How does Felix Tshisekedi's poll victory in DR Congo add up?

Felix Tshisekedi has been named as the provisional winner of presidential elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a historic victory for an opposition leader.

But questions have been raised about the accuracy of the results amid accusations that Mr Tshisekedi is planning a power-sharing deal with outgoing President Joseph Kabila.

The electoral commission said Mr Tshisekedi had received 38.5% of the vote on 30 December, compared to 34.7% for Martin Fayulu, another opposition figure. Ruling coalition candidate Emmanuel Shadary took 23.8%.

Those raising doubts about the results include the country's influential Catholic Church, international experts based in the US, and the French and German governments.

What's the evidence?

The accusations of fraud are based upon two partial sets of data, leaked from two distinct sources, that are said to corroborate each other while contradicting the official results.

The data sets have been analysed by journalists from three outlets - including the Financial Times newspaper - working alongside a New York-based think tank, the Congo Research Group (CRG).

The first set is said to have been drawn from the electronic tally collected by the National Election Commission (Ceni). The data here is believed to represent 86% of the total votes cast.

It indicates Mr Fayulu won 59.4% of the vote and Mr Tshisekedi came second with 19%. A third candidate, Emmanuel Shadary, representing Mr Kabila's governing coalition, seems to have polled 18.54%. The set was leaked by a person inside Ceni who is close to Mr Fayulu's camp.

Reuters

ReutersThe second set was leaked from data collected by the National Episcopal Conference of Congo (Cenco), a Catholic Church body whose observers are said to have visited all 75,000 polling stations.

The data in this leak represents 43% of the turnout. It indicates that Mr Fayulu secured 62.8% of the votes against Mr Tshisekedi's 15%, while Mr Shadary polled 17.99%.

Jason Stearns, the director of the CRG, told the BBC that the second leak gave a "real indication" that the data was plausible.

The two sets of data are "almost identical, not exactly identical, but uncannily identical", he said.

Cenco has not officially released any data, saying only that its findings did not match the official results. When contacted by the BBC, it refused to authenticate the data in the leaked set.

Ceni representatives have meanwhile rejected the fraud claims as fake.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesData from opinion polls conducted before the 30 December election also cast doubt on the official results, according to Pierre Englebert, a professor at Pomona College and senior fellow at US-based think tank, The Atlantic Council, who has studied DR Congo.

"The probability Tshisekedi could have scored 38% in a free election is less than 0.0000," he wrote, pointing to polling data by Berci and Ipsos for the CRG.

In an article for online magazine African Arguments, Mr Englebert said the data predicted:

- A 95% chance that Mr Tshisekedi would get somewhere between 21.3% and 25% of the vote

- Mr Fayulu would have obtained between 39% and 43% of the vote

- Mr Shadary would get between 14% and 17.4%

Mr Englebert acknowledged that opinion polls could be wrong, saying the official results could be correct if turnout was as high as 90% in Mr Tshisekedi's strongholds and really low, around 30%, in Mr Fayulu's strongholds. But he argued that this was extremely unlikely.

So how would fraud be possible?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are many ways to rig an election.

Academic Nic Cheeseman, who has written a book on how to do just this, told the BBC that if the election was rigged it probably happened during the collation of the results.

He said very few people would have to be involved in this.

"It's very easy. You can have a small number of people in a central office who release the result.

"You can have one person just adding a 1,000 votes to one candidate and subtracting 1,000 from another on an Excel spreadsheet."

He said the risk of fraud was normally avoided by observers tabulating the results in parallel. That did take place, but we do not have the data.

Throughout the election campaign, the use of electronic voting machines was a major source of contention. Voters used the tablet-like devices to select candidates, and then it printed their ballot paper with their choices. The machines were also meant to keep an electronic tally to help verify the results.

But Mr Englebert says that in the days following the vote, election observers reported that some of these machines went missing.

Why is the Church not announcing who it thinks won?

The observers were prohibited by law from releasing their findings before the electoral commission had announced the official results. It is not clear whether the law applies after the official announcement.

But the Catholic Church knows from the experience of past crackdowns that leading people on to the streets can have tragic consequences - and the ruling coalition has warned against "preparing the population for insurrection".

Séverine Autesserre, author of the book The Trouble with Congo, says the Congolese police have been brutal in their dealings with protesters in the past.

She told the BBC that if the Church, whose followers make up about 40% of the country's 80 million population, were to announce that Mr Fayulu had won - the consequences could be dire.

AFP

AFP"You would have huge, violent protests. You would have riots," she told the BBC.

"The police would crackdown on the protesters and that would result in a lot of deaths."

Last Friday, Catholic bishops urged the UN Security Council to put pressure on the Congolese electoral commission to publish the full results from each polling station.

Could the 'missing million' have made a difference?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYes, according Mr Englebert.

The election has been postponed until March in three areas: Beni and Butembo in eastern North Kivu province and Yumbi in the west of the country. An Ebola outbreak and insecurity were given as the reasons for the delay.

That amounted to more than 1.7 million voters, more than the number of votes separating the leading candidates.

Some of the those disenfranchised were in Mr Fayulu's strongholds, he says.

What happens next?

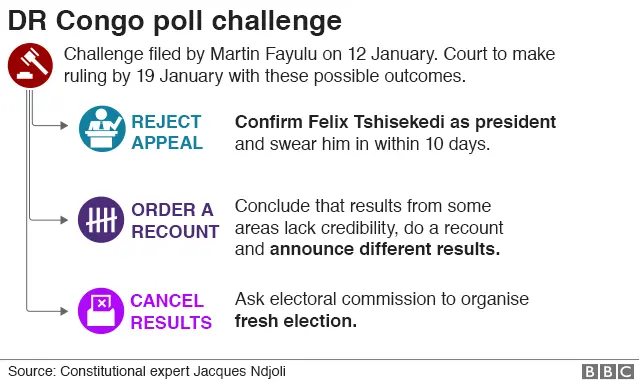

Mr Fayulu filed his challenge to the result in the Constitutional Court on Saturday. Judges have seven days to deliberate.

Constitutional expert Jacques Ndjoli told the BBC that there were three possible outcomes:

- The court could confirm Mr Tshisekedi's victory

- It could order a recount

- Or cancel the results altogether and call fresh elections.

International pressure to resolve the dispute may play a role but members of the UN Security Council are split. Countries like Belgium and France believe there has been fraud but Chinese and Russian diplomats have stressed that DR Congo's sovereignty and the authority of the electoral commission must be respected.

Corneille Nangaa, head of the electoral commission, has defended the results and accused Cenco of bias.

He told the Security Council about the difficulties the commission had overcome to register 40 million voters for the vote that had taken place amid relative calm, and noted the huge achievement made by those resisting attempts to allow Mr Kabila to run for a third term.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe urged the international community to support the new leader, reminding the Council that for first time in nearly 60 years there would now be a transfer of power at the highest level.

A full breakdown of votes would be released if the Constitutional Court requested it, he said.

The court has never overturned results before, and some think most of its judges are close to the ruling party.

Mr Tshisekedi, the leader of largest opposition party which had faced repression at the hands of the Kabila regime, has denied the allegations of rigging.

If he is confirmed as the winner, he can be expected to be inaugurated on Tuesday 22 January.