Pakistan flood survivors battle rising tide of disease

BBC

BBC"I can't stand the sight of my baby suffering," says Noor Zadi, as she cradles 10-month-old Saeed Ahmed in her arms.

Just weeks after she lost her home in Pakistan's deadly floods, Noor is now terrified for her son.

"We are poor and we are really worried for him," she says.

As a doctor inserts a cannula into his tiny ankle, gently easing a needle into his delicate skin, he screams in pain.

Saeed is in need of an urgent blood transfusion, having contracted a severe form of malaria.

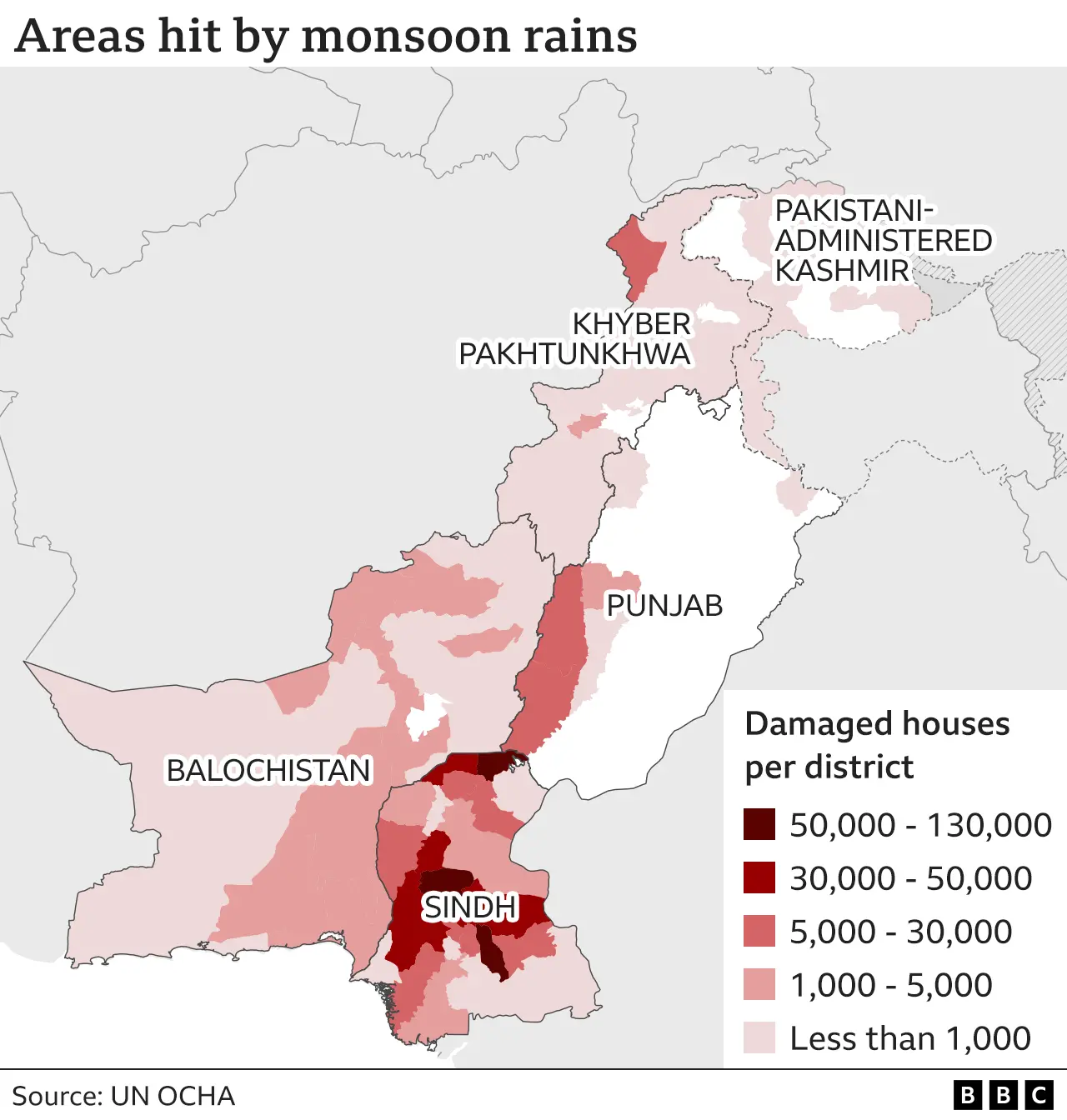

Noor's family is one of thousands now facing a double burden. Health officials here in Sindh Province - the worst-affected region - say they've seen a dramatic spike in cases of malaria, dengue and diarrhoea, as displaced families live in the open next to stagnant water.

Saeed isn't the only baby receiving life-saving treatment in the emergency ward of Thatta District hospital.

Seated on the other end of the same stretcher as Noor, another mother looks on in anguish as her child is connected to a drip.

Almost all of the patients on this ward are young children, almost all of them suffering from flood-related illnesses, says Dr Ashfaque Ahmed, the hospital's medical officer.

As he shows us around the ward, Dr Ahmed tells me he's facing an acute shortage of anti-malarial drugs.

On the adjacent bed, a woman named Shaista lies motionless on her side. Seven months pregnant, and also from a flood-impacted area, she's extremely unwell and is being transported to a bigger hospital further away, Dr Ahmed tells us.

Every few minutes another patient arrives.

As Ghulam Mustafa enters the ward, his two-year-old granddaughter Saima clings tightly to his shoulders.

"My house was completely flooded," he says, "I took her to the doctor in the camp where I'm staying but they couldn't help, so I came here."

Not everyone can get to a hospital. Half an hour away, we visit a camp in the Damdama area of the province, which has become home to hundreds of thousands of flood refugees.

As we drive towards the area, swathes of land are covered by water - the roofs of a few homes peek out from below.

Along a riverbank we pass what seems like an endless row of makeshift tents, built with the most primitive of means.

Sticks hold together pieces of cloth, or leaves, to create a flimsy structure - barely enough to provide shelter from the intense heat, let alone the rain.

Many of those living here are young families, as we approach the camp several people run up to ask us if we are doctors.

A woman carries her young son in her arms, he's had a fever for days and she doesn't know what to do.

Underneath a basic tent is where we find Rashida and four of her seven children, who are unwell.

Eight months pregnant and worried for her unborn child, she says she doesn't have money to take them to a doctor.

"They've got fever and they're throwing up… loads of mosquitoes have bitten them. My children are crying for milk," she says.

Rashida says she hasn't received any food aid, or a tent from the authorities. Others who shared similar stories say they feel abandoned.

Dr Ghazanfar Qadri, a senior government official in Thatta, admitted there was a scarcity of tents, but said food aid was being sent to as many areas as possible.

"There might be some pockets which have not been covered, but in my knowledge the entire area has been covered by rations," he told the BBC.

As Rashida awaits the birth of her next child, those words provide her with little comfort.

Officials say it could take months for the water levels to recede.

Pointing across the swollen river, she shows me where she once lived.

"Our house was washed away. We have nothing."