Nigeria turns 60: Can Africa's most populous nation remain united?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn our series of letters from African journalists, novelist and journalist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani considers the greatest challenge facing Nigeria as Africa's most populous nation marks 60 years of independence from the UK.

How to keep a multitude of ethnic groups united and satisfied? This was the greatest hurdle Nigeria faced in the first decade of its independence - and continues to be the case 60 years later.

Heated national conversations usually revolve around which ethnic group gets what, when, and how. Or how fairly a person from one group was treated compared to one from another.

A major policy to promote systemic equality was launched by the Nigerian government almost four decades ago, but it has led to further balkanisation and bitterness.

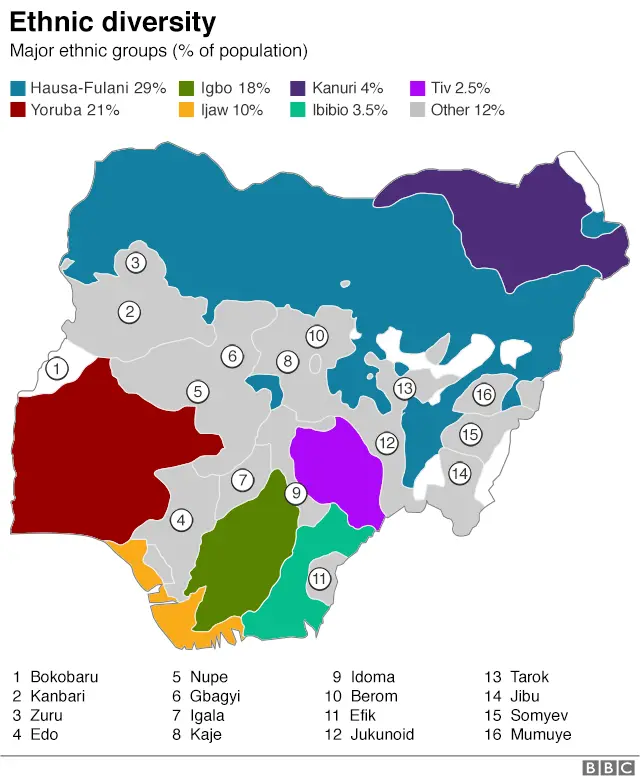

Nigeria is home to more than 300 ethnic groups and three dominant ones: the Igbo in the south-east, the Yoruba in the south-west, and the Hausa in the north.

These groups were separate entities before the British merged them into one country that today operate as a federal system - with power concentrated at the centre and distributed among the 36 states and the capital, Abuja.

Struggles for power at the centre or concerns about unfair treatment have at different times led to pogroms, protests and violent conflict, including the civil war of 1967 to 1970, sparked by an attempt by the Igbo to secede and form a new nation called Biafra.

To foster inclusion, the "federal character principle" was enshrined in Nigeria's 1979 constitution.

It includes a provision for public institutions to reflect the "linguistic, ethnic, religious and geographic diversity of Nigeria".

At first, this seemed to appease all sections of the country.

Educational divide

But, today, it is one of the most contentious government policies, with many Nigerians complaining that it has done more damage to our country than good.

Local newspapers regularly feature headlines such as: "Federal Character a curse to Nigeria" or "Group calls for an end to Federal Character".

For starters, "federal character" was not accompanied by any strategy to end the vast educational inequality that has always existed between Nigeria's majority Muslim north and mainly Christian south.

This disparity is the result of a complex combination of factors, such as religion, culture, past colonial policies and, more recently, the Islamist militant Boko Haram insurgency.

Nigeria has 13 million out-of-school children, the highest in the world, according to Unicef, and more than 69% of them are in the north.

As a result, the region has Nigeria's lowest literacy rates, with some states recording just 8%.

Yet, this same region must still fill its quota in public institutions - quite a massive chunk since it has a population of 90 million out of Nigeria's 200 million, and 19 of 36 states, plus Abuja, totalling 20.

"Regrettably, 'federal character' has become a euphemism for recruiting unqualified people into the public service," said Ike Ekweremadu, a former deputy president of Nigeria's senate.

"These employees decrease productivity, weaken our public service, and ultimately render it inefficient."

These unqualified can easily rise above their more qualified colleagues, as "federal character" is also applied when filling senior positions in public institutions.

In addition, rivalry between ethnic groups often leads people to lift as many of their kinsmen as they can once they find themselves in a position to do so.

Northerners have ruled the country for 38 out of Nigeria's 60 years of independence, mostly via military coups.

I have listened to many Nigerians tell bitter stories of working hard without reward while some colleagues simply lounged their way to promotion because their kinsman was in power.

Thanks to "federal character", ethnic solidarity and striving to be in positions of authority tend to take pre-eminence over self-improvement and excellence.

Almost every year, livid social media posts, newspaper columns and parliamentary debates follow the publication of cut-off marks for the exams which determine who gets into Nigeria's top government-run secondary schools.

Students from some states in northern Nigeria sometimes require scores as low as two out of 200 to be admitted, compared to students from states in the south who need scores of at least 139.

'Best team fielded'

Merit and excellence are often sacrificed for diversity when appointing heads of government ministries, as "federal character" also makes it mandatory for each state to have a representative in the president's cabinet.

Many of Nigeria's best brains never get the opportunity to move their country forward with their knowledge and skill ignored because there is a large pool of talent in their state.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Nigeria won the U-17 World Cup for the fifth time in 2015, critics of "federal character" were quick to point out the lack of diversity in the national team.

Nigeria simply went to the tournament with her best.

Prior to the match, the national coach, Emmanuel Amuneke, was criticised for apparently populating the team with players from his south-east region.

You may also be interested in:

He was forced to explain that he had simply chosen what he considered the best, without paying attention to their place of origin.

Some Nigerians argue that "federal character" is indispensable to national unity and simply needs some tweaking to work.

Qualified people exist in every region and just need to be searched out.

After all, some of Nigeria's globally acknowledged top brains in many fields are from the educationally disadvantaged north.

"I believe we should have Nigerians from all over the country in public office," said Lamido Sanusi, a former central bank governor and emir of Kano in the north, who in March was deposed by his state government under controversial circumstances.

"But all those Nigerians must be people that are competent. There must be a merit test, a competence test."

Power politics in Nigeria:

- I October 1960: Nigeria gains independence, followed by two coups in 1966

- 1967: Three eastern states secede, sparking three-year Biafra civil war

- 1979: Elections bring to power Shehu Shagari, who was ousted after four years - and a series of coups and military governments followed

- 1993: The military annuls elections when preliminary results show victory for Moshood Abiola

- 1999: Democracy returns a year after the death of military ruler Gen Sani Abacha

- 2015: Muhammadu Buhari becomes first opposition figure to win a presidential election since 1960

President Muhammadu Buhari has been frequently vilified even by opponents of "federal character", for appearing to abandon this policy.

"I don't have a problem with any part of Nigeria but I have a problem with the way government is directing its appointments," said Mr Ekweremadu during a fiery session in parliament in 2018.

At present, 17 out of Nigeria's 20 service chiefs appointed by Mr Buhari are from his northern region, while 16 are Muslim like him.

And 15 out of 21 serving assistant inspectors general of police are from the north, while 16 are Muslim.

In defence of his boss, presidential spokesperson Garba Shehu told me: "Are you going to give your command positions in the military to people you don't trust?"

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFormer President Olusegun Obasanjo, once a supporter of Mr Buhari, recently accused him of "mismanaging diversity" and being responsible for a Nigeria that is today more divided than at any previous time in the country's history.

Nobel laureate and writer Wole Soyinka shared a similar view last month, making reference to "a culture of sectarian privilege and will to dominate".

However, Mr Buhari's spokesperson pointed out that previous administrations also faced the same accusation.

"When you are not on seat [in office], you always see the wrongdoing of others," Mr Shehu said.

"When Obasanjo was in position, he was also accused of appointing people from the south-west."

Some radical groups in the south now believe that the only solution is for Nigeria to split, with each major ethnic region becoming a country of its own.

Some politicians and pundits prefer "restructuring" with each region having more autonomy, which would keep Nigeria united but significantly reduce power at the centre.

Whatever resolution Nigeria eventually takes as it enters its 70th decade of independence, one thing is certain: the country's future depends on how successfully coming governments can maintain unity in diversity.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica