DR Congo elections: Why do voters mistrust electronic voting?

Getty/JOHN WESSELS

Getty/JOHN WESSELSThe Democratic Republic of Congo is heading to the polls to elect a new president.

Current President Joseph Kabila is stepping down after 17 years and, as polling day nears, concerns about the running of the election in this vast country - nearly the size of Western Europe - are growing.

Earlier this month, a fire gutted one of the main electoral commission warehouses, destroying more than two-thirds of the electronic voting machines allocated for the capital Kinshasa.

The cause of the fire is unconfirmed.

Getty/JOHN WESSELS

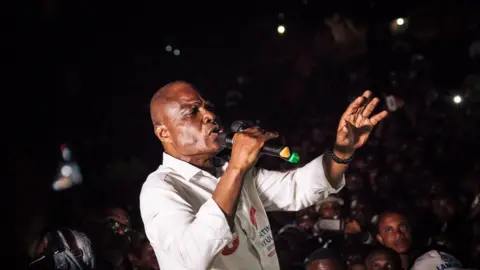

Getty/JOHN WESSELSThroughout the campaign, the use of these electronic voting machines for the first time has been a major source of contention.

Felix Tshisekedi, one of the opposition leaders vying for the presidency, has raised concerns about the e-voting machines. The other main opposition group, led by Martin Fayulu, has even threatened to boycott the poll.

The US ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, recently warned DR Congo against using electronic voting machines at a Security Council Meeting - and to stick with the "trusted, tested, transparent, and easy-to-use voting method" of paper ballots.

Getty/ALEXIS HUGUET

Getty/ALEXIS HUGUETWhy are voters concerned?

Elections in DR Congo have long been a logistical nightmare and previous elections have been marred by serious irregularities.

There are around 40 million eligible voters, with the electoral commission wiping nearly seven million from the original number - citing problems with people's registration details.

The election will feature 34,900 candidates for 500 national and 715 provincial seats and 21 presidential aspirants at 21,100 polling centres, across this huge and mostly rural country.

But in three areas, Beni, Butembo and Yumbi, the election has been postponed until March due to insecurity and an Ebola outbreak, a decision which has been met by a wave of protests.

The electoral commission plans to roll out at least 105,000 electronic voting machines, supplied by South Korean company Miru Systems.

Electronic voting machines similar to this one have been used in Belgium, Brazil, India, Namibia, and Venezuela.

But this is the first time this exact machine has been used, raising concerns that it is untried in an election scenario.

CENI

CENIHow e-voting works

Each voter enters the polling booth and makes a choice by selecting candidates on a tablet-like device.

This choice is printed on to a ballot paper, which is then submitted by the voter. It is these paper ballots that are then counted. The machines also keep an electronic tally to help verify the results.

The intention is that this both significantly simplifies the voting process and cuts costs.

If the tallies differ, there could well be disputes and confusion - although in such cases it should be the paper count that prevails, according to the electoral commission regulations.

Insufficient testing

Two separate studies have raised concerns over the e-voting system being adopted in the Congolese election.

A review of the device by the Westminster Foundation for Democracy says it has not been "thoroughly tested" and that there is a potential both for long delays and for misuse.

"There are some pretty serious security vulnerabilities," says Sarah Gardiner, analyst at the investigative group, The Sentry.

The manufacturer of the voting machines, Miru Systems, has responded to The Sentry's criticisms. "The security concerns raised are not real", wrote managing director Ken Cho in an email to the Washington Post.

These machines, he says, will bring "more transparency and accuracy" to the elections in DR Congo.

"The government has taken every necessary step to make sure the machine is secure," Phinees Muepu, the DR Congo's deputy ambassador to the UK told the BBC.

Getty/JOHN WESSELS

Getty/JOHN WESSELSWhere else has e-voting been used?

Data from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance identifies around 33 countries currently using some form of e-voting.

In some countries it has been used without controversy, there have been notable exceptions.

For elections in Venezuela last year, the head of the company which provided the machines - in this case Smartmatic - said the actual turnout had been inflated by at least one million votes.

This claim was rejected as baseless by the authorities, but the accusation will have increased fears about potential fraud using these systems.

There have also been concerns in Argentina. The country's senate rejected plans for e-voting in last year's elections, with issues raised over ballot secrecy and result manipulation.

And in parliamentary elections in Iraq earlier this year, a partial recount of votes was carried out following reports of technical glitches in electronic counting machines.

Potential for hacking

A common concern raised is that e-voting machines are vulnerable to security breaches in data networks.

These fears have been fanned by press reports of accusations of foreign political interference in elections in the United States and Europe. And while this may not be related to actual e-voting machines, the perception of election hacking remains.

There may not necessarily be a problem with e-voting as a system, but about the conditions in which it's implemented.

Nick Cheeseman, professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham, says what is needed is greater public trust in a demonstrably independent electoral commission and the politicians themselves.

He adds there should also be public education on how to use the machines.