Pakistan floods put pressure on faltering economy

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe calls are growing louder. Pakistan desperately needs help after its worst floods in years, and it needs it fast.

"This climate calamity couldn't have come at a worse time, when Pakistan's economy was already struggling with a balance of payments crisis, rising debt, and soaring inflation," Maleeha Lodhi, former Pakistan ambassador to the UN and the UK, told the BBC.

If the country doesn't get debt relief, she added, the economy risks "tanking".

Catastrophic rain linked to climate change has submerged large parts of the country, killing nearly 1,500 people and affecting roughly 33 million people.

Homes, roads, railways, crops, livestock and livelihoods have been washed away in the extreme weather event.

With agriculture making up nearly a quarter of Pakistan's economy, officials now say the unprecedented floods may have cost up to $40bn (£35bn).

Across the country, an estimated 800,000 cattle - a key source of income for rural families - have been lost in the floods.

Farmers who have not had their crops and livestock washed away are now reportedly running low on feed for their cattle.

There will likely be more pain ahead with a food crisis looming.

Roughly 70% of the onion harvest, along with rice and corn, has been destroyed, according to Pakistan's climate change minister, Sherry Rehman.

Pakistan is the world's fourth largest rice exporter, with markets in Africa and China.

Almost all of Pakistan's households are consumers of wheat, but with so much agricultural land damaged, the wheat harvest could be at risk too.

Food prices are already under pressure because of the post-pandemic supply chain disruption and the war in Ukraine, which is a major global supplier of key crops.

Pakistan's inflation rate was more than 24% before the floods, according to reports, and some costs have climbed by 500%.

Authorities may need to import food to feed people and raw materials for industry, but the country's foreign reserves were running low even before the crisis.

Pakistan is also a producer of cotton, which is used in the country's textile industry - a major employer. Manufacturers are bracing for a shortage of that too.

On Sunday, Pakistan's finance minister Miftah Ismail said the country would "absolutely not" default on its debt payments despite the floods.

Mr Ismail also said that external financing sources had been secured, including more than $4bn (£3.5bn) from the Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and World Bank.

About $5bn of investments from Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia would be made in the current financial year, he added.

At the same time, Pakistan's central bank announced that Saudi Arabia's development authority had extended a deposit of $3bn, which had been due for repayment in December, by one year.

Also on Sunday, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said it would work with countries around the world international community to support Pakistan's relief and reconstruction efforts.

Last month, an IMF bailout package was approved but conditions were attached, like raising taxes and applying austerity measures.

Andrew Wood, an analyst at S&P Global Ratings, flagged "high inflation, a weaker currency, and tighter fiscal and monetary conditions" as affecting growth in a recent briefing. He added that the agency estimated the government's debt position was around 74% of GDP.

"Financial support from the IMF and other multilateral and bilateral partners is critical, in our view... Structural reforms that support Pakistan's business environment and macroeconomic stability would be important pillars of an enduring economic recovery," Mr Wood said.

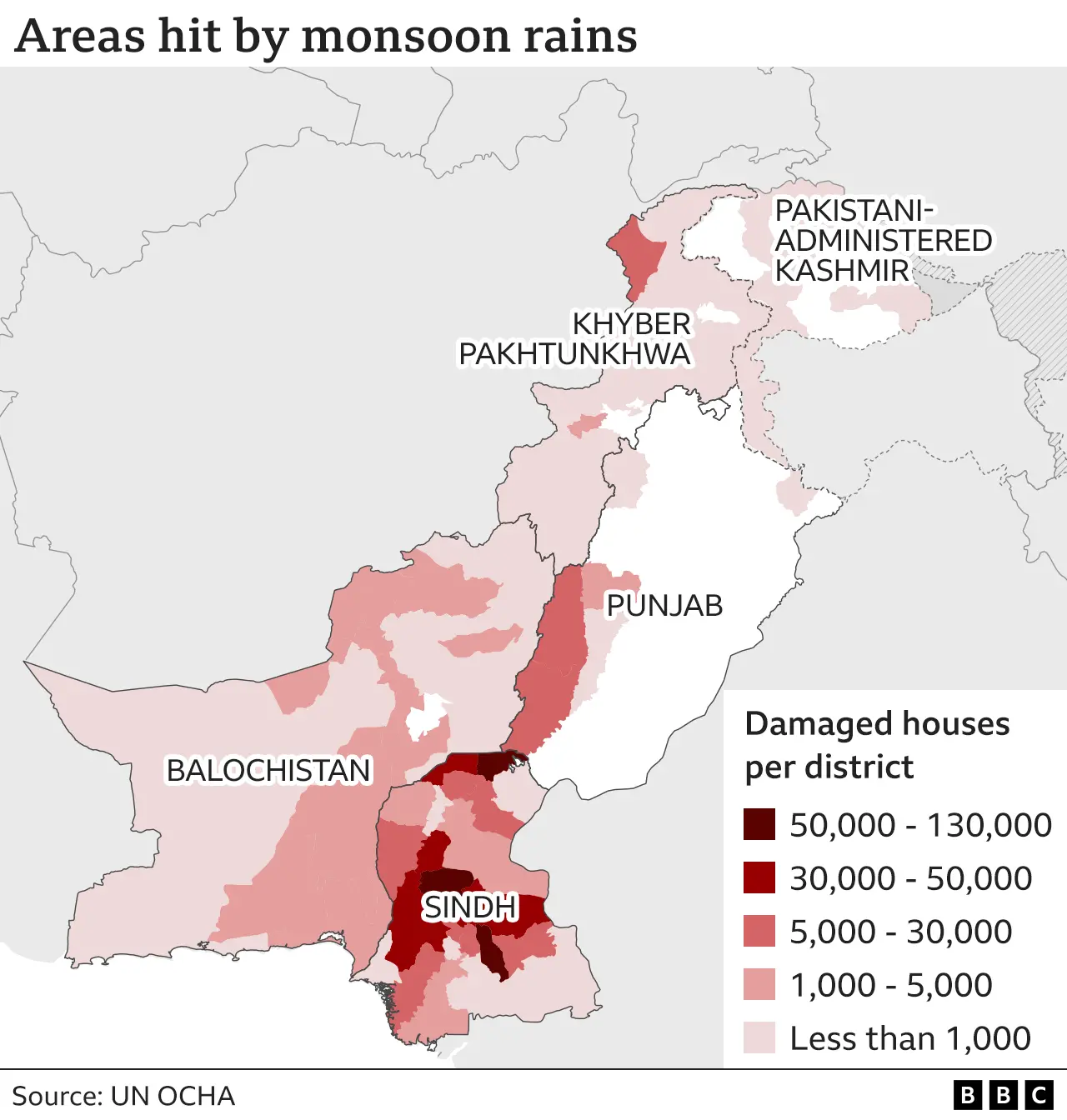

The floods were caused by record rainfall during the monsoon season and melting glaciers in the mountains.

The South Asian nation received nearly 190% more rain than the 30-year average, in July and August. The southern province of Sindh received 466% more rain than average.

When UN Secretary General António Guterres visited Pakistan last week, he blamed climate change for the disaster and said the country needed massive financial support.

"I have seen many, many humanitarian disasters in the world. But I have never seen climate carnage on this scale. I have simply no words to describe what I have seen today, a flooded area that is three times the total area of my own country, Portugal," Mr Guterres said.

Aid agencies are now assessing the scale of the reconstruction effort, and with entire villages underwater, a public health crisis is inevitable.

Weather officials say more rain is expected in the coming days, putting thousands of displaced people at further risk.