Covid: Why is EU’s vaccine rollout so slow?

EPA

EPAHas the European Commission failed EU voters in its all-for-one and one-for-all approach to procuring coronavirus vaccines? Are member countries now regretting they didn't go it alone?

As things stand, according to EU sources, the bloc looks sets to receive only a quarter of the 100 million doses it had been expecting from pharma company AstraZeneca by the end of March - putting millions of lives at risk.

Vaccine deliveries from another pharma giant, Pfizer, have also slowed down temporarily, while the firm says it's adjusting production methods.

Dwindling supplies of coronavirus vaccines have seen Madrid cancelling first dose injections for two weeks.

Regional hospitals in Paris say they're in a similar position. They said they're delaying first dose appointments in order to ensure already-vaccinated citizens their second jab.

Portugal has warned it could take up to two months longer than initially planned to complete the first phase of its vaccinations.

Angela Merkel has scheduled a Monday video conference with Germany's regional leaders and representatives of vaccine manufacturers, after her Health Minister Jens Spahn warned of "at least another 10 weeks of shortages".

Charles Michel, the president of the European Council (the man who represents EU countries in Brussels) said on Thursday he hoped delays in vaccine deliveries could be solved. If not, he said he supported the use of "all legal means and enforcement measures to ensure effective vaccine production and supply for our population".

In the meantime, the EU is trying to get some control over the number of vaccine doses leaving the bloc from pharmaceutical company sites. New powers for EU members to restrict exports of vaccines are expected to be made public later on Friday.

AstraZeneca, BioNTech and Pfizer have EU production sites. Moderna completes its vaccines for countries other than the US in Spain, although the vaccine itself is produced in Switzerland, which is not an EU member.

Basically, Brussels wants to know if pharmaceutical companies are exporting vaccines or components needed to produce vaccines from EU production sites, in order to fulfil orders elsewhere, when those same companies have delayed supplies to the EU.

Officially, Brussels insists it doesn't intend to ban vaccine exports in the future. It claims the new powers for members states are for the purpose of transparency. But the situation is evolving.

EU suspicions led it to ask Belgian investigators to inspect a factory - part of the AstraZeneca production chain - this week, to look into the company's claims that the dramatic delay in vaccine supply for the EU was due to production problems.

Brussels also asked AstraZeneca whether vaccines produced, or partially produced, in the EU were delivered to the UK. The EU has also demanded the company divert vaccines made at its UK production sites to boost the supply to the EU.

In what at first seemed an extremely emotional attack on AstraZeneca, Brussels threw at the company the fact that it had invested more than €300m (£265m; $364m) to help it develop the vaccine and to produce it in mass quantities.

In reality, Brussels has yet to hand over a substantial lump of the promised amount.

And some EU accusations just don't add up.

Take the complaint that the bloc is being treated as "second class" by AstraZeneca. The fact is, when it comes to honouring its contract with the UK, for example, the EU signed its AstraZeneca vaccine contract three months later than Prime Minister Boris Johnson's government.

AstraZeneca has also claimed that it has a "best effort" agreement with the EU, rather than a 100% commitment that the desired amount of vaccines would be delivered by the end of March.

The UK has tried to stay out of the Astra Zeneca row, with the government focusing instead on the content of their contract with the pharmaceutical company. There have been public assurances from cabinet ministers that the UK supply agreed with AstraZeneca will not be affected. That was the really important thing, said UK cabinet office minister, Michael Gove, on Thursday, also adding: "We will want to talk to and with our friends in Europe to see how we can help."

Some EU figures bridled at comments by Mr Johnson this week that he didn't want to see restrictions on vaccines or their ingredients across borders.

They took it as criticism of the discussion in EU circles - originally championed, but later stepped away from, by Germany - of a possible export ban.

Post-Brexit, relations are sensitive between the EU and UK - but by Thursday the European Commission was keen to spell out that its beef was with the pharmaceuticals, not with Downing Street.

But while there's clearly been bad luck with vaccine supplies so far, the finger of blame has also been pointed squarely - from inside the EU - at the European Commission itself.

Brussels had hoped the EU's vaccination procurement scheme would be a beacon of European solidarity and strength. A stark contrast to the "each country for itself" impression given off by member states at the start of the pandemic, when EU countries closed off national borders, and Germany and France initially blocked exports of PPE equipment, much needed elsewhere in the bloc.

A stark contrast too, according the EU, to the "vaccine nationalism'" it believed it saw in the US under President Donald Trump.

EU diplomats say the bloc was "desperate" to avoid having one EU member state pitted against the other in an "ugly" national scramble to secure vaccine contracts for their own populations.

But the Commission's ensuing three-pronged attempt to sign a number of contracts with different pharmaceutical companies, at lower prices, ensuring more legal liability on the companies themselves, undoubtedly slowed the process down.

The EU is also accused of not investing enough in expanding production capacity.

An added complication was the initial suspicion from some member states of the motives of others, such as Germany, France and the Netherlands that are homes to big vaccine producers. Were they keen for the EU to spend more on vaccine procurement, so companies on their soil could benefit?

The EU got there in the end with its contracts, amounting to 2.3bn doses, it says, but an online article from Belgium's RTBF describes the current vaccine situation as politically humiliating for the EU, especially after Brexit.

It says even though the EU managed to negotiate vaccine contracts as a bloc, even though it played a major role in the research and development of a Covid vaccine, it ultimately failed to achieve "vaccine sovereignty".

EU defenders say it's a question of perspective and that smaller, less well-off member states are still relieved the EU negotiated on their behalf as they would have probably found themselves far nearer the back of the vaccine queue had they been trying to go it alone.

EU officials also make the argument that the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has been slower to approve new vaccines in order to be extra sure of their safety.

Despite a week of rowing with AstraZeneca, for example, the EU has yet to actually approve the company's vaccine. By contrast, the UK government approved the vaccine a month ago. An EMA announcement is expected on Friday afternoon.

Diplomats point to lowering levels of vaccine scepticism amongst the EU public this year, compared with 2020, for example in France, which has a pretty high level of anti-vaxxers. They attribute that to public confidence in the EMA.

But EU vaccine problems don't just lie in Brussels.

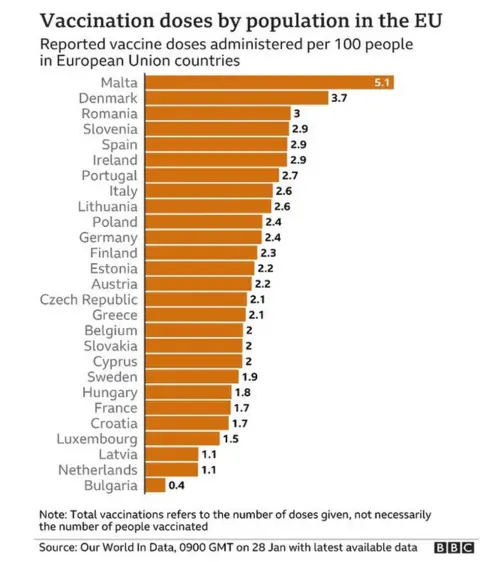

Some member countries have been far more efficient at rolling out the vaccines they have so far received, than others. Denmark is held up as a poster child, for example, whereas Germany's popular Bild newspaper has criticised Angela Merkel's government for being a "vaccination snail".

And that, coupled with a steadily climbing Covid death toll, has a definite impact on national politics - and EU solidarity.

This is election year in Germany. Under fire for the slow rate of getting vaccines into arms compared with the UK, the German government felt forced to admit it had negotiated a separate vaccine contract with Pfizer back in September.

Ms Merkel is obliged to wait with using those additional vaccines until all EU countries have received their allotted doses under the EU-Pfizer contract, but still...

Hungary, meanwhile, has agreed to purchase two million doses of Russia's Sputnik V vaccine. Since the EU has no contract with Moscow, Prime Minister Viktor Orban is legally free to start rolling out those jabs whenever he wants.

Pharmaceutical companies promised vaccine deliveries to the EU will greatly increase after March - but EU citizens look at the advanced rate of vaccinations in the UK, the US, never mind Israel, and right now the mood is fearful and sceptical.

In the initial race to find a vaccine, most countries spoke of the need for fairness.

Global pledging conferences emphasised the importance of everyone getting the vaccine, rich or poor; wherever they live.

But now vaccines are available and with Covid still a huge health threat, the rush for jabs is proving rather messier than was hoped. At least in the immediate term.

- EASY STEPS: How to keep safe

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

- CONTAINMENT: What it means to self-isolate

- HEALTH MYTHS: The fake advice you should ignore

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak