats in their territorial waters.

UK authorities would not be allowed in France's territorial waters without consent and that could cause problems, says Prof Andrew Serdy, a law of the sea expert.

"If France doesn't want to take them back once they have left, it cannot be forced to do so and a stand-off ensues."

As well as a potential lack of co-operation with France, it's also unclear whether the UK's tactic would be legal under international law.

According to the UN Convention of the Law at Sea countries are required to "render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost".

And the practice of turning boats around came under criticism in June from Felipe González Morales - the UN's special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants:

"Pushback measures and practices demonstrate a denial of states' international obligations to protect the human rights of migrants at international borders and tarnish a state's image," he said.

In a report published in May, the UN Human Rights Council said that pushbacks were incompatible with international human rights law unless an "individualised assessment for each migrant concerned and other procedural safeguards" were in place.

That means, under international law, the UK would need to determine the risks faced by every individual migrant on a boat before forcing it out of waters, says James Turner, a barrister specialising in shipping disputes:

"There is a fundamental principle of the international law of asylum that you cannot land individuals at a place they might face persecution."

For example, in 2012 the European Court of Human Rights found Italy had broken the law when Italian authorities picked up Somali and Eritrean migrants at sea and sent them back to Libya. The court noted that the situations of migrants had not been examined individually.

Mr Turner also says the UK could also fall foul of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea because there would be "attempts to push back in some of the most dangerous and congested waters".

However, the UK government's lawyers say turning boats back would be legal in limited and specific circumstances - although they have not confirmed what these will be.

Who is responsible for migrant boats?

A country's territorial waters stretch for 12 miles off its coast. Beyond that is international waters.

That means that the most popular route between Calais and Dover (because it is the shortest) is entirely in French or British territorial water.

If a boat carrying people is found within national waters it is generally the case that that country has a duty to rescue them to a place of safety.

Who is responsible in international waters?

In international waters, it's slightly less clear and may vary on a case by case basis. But there is still a legal obligation to rescue those in distress and take them to a place of safety.

Further down the Channel, where it widens out, the waters outside of the two countries' territories are divided up into French and English search-and-rescue zones.

These rescue zones - which roughly divide the area of the Channel in half between the two countries - are co-ordinated by operations centres in Dover in the UK and Gris Nez (between Calais and Boulogne) in northern France.

It's the responsibility of the authorities there to ensure that anyone in distress in these zones receives assistance. In reality, if people are in danger, any boat nearby will have a duty to rescue them.

Those picked up in the UK zone will be taken to an English port and those in the French zone to a port in France.

Where can they seek asylum?

Under international law, people have the right to seek asylum in whichever country they arrive. There's nothing to say you must seek asylum in the first safe country.

However, under EU law there is a provision to allow asylum applications to be transferred to another member state.

The Dublin Regulation states that a person's asylum claim can be transferred to the first member state they entered.

In 2020, according to Home Office statistics, 882 people were transferred to the UK from another EU country under the Dublin rules, and 105 were transferred (from 8,502 requests) out of the UK.

Since the end of 2020, the UK has no longer been subject to the Dublin regulation because it is no longer part of the EU.

The UK grants refugee status to those who are unable to live in their own country for fear of persecution because of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or other factors such as sexual orientation. A successful application usually allows someone leave to remain for five years with the opportunity after that to apply for indefinite leave to remain.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

UPDATE - This article was first was published on 4 January 2019.