Afghanistan: A year of violence on the road to peace

BBC

BBC

A year ago this week, the Taliban signed a deal with the United States designed, in theory, to pave the road to peace in Afghanistan. It committed the Taliban to preventing attacks on US forces and the US to withdrawing its remaining troops from the country. It did not commit the Taliban to a ceasefire with respect to Afghanistan's government, or its citizens.

One Sunday morning last month, Qadria Yasini got ready as usual for work. She put on a new coat and woke her son Wali to say that she had left some money for food. Her driver wound through the Kabul neighbourhood on the way to the office, stopping to collect Yasini's friend and fellow Supreme Court judge, Zakia Herawi.

Yasini, who was 53, and Herawi, who was 47, were two of Afghanistan's roughly 250 female judges - a number which has risen steadily from zero under the Taliban two decades ago and amounts to about 14% of the country's total. The two women were not high-profile politicians; they were not military figures. Neither had ever received a warning from the Taliban, as many journalists and activists have. They were not accustomed to taking day-to-day security precautions. Yasini had recently turned down a government offer of a pistol, her family said. She didn't think she needed it.

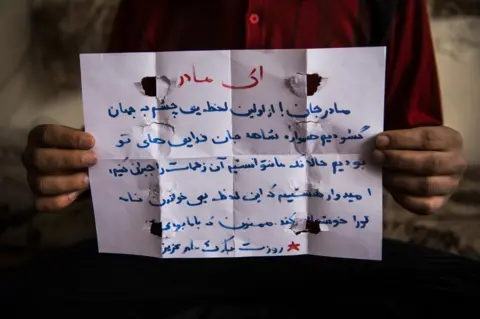

In the end, the pistol probably would not have saved her. The assassins knew where the two judges would be. They knew the car, the route. There were three of them. When they prized open the door, Yasini clutched her handbag to her chest and the five bullets that hit her passed through it, piercing her purse, her books, and a handwritten Mother's Day card from her sons that she had carried with her for the best part of a year. "She told us once that she looked at our card every day," her son Wali said.

Dear Mother! From the first time that we opened our eyes to this world we witnessed your self-sacrifice for us. We cannot compensate you for what you have done, but we hope that, in this moment, this card will make you happy. Thank you for being with us! Happy Mother's Day!

Wali, who is 18, and his brother Abdullwahab, who is 19, heard from their uncle by phone that there had been an attack. They waited at home, for their own safety, and eventually police came with their mother's bullet-holed bag. When they were shown CCTV footage of the assassination, the brothers saw the gunmen escaping on motorbikes, shouting Allahu akbar - God is great. They saw boys their own age.

"Young people like I see every day at school," Wali said, ruefully. "You would never think that they could kill your mother."

BBC

BBC BBC

BBC

A year on from the US-Taliban deal, a wave of targeted killings of civilians has terrorised Afghanistan, even as the nation seeks a political route to peace. Assassins have come for the country's judges, journalists, and activists, using motorcycle drive-by shootings and magnetic "sticky bombs" hidden under cars. They have killed people who long expected their life to be cut short and people who had never received so much as a warning they were at risk.

The assassinations surged after intra-Afghan peace talks began in September. According to figures published by the UN on Tuesday, 707 people died in targeted attacks last year - nearly half of those in the last three months. Overall, the number of civilian casualties fell, because the number of US airstrikes and large-scale Taliban attacks fell (though the civilian death toll from Afghan Air Force strikes rose sharply). The death toll from assassinations increased by 45%, according to the UN, and expanded to include even softer targets than Afghanistan was used to.

Adding to the climate of fear, many of the assassinations have gone unclaimed. "People are dying, bombs are exploding, and no one is taking responsibility," said Habib Khan, founder of the monitoring group Afghan Peace Watch. "The Taliban used to fight in big numbers, they would overrun district headquarters and city urban centres," he said.

Then came the deal with the US, secret annexes of which reportedly committed the Taliban to foregoing complex attacks in major cities. That prompted the group to "shift its focus from military attacks to targeted assassinations", Mr Khan said.

BBC

BBC

The lack of claims of responsibility has led some to accuse affiliates of the so-called Islamic State group, or suggest political factions are taking advantage of the chaos to settle scores. But few doubt that the Taliban have been behind the majority of the killings.

"Everybody hoped that through the US deal the Taliban would transform from a military force to a political force or quasi-political force - basically that they would change," said Tamim Asey, a former deputy defence minister of Afghanistan. "But nobody sees any indication the Taliban has changed. They simply changed their tactics; they are assassinating because it is not strictly against the deal."

The Taliban have been accused of using the assassinations to eliminate their critics ahead of a return to power, and instil a deep fear in those left alive. If you ask Wali Yasini who killed his mother, he will say only that it was a "powerful religious group".

"I know what you are asking but I'm not really… I just can't say who was responsible," he said.

Now, as the US draws closer to its 1 May deadline for troop withdrawal, the Taliban appears to be shifting the balance of its strategy back towards major military operations. Some believe a withdrawal extension could be peacefully negotiated, but were the US to remain in the country longer, as many Afghan officials hope, the Taliban would likely see it as a violation of the Doha deal and a justification to return to war against the Americans. The country is in a precarious state.

BBC

BBC

Qadria Yasini came of age before the Taliban seized power in 1996. She grew up in a relatively modest family in Kabul, the daughter of a car mechanic and homemaker, but her mother pushed her to embrace school.

"Our mother didn't have much opportunity to study but her dream was to be educated," said Qadria's older sister Shukria, now 57 and a lecturer in law at Kabul's Aryana University.

"She told us that when individuals become educated all of society becomes a little better educated, and in that way you can change your country."

Young Qadria stood out even amid her bright and diligent brothers and sisters. She loved the French language and later French films. Aged 11, she passed the entrance exam for the Lycee Malalai - a leading French school for girls that was free to attend. Her time there was a joyous period in her life, her sister said. It paved the way for a law degree at the University of Kabul and a job offer to write for a journal of the Supreme Court. After two years on the journal, Yasini joined the law department at her old university and then, aged just 25, she passed the judicial entrance exam - the gateway to becoming a judge.

Yasini's friend Zakia Herawi, who died alongside her last month, also moved quickly from her law degree to completing a judicial internship. She finished first in her class, her brother Haji Mustafa Herawi said. "She loved the law," he said. "And she loved her country."

Herawi graduated a few years after Yasini, but before either judge could join the bench Afghanistan fell into civil war and both the Yasini and Herawi families fled to Pakistan. Four years later, the Taliban swept into Kabul, shuttered the Lycee Malalai and told Afghanistan's girls to stay home.

Yasini waited patiently in Peshawar, Pakistan. She studied English and midwifery and wrote articles for a law journal. She married a man she had known in Afghanistan who had also fled. But she dreamed of returning home. "The instant the Taliban was pushed out of power she left for Kabul," her sister said.

Herawi and her brother, who had worked in a clothes factory in Pakistan, returned about six months later. "She applied for a job as we arrived in Kabul, and believe me within two days she was again a professional member of the Department of Research and Studies," he said proudly.

Yasini worked as a midwife for a while after returning, but eventually she found her way back to the law. She published journal articles and a book on inheritance law and, in 2010, finally became a judge. She had two sons - Abdulwali and Addullwahab. Then about five years ago, when the boys were 12 and 14, their father left the family to start another. Alone with them, Yasini redoubled her emphasis on their education, Wali said. "All of my achievements are because of my mother's encouragement to study."

BBC

BBC

Wali is a talented artist and linguist, but his dream is to study medicine abroad before returning to Afghanistan. His brother Abdullwahab, born the year the Taliban fell, is a student of economics at the University of Kabul. Abdullwahab was at the university last November when gunmen stormed the campus and killed 22 of his fellow students, setting off a frantic effort by his mother to reach him and a wave of relief when she heard he was OK.

By the time the gunmen came for her and her friend, last month, there had been so many assassinations in Kabul that the killings had lost some of their power to shock. The fact that the two women had never spoken publicly against the Taliban, or anyone for that matter, might have made their deaths seem senseless. But the attack embodied the strategy the Taliban have been accused of pursuing - wounding the institutions the government relies on and sending a warning to women about what they should and shouldn't do with their lives.

"When these women were killed I kept thinking about how hard it is for a woman to become a judge in Afghanistan, how much difficulty they must have overcome, and how brutal it is that after all that they would die in this way," said Shaharzad Akbar, the chairwoman of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission.

"So many times Afghan women have been told they don't have a place in public life. But women like these two persevered, they continued to hope, they stayed in their country, invested in their country and fought for a better future for everyone. And it makes the loss all the more heartbreaking."

BBC

BBC

This past Tuesday, the Taliban and Afghan government negotiating teams announced they had resumed talks after weeks of deadlock. Going into the talks, the Taliban maintain they are committed to a political solution, and claim they bear no responsibility for the wave of assassinations that has terrorised civil society.

In Kabul, many activists are either leaving the country or curtailing their lifestyles. "I don't drive any more in Afghanistan," said Dr Patoni Isaaqzai, a women's rights activist in Kabul. "I take a taxi or borrow a car. I go out only when I have to. These are small things but I am not alone - people are fearful.

"If you want to know if I am afraid, yes I am," she said. "I am afraid."

Mr Khan, the founder of Afghan Peace Watch, said he rarely leaves the small compound that contains his home and office. "People are adapting to this harsh new reality," he said.

He and his fellow activists fear an even harsher reality should the US push ahead with its planned troop withdrawal by 1 May. There are hopes that President Biden will delay the withdrawal and put greater pressure on the Taliban to seek a negotiated peace, but as the anniversary of the Doha deal approaches everything remains uncertain. Both sides are bracing for war.

"If they stick to the May deadline and withdraw abruptly Afghanistan will plunge into civil war," said Mr Asey, the former deputy defence minister. "You will see al-Qaeda revived and other terror groups revived, and they will use Afghanistan as a safe haven to launch attacks. The US will lose interest and leverage, and Afghanistan will turn into another Syria or Libya."

BBC

BBC

For the family members of those assassinated this past year, there is no road back to their loved ones in this lifetime. Many do not even know for certain who killed them. They cannot do anything to affect the outcome of the peace talks or the withdrawal arrangements; only carry their grief with them and attempt not to give into it.

"This pain I have experienced, that my mother and sister have experienced, I do not want anyone else to experience this pain," Mustafa Herawi said, his eyes full of tears.

Qadria Yasini's sister Shukria said she would ignore the risks and carry on her work for the Ministry of Women's Affairs - travelling the country teaching young women from rural areas about their opportunities and rights. As of last week, she had held classes in 32 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces.

"I have no fear of the Taliban," she said. "The Taliban can threaten me but I will still be working for the women of Afghanistan. They deserve to know that they are valuable to their country, and that they have a huge value to society."

Back in early 2019, around the time the US and Taliban met for the negotiations that would lead to their deal, registration for Afghanistan's judicial entrance exam went online for the first time, with the goal of bringing more women from the provinces to the bench. According to the Supreme Court, there are currently 99 women around the country training to become a judge. "That number needs to keep going up," Shukria said. "My sister would have wanted it. And women make good judges."

Photographs by Andrew Quilty for the BBC