The Voice: Why Australia and New Zealand took different paths on Indigenous journey

BBC

BBCIn an Auckland art gallery this week, visitors gazed at the largest collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art ever showcased in New Zealand.

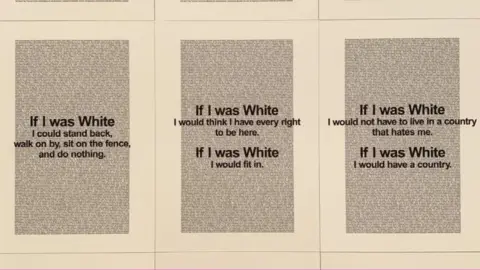

In the exhibition's final room, themed Resistance and Colonisation, observers stood back to assess a series of statements pasted on the wall by artist Vernon Ah Kee. His 2002 work, If I Was White, relays his experience as an Aboriginal Australian man in his own country:

"If I was White I could wear a suit and tie and not look suspicious. If I was White I could shop in luxury stores and not look suspicious."

"If I was White I would not have to live in a country that hates me. If I was White I would have a country."

Standing there reading the panels, Debbie May, 65, turned to her friend Wan, a 25-year-old Chinese immigrant to New Zealand, and explained that neighbouring Australia had a referendum on Indigenous people coming up, called the Voice.

"It's to give them more representation," she said. "So I think that's why this is all here," she gestured around the room. "It's connected."

More conversations like these have been taking place this year in New Zealand - another former British colony seen as closest in character to Australia - as its neighbour embarked on its landmark vote.

If passed this Saturday, the update to the constitution will recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as Australia's first inhabitants and also enshrine a small platform for Indigenous representation in politics.

But according to polling, the Voice to Parliament proposal looks set to fail - a scenario that many "across the ditch" find astonishing.

New Zealand is also grappling with a colonial history that has left its Indigenous population severely worse off. Like Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia, Māori are disadvantaged when assessed through markers such as health outcomes, household income, education levels and incarceration rates.

But in the art gallery, Ms May, expressing dismay over the likelihood of the Voice failing, suggested: "I think maybe New Zealand is a bit more forward-thinking."

"Then again," she added, "the history of New Zealand and Australia are very different, even though people might see them as similar."

Close neighbours with a difference

She's right. The countries, while alike in many ways, are actually markedly different, experts point out.

To begin with, Australia is vastly bigger than New Zealand and much more populous - with 26 million inhabitants compared with about five million. Of those populations, Indigenous Australians make up 3.5%, while Māori are a much bigger minority, representing 16.5%.

Māori culture is seen as more widely understood than the multiple Aboriginal Australian cultures too. In particular, the Māori language has seen a resurgence - New Zealand is often referred to by locals using its Māori-language name, Aotearoa.

In Australia, meanwhile, there are more than 150 distinct Indigenous languages, reflecting the sprawling diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. None of the languages has entered the mainstream and many are on the brink of extinction.

There are also differences in government structure: Australia is a federation where many powers, such as policing and healthcare, are state responsibilities; in New Zealand - much smaller and more compact - the national government holds most powers.

"Almost from the outset of colonisation, they went down very different paths," says historian Bain Attwood, an expert on British colonisation from New Zealand, now based at Monash University in Melbourne.

In New Zealand, Māori people have long been granted a political voice, guaranteed representation in parliament, says Prof Attwood.

Getty Images

Getty Images"New Zealand is looking across the ditch to Australia and I think many at least Pakeha New Zealanders [New Zealanders of European descent] are probably puzzled that what is in their eyes such a modest proposal is struggling to win sufficient votes," he says.

From 1867, Māori people were granted seats in parliament and electorates where only Māori people could contest and vote.

"Even though there are numerous similarities between the plight of Māori and Aboriginal people in the sense that both were dispossessed of their land, they were displaced, they suffered enormous depopulation, they suffered discrimination… Māori nonetheless had a place in the political system from very early on," says Prof Attwood.

"And despite the disadvantages, they never lost that political voice. That's been enormous."

In contrast to what happened in Australia, the British Crown saw New Zealand's indigenous people as sovereign and chose to negotiate with Māori leaders.

The 1840 Treaty of Waitangi is seen as the nation's founding document - even though the rights it gave Māori were not fully honoured until the 1970s, after a bitterly fought campaign by Māori activists.

Battles continue over its interpretation, but the treaty is regarded as a fundamental national contract that lays out Māori rights and recognition.

Associated legislation and institutions such as the Waitangi Tribunal - which hears cases claiming breaches of Māori rights as stated in the treaty - have reclaimed for many Māori people land title and fishing rights which have given them a degree of capital far beyond what indigenous Australian groups have.

In contrast, there is no treaty with Indigenous people in Australia, as the British Crown never recognised them as sovereign or having rights to property, title or land, says Prof Attwood.

Experts cite a range of reasons for this - including the nature of a colony first established as a convict settlement - but many also point out that the Crown viewed Indigenous Australians as a lesser race than Māori.

"A lot of what we get today in both countries are extensions of those early histories. So we still see that initial race hierarchy being played out in Australia," says Australian politics expert Dr Peter Chen from the University of Sydney.

It's also about how history is taught…

He stresses that New Zealand's treaty "has not resolved all the 'problems' of Māori people" - but it has been a tool to organise progress and to facilitate some redress of historical grievances.

"It's also been fundamentally something about not just reconciliation and representation, but about reparations," said Dr Chen, adding Australians "haven't really begun" those discussions.

"New Zealanders have been talking about a national treaty-level debate in a realistic and legislative way since the 1970s. In Australia, 50 years later, we're having a conversation about a structure that comes before a discussion of national treaty-making."

And that discussion in the past 18 months has frayed into a divisive debate, fuelled by misinformation.

The Voice proposal asks Australians to introduce an Indigenous representative group that could offer advice to lawmakers over indigenous policies.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut many polls suggest a majority of Australian voters will overwhelmingly reject the Voice.

The arguments made against it have included that the proposals will divide the country rather than unite it, create waste and inefficiency rather than reduce it, that they simply lack detail or that the Voice will be toothless and tokenistic.

Mark Kenny, a professor of politics at Australian National University, says the referendum must be seen in the context of what he describes as mainstream Australia's poor understanding of the country's brutal past.

Australian history taught in schools has been largely focused on British conquest of land and white settler achievement, rather than the impacts of colonisation on Indigenous people, he says.

Those impacts include the massacres, the cultural genocide, the policies of forced assimilation and integration which saw Aboriginal identity suppressed, Indigenous children removed from their families; policies which have led to entrenched disadvantages that continue to this day, he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCompared to New Zealand, where the settlement was "much more upfront, much more open and organised", Australia's history is one of "marginalisation" and "silencing", the academic says.

"That has allowed Australia to proceed with some very comforting myths about itself, in terms of egalitarianism, and openness and fairness and so forth," Prof Kenny says.

And in the case of a national vote like the Voice, he argues, the narrative persists.

"The atrocities that occurred to the First Peoples of this country have not been properly taken into account by mainstream Australians," says Prof Kenny.

"And therefore there's no great kind of urgency or onus to atone for them, or to reach for some sort of settlement which acknowledges that traumatic history."

To Ms May, the gallery visitor, it's that complacency which is noticeable to a greater degree, she suggests, in Australia than in New Zealand.

Artist Vernon Ah Kee's work on the wall in front of her offers his reflection on this - it also included this statement:

"If I was White I could stand back, walk on by, sit on the fence, and do nothing."

Update 13th October: A section of this article outlining the debate over Australia's Voice to Parliament proposal has been amended to more precisely summarise the points at issue.