A war of nerves between Pakistan's military and Sharif

Reuters

ReutersPakistan's oldest and most prestigious newspaper, Dawn, is feeling the squeeze, weeks before a general election.

Its distribution remains suspended across large parts of urban Pakistan that are controlled by the army's real estate giant, the Defence Housing Authority (DHA), as well as in military garrison areas where many civilians live.

And Dawn is not alone.

In March, the country's largest television news network, Geo, was widely blocked by cable providers in military-controlled areas, while elsewhere it was moved lower down the channels list.

Both developments suggest an escalating war of nerves between deposed prime minister Nawaz Sharif and the powerful military.

What prompted the blockades?

Pakistan's civilian authorities say they have not ordered them. So attention turned to the security establishment.

AFP

AFPThe action against Dawn comes in the wake of a Nawaz Sharif interview it published earlier in May, in which he questioned the wisdom of "allowing" Pakistani militants to cross the border and kill 150 people in Mumbai.

He also asked why Pakistan had not prosecuted the mastermind of the 2008 Mumbai attacks, who was arrested in Pakistan but has since been surreptitiously released.

The comment was seen as a broadside at the military, which is widely believed to harbour militants and which Mr Sharif has openly blamed for being behind his disqualification from office last year.

One of its reporters closely followed the corruption case against Mr Sharif, and dug up information that suggested the grounds on which he was disqualified had been "extremely weak".

Why would the military worry?

Critics of the military say it is trying to control the media at a time when its business empire is being challenged on two fronts.

The first was opened by Mr Sharif who, after being ousted by the Supreme Court, has grown increasingly defiant.

This is all the more menacing given that his popularity hasn't shown any visible signs of diminishing, which creates an uncomfortable possibility for the army that he may win the election if not stopped.

Alamy

AlamyThe second front is the rise of a grassroots movement from the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata), the base from which the military has allegedly orchestrated its regional proxy wars.

The Pashtun Tahaffuz (Safety) Movement (PTM) is expressly peaceful but its leaders have inside knowledge of how those proxy wars were orchestrated and what price local people paid. They have been asking uncomfortable questions at mass rallies across the country. An unannounced ban on their coverage is also in force.

So the military faces two opponents at once.

While the PTM has the potential to evolve into a fearsome adversary, the threat posed by Nawaz Sharif is of a more immediate nature.

What does Sharif know?

Loads.

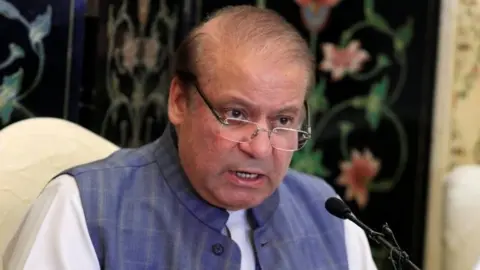

Reuters

ReutersNawaz Sharif has been prime minister three times since 1990, and his association with power goes back to 1980 when military ruler General Ziaul Haq appointed him finance minister of Punjab.

As such, he is privy to how the military evolved into what some call a "sovereign" entity in its own right.

He was an early ally of the military, and was in the forefront of a political alliance - bringing together ultra-right wing groups and political fronts for militant organisations - that was cobbled together by a former chief of the ISI intelligence service soon after the death of Gen Zia in an air crash in 1988.

Mr Sharif is named among recipients of cash distributed by the ISI to members of the alliance to fight elections.

He also knows the inside story of the 1999 Kargil war, when he was prime minister. Pakistan said it was the work of Kashmiri militants, but it was later revealed that Pakistan's army had orchestrated the conflict.

Mr Sharif has indicated on a couple of occasions that the war was planned and executed by then army chief Gen Pervez Musharraf behind his back. But he is yet to come out with the full story.

Analysts believe the war was meant to scupper Mr Sharif's efforts to normalise relations with India. Tensions with Gen Musharraf culminated in the army coup of 1999 in which he was overthrown and exiled.

And Mr Sharif is also privy to the military's strategy of employing militants to wage wars in Afghanistan and India from their sanctuaries in Fata.

How far might Sharif go?

But the question is, will Mr Sharif go the whole hog and spill the beans to the military's detriment, especially once his party hands power to a caretaker administration later this month ahead of the general election?

There are high stakes. Since the 1980s, the military has evolved into the country's largest business empire, while developing a capacity to control the country's political decision-making.

At home, the military derives its main strength and support by painting India, and at times Western powers such as the US, as a perpetual enemy.

But experience shows that politicians, whenever they were in firm control of affairs, have invariably tried to normalise relations with India.

"This may be one reason why successive civilian governments that warmed to India have been pulled down through covert subversion," says Afrasiab Khattak, a former senator and head of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan.

When civilian governments have been destabilised in the past, religious and militant groups - the judiciary now, too, some would say - as well as "surrogate" politicians have been deployed.

Something similar is happening in Pakistan right now. And Mr Sharif is at the centre of it, threatening the military with uncomfortable truths. Or perhaps seeking a deal.

What is clear is the media are being gagged like never before, and efforts are under way to drive a wedge into Mr Sharif's PML-N party before the elections can be announced.