The 'forgotten' Afghan refugees taking their own lives

BBC

BBCSeparated from his distant loved ones, Ali Joya treated his friend Mujtaba Qalandari as family. The two Afghans shared both their nationality and years spent in Indonesia waiting for resettlement.

"He was a very bright person," Mujtaba says of Ali. "He'd always wished to settle abroad one day to support his mother, who is in Afghanistan. He always said, 'I want to make a future for myself - have a wife and children'."

But the wait was too long - Ali killed himself late last year. Still in his twenties, he had been awaiting resettlement for nearly eight years.

Mujtaba was numb with shock.

Ali is one of at least 13 Afghans in Indonesia who have taken their own lives in the past three years, according to Mohammad Yasin Alemi, who acts as a local representative for Afghan refugees in the city of Tangerang.

Each had been waiting between six and 10 years for the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) to tell them if they'd be given resettlement elsewhere. Most of them were believed to be in their twenties.

'We have been forgotten'

Afghans comprise 2.7 million of the UNHCR's registered refugees globally - the third largest nationality. Lack of security and political and economic instability after the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 have contributed to the exodus.

Nearly 8,000 Afghan refugees and asylum seekers were registered with the UNHCR in Indonesia as of December 2020 (about half of the overall total), but the country hasn't signed the United Nations Refugee Convention and bars their permanent settlement.

It is illegal for them to work, and so they typically cannot access or pay for health services and education. Many are confined to camps. Some have waited more than a decade for a third country to take them in, a process facilitated by the UNHCR.

It is a limbo 42-year-old Mujtaba Qalandari knows well. With his wife and son, he migrated to Indonesia in 2015 to escape the war in Afghanistan and find a better future.

His wife Gulsum gave birth to another boy and a girl in Indonesia. She says the wait has led to severe depression for her and her husband.

"We registered ourselves with the UNHCR in 2015. But we've not been contacted since then. We have been forgotten," the 34-year-old says.

Mr Alemi says he has seen the cases of suicide mount up.

"The main reason is the long process of resettlement through UNHCR. The minimum wait has been at least six years," he says.

"Financial problems, fear for the future, and anxiety are other issues which contribute to them taking their lives."

'He left me alone'

Elsewhere, people waiting for years to receive resettlement face similar hardships.

There are 1.4 million refugees globally who need permanent settlement in a country other than where they currently have asylum, according to the UNHCR.

This can be because of personal needs, security or lack of international treaties.

Worldwide, there were 26 million refugees and more than four million asylum seekers in 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic began.

Mujtaba Hossain is another Afghan who lost a close friend. The 22-year-old's roommate, Abdul, had been in Indonesia for seven years - a year more than him.

During that time Abdul, 36, had been hoping to reunite with his wife and two children, who could not travel with him to Indonesia. But Mujtaba says eventually, in December, "he gave up and ended his life".

The impact was devastating for Mujtaba - they were each other's only close friends in Indonesia.

"He was a very energetic person, he joked all the time, and his hobby was going to the gym," says Mujtaba. "We'd promised that wherever our lives led to, we'd meet again in the future. But he left me alone, in the middle of the journey."

Mujtaba still lives in Tangerang, in the cramped room with a single small internal window that he shared with Abdul. He says that a third of his life has been "wasted" in that room, as he waits for resettlement.

The UNHCR said it was "deeply saddened by the tragic loss of life of several refugees in recent years, which may have resulted from depression and mental health problems. This underscores the need for psychosocial care and support for all refugees."

It said it was continuing to work closely with "the government of Indonesia and partners to improve refugees' and asylum-seekers' well-being and mental health".

Ann Maymann, the UNHCR representative in Indonesia, said: "With educational and livelihood opportunities currently on hold due to Covid-19 restrictions, many refugees see resettlement as their only option for a meaningful future."

'The worst days of my life'

Most Afghans in Indonesia hope to be settled in a third country, particularly Australia. But host countries are accepting fewer new applications, as public attitudes towards taking people in appear to harden.

UGC

UGCThis is why people are waiting in Indonesia, the foreign ministry says. It calculates that in 2016, 1,271 refugees received resettlement to other countries from Indonesia - a number that fell by almost half the following year. By 2018 only 509 refugees were resettled.

Musa Sazawar, a 42-year-old TV journalist from Afghanistan, feels the cold reality of those statistics. Blinking back tears, he says when he left his wife in Ghazni province in south-west Afghanistan, she was pregnant.

"My son turned eight and I still haven't seen him in person. I haven't felt him yet. I haven't even hugged him," Musa says.

Musa's family had insisted that he leave Afghanistan after threats from local insurgent groups in the course of his work.

"My wife said, 'I will look after our sons'," Musa says. "'It's better if they grow up and know that their father is far away but alive. I don't want you to die and them to grow up as orphans.'"

A year after he left, Nato ended its combat mission in Afghanistan, the US withdrew a significant number of its troops, and violence surged across the country. Hundreds of thousands more Afghans were forced to flee.

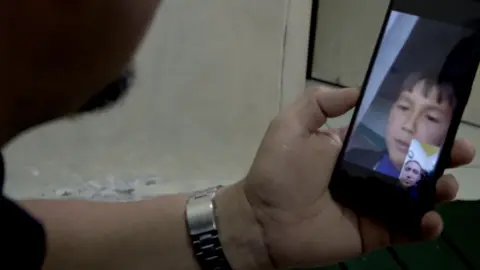

And now, 8,000 kilometres (5,000 miles) away, Musa must resort to video calls to see his family.

"It is very difficult. I can't even say that I am a father. But what is the solution? It's all because of these challenges: migration and the situation of the country that made us refugees."

After leaving to try to provide his family with a better future, he says it has yielded little except grief and frustration.

"The worst days of my life have been the years I have been far from home," he says.

Lesthia Kertopati, Silvano Hajid Maulana and Anindita Pradana contributed to this report.

If you, or someone you know, have been affected by any of the issues in this story, support is available via the BBC Action Line.