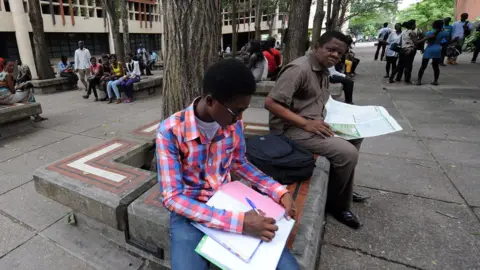

Letter from Africa: Why Nigeria is failing teachers and pupils

AFP

AFPIn our series of letters from African journalists, the editor-in-chief of Nigeria's Daily Trust newspaper, Mannir Dan Ali, considers why Africa's most populous country is struggling to educate its children.

Nasir El-Rufai, the governor of Nigeria's Kaduna State, likes to make headlines.

While receiving a visiting World Bank delegation recently, he revealed that a test given to primary school teachers had elicited startling results.

They had been given questions set for primary four pupils, who are aged 10.

The teachers had been expected to score at least 75%, the governor said.

"But I am sad to announce that 66% of the teachers did not get that."

He blamed the hiring of unqualified teachers for the problem and promised to put an end to it.

But the state's teachers' union secretary, Adamu Ango, has disputed the governor's claim, calling it cheap media propaganda.

He has challenged him to make the examination paper public and measure the results alongside internationally accepted teaching competency examinations.

Unsurprisingly, teachers in the state are not happy - especially with the frequent tests they are made to take, saying this is the third such test in within a year.

AFP

AFPAll other test results should be made public, if the governor is to be fair to them, they argue.

And could the governor not also release some of their outstanding allowances unpaid for two years now?

Both sides may be right up to a point.

Teachers are not known to be motivated - and it is not a career path many Nigerians opt for by choice.

Many see it as a stop-gap before getting their dream job.

Mannir Dan Ali:

Mannir Dan Ali

Mannir Dan Ali"Recruitment has also become a nightmare for employers who come across graduates unable to string together five correct sentences"

Class sizes are also a big issue.

A teacher friend of mine once invited me to her primary school where class sizes ranged from 90 to 120 plus pupils.

Even the most enthusiastic teacher would have trouble getting the attention of such a class, most of whom are likely to be seated on the floor, winking, pinching and playing pranks - making learning almost impossible.

Politicians also prefer to commission contracts to build classrooms that can be seen from the outside, rather than equipping them or training and motivating the teachers to do their work inside them.

There is also an over emphasis on gaining certificates, even those of doubtful quality.

'Miracle centres'

So many schools are only keen to churn out students with the required grades on paper but who cannot defend them in practice.

It has also led to the proliferation of what are called "miracle centres'' - schools or examination centres where almost everybody is guaranteed a good grade at a price.

A relation who teaches at one publicly funded school told me that thanks to such "miracles", he has encountered students who have spent 12 years in basic education but who are unable to even copy the answers to exam questions that teachers write up on blackboards for them to copy out.

This explains why in addition to the national exams needed to gain admission to universities, polytechnics and other colleges, these higher education institutes insist on conducting their own separate tests to make sure that all the wonderful marks a candidate professes to have are genuine.

AFP

AFPRecruitment has also become a nightmare for employers who come across graduates unable to string together five correct sentences.

With basic education in such a bad state, especially in publicly funded schools, well-off parents have been voting with their money to send their children to private schools.

Indeed the class division in Nigeria is especially glaring in terms of what school one's child attends.

Student exodus

Meanwhile, there has been an explosion of universities from just two at independence to the current 155.

But frequent strikes have meant that students are never sure how many years it will take them to graduate, even though on paper their course it is for a specified period.

This has prompted a big exodus of students who can afford to go to tertiary institutions in far flung corners of the world.

Those unable to finance fees and other costs in the US, Europe or Asia go closer to home, opting for the Benin Republic, Ghana, Uganda and other African countries.

In fact some of the private universities in Ghana, Benin and Niger were set up by Nigerians eager to cash in on such opportunities.

Since only a fraction of Nigeria's population can afford to pay the fees for private schools and universities, fixing the public school system remains the only sustainable way for the country to adequately educate its citizen, if only to a basic level.

On the whole, most Nigerians agree that there is a crisis in the education sector - though there is no agreement on the reason why and how best to tackle it.

A shock-and-awe approach like that of the Kaduna governor may grab headlines, but it is unlikely to improve the morale of capable and committed teachers who are the corner stone of any education system.

More from Mannir Dan Ali:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa, on Instagram at bbcafrica or email [email protected]

AFP

AFP