Viewpoint: Pakistan's dirtiest election in years

AFP

AFPThe run-up to Pakistan's general election on Wednesday has been marred by allegations of pre-poll rigging, intimidation and the muzzling of the media, writes Gul Bukhari, who was briefly kidnapped by masked men in Lahore's army cantonment area in June.

Until a few months ago, protest chants accusing Pakistan's powerful military of terrorism were rarely heard in the country's main cities.

But they came to central Lahore on 13 July, the day former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and his daughter Maryam returned from London to begin their prison sentences.

By last Friday, the chant - "ye jo dehshat gardi hai, is ke peehchay wardi hai" ("the military uniform is behind this terrorism") - could be heard on the streets of Rawalpindi, not far from military headquarters.

In a stunningly brazen move, a hearing for a seven-year-old narcotics case involving Mr Sharif's PML-N party stalwart Hanif Abbasi was moved forward from August to 21 July, and a life sentence handed down at 23:30 on Saturday, four days ahead of the general election, effectively knocking him out of the race.

Mr Abbasi was the frontrunner in his constituency against Sheikh Rashid Ahmed, who served in both Gen Zia and Gen Musharraf's governments and is an ally of Mr Sharif's arch-rival Imran Khan, who leads the PTI party. Any focus on the merits of the case was overshadowed by outrage at the timing of the verdict.

Thousands attended rallies to welcome Nawaz Sharif back, but the media did not carry any of the protests in Lahore or Rawalpindi. Social media, in contrast, was flooded with pictures, videos and discussion.

EPA

EPAContrary to the establishment's expectations, the popularity of Mr Sharif and his party held its ground after he was ousted on corruption charges in July last year. His accusations of military interference caught the public's imagination.

To counter this, a fierce crackdown on the media was unleashed. Market leader Geo Television was taken off air in April, and the distribution of Pakistan's oldest newspaper, Dawn, has been disrupted since May.

After months of financial losses, Geo reportedly agreed to the security establishment's demands to self-censor and abide by strict guidelines. After this surrender, the industry as a whole fell into line and none of the media houses dared show Mr Sharif's political rallies or his daughter's fiery speeches.

More on Pakistan's election

With the media on its knees, it was left to activists on Twitter and Facebook to continue the fight. The voices here remained feisty and openly angry at the judicial-military nexus, accusing them of violating their mandate and preventing voters from exercising their will in the general election.

The conversation on social media continues to survive and thrive amid a terrifying onslaught of threats and abductions. Journalists, too, have taken to social media to air what they cannot on their screens or in their newspaper stories and op-eds.

Mr Sharif seems to have won this round of the battle. Seen as a man who could have lived a comfortable life in exile and attended to his seriously ill spouse, he has returned to Pakistan to face certain incarceration in his fight for civil supremacy.

Successive opinion polls putting him ahead against all opponents, and the social media backlash, indicate he has managed to win sympathy for himself - and resentment at attempts by the judicial-military nexus to re-engineer the political landscape.

With two days to go before the election, unexpected public defiance, especially in Punjab, a PML-N stronghold and hitherto a bastion of military power, has led to redoubled efforts to tip the scales in favour of the security establishment's favourite, Imran Khan.

Allow X content?

With dimming hopes the public will reject Mr Sharif and embrace the former cricketer-turned-politician, the courts have been redeployed at the frontlines - Mr Abbasi's shock life sentence being a case in point.

Clearly, with scores of candidates disqualified, jailed or coerced away from standing for the PML-N, and journalists and social media users harassed amid an atmosphere of terror, Mr Sharif's party is no longer expected to sweep the polls come 25 July.

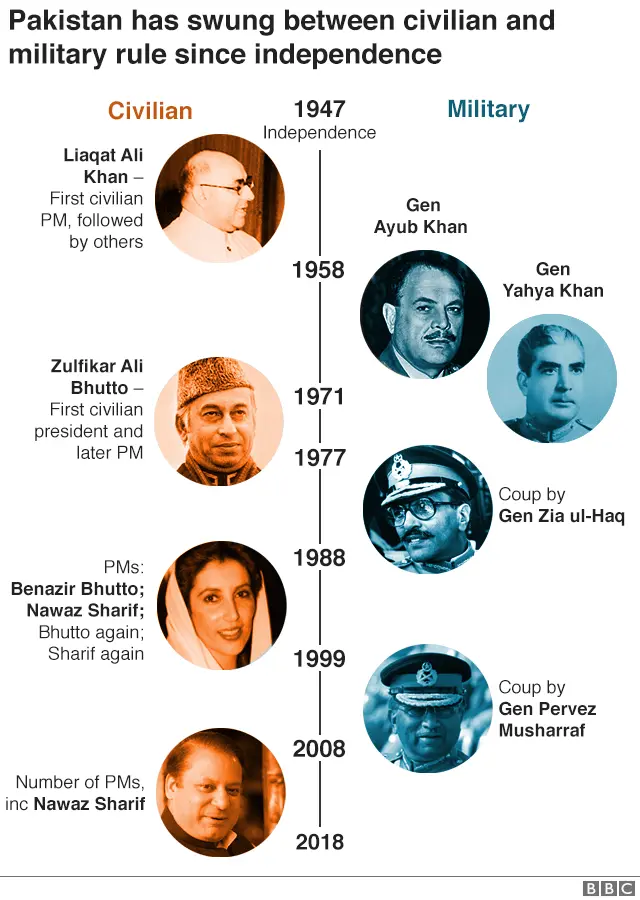

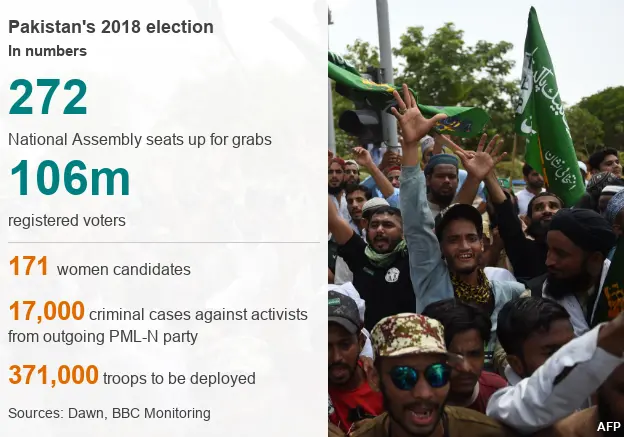

But if his party bags anything over 90 of the 272 directly elected seats in the National Assembly, down from about 130 in 2013, it could well remain the largest party in parliament. That would be viewed as a vindication of Mr Sharif's open defiance of the military, which has ruled Pakistan for nearly half of its history.