Coronavirus vaccines: Will any countries get left out?

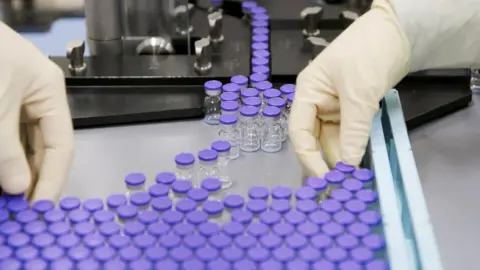

Reuters

ReutersHealth experts say the only solution to the coronavirus pandemic is a global one.

There have been more than 55 million cases of the virus confirmed around the world and more than 1.3 million deaths. Many hopes are pinned on a vaccine as a solution. But there are concerns that poorer nations could get left behind.

We have spoken to the experts about the main concerns that lie ahead and whether efforts to come up with a fair system will actually work.

The rush to buy in advance

Early results indicate that at least two vaccines are highly effective, several others have reached late-stage trials, and many more are at some stage of development.

None of these vaccines has been approved yet, but that hasn't stopped countries purchasing doses in advance.

A key research centre in the US - Duke University in North Carolina - is trying to keep tabs on all the deals being done. It estimates that 6.4 billion doses of potential vaccines have already been bought, and another 3.2 billion are either under negotiation or reserved as "optional expansions of existing deals".

The process of advance purchasing is well established in the pharmaceutical industry, as it can help to incentivise the development of products and fund trials, according to Clare Wenham, assistant professor of global health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

But it also means that whoever can pay the most at the earliest stage of production gets to the front of the queue, she says. And Duke's research found that the "vast majority" of vaccine doses that have been bought so far are going to high-income countries.

Some middle-income countries with manufacturing capacity have also been able to negotiate large purchase agreements as part of manufacturing deals. While other countries with the infrastructure to host clinical trials - such as Brazil and Mexico - have been able to use that as leverage in procuring future vaccines.

India's Serum Institute, for example, has committed to keeping half of all doses it produces for in-country distribution. Meanwhile, Indonesia is partnering with Chinese vaccine developers and Brazil is partnering with the trials run by the University of Oxford and pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca.

Because we do not yet know which vaccines will work, some countries are hedging their bets by purchasing multiple options. India, the EU, the US, Canada and the UK are among the countries which have reserved the most doses, according to the latest data.

The World Health Organization (WHO) told the BBC it was "understandable that leaders want to protect their own people first - they are accountable to their citizens - but the response to this global pandemic must be collective".

Delivering a limited supply to the world

Andrea Taylor, who has been leading the Duke analysis, said the combination of advance purchase agreements and limits on the number of doses that can be manufactured in the next couple of years meant "we're heading into a scenario where the rich countries will have vaccines and the poorer countries are unlikely to have access".

Experts note that we do not know yet how many vaccines might make it on to the market, or when they will become available. Deals are still being made, and questions remain about details of distribution.

According to Chandrakant Lahariya, co-author of the upcoming book Till We Win: India's Fight Against the Covid-19 Pandemic, availability in poorer countries could depend on how many vaccines are developed, how quickly and where they are manufactured.

"There are vaccines developed in India, and with our production capacity I foresee that the price could come down very quickly and availability in low- and middle-income countries will be very high."

Rachel Silverman, a policy analyst at the Center for Global Development think-tank in the US, said the most promising vaccines "are largely covered by advanced purchase agreements, mostly from wealthy countries".

"However, the big asterisk is that if there are many successful vaccines, there will be enough overall supply so that the wealthy countries would not necessarily exercise all their options."

Ms Silverman said recent announcements about some vaccines reaching more than 90% effectiveness - notably those from pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and Moderna - were "exceptional scientific news".

But she added: "There is very little likelihood that it will make it to low- and middle-income countries by the end of next year, at least in any significant numbers for mass vaccination."

Pfizer says it hopes to produce up to 50 million doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Each person needs two doses.

"Just doing the maths… you can see it's not enough to go around [from that alone]," Ms Silverman said.

However, she says now Moderna has also shown similarly promising results, there is more hope, as even more vaccines could follow.

The Moderna vaccine also has fewer requirements about cold storage, which has been a concern for poorer countries, particularly in warmer areas, and those with remote areas and limited electricity.

A new landmark distribution plan

Of course inequality in global health is nothing new. The WHO estimates that nearly 20 million infants have insufficient access to vaccines each year.

Research shows that during the 2009 "swine flu" pandemic the supply of vaccines was dominated by advance purchase agreements with wealthy states.

"We talk about the 90/10 divide in global health - 90% of the world's pharmaceutical products serve 10% of the world's population. This is part of that story," Ms Wenham said.

"But there's a difference between the fact that the market has loads and loads of erectile dysfunction drugs but no cures for Dengue fever... to us all now being in the same boat and us all facing exactly the same need for the same product, and that product being finite."

A landmark global vaccine plan known as Covax is seeking to ensure an equitable distribution of future coronavirus vaccines.

The joint initiative - between the Gavi vaccines alliance, the WHO and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) - aims to procure enough vaccines for participating countries to inoculate at least 20% of their populations.

The programme is designed so that richer countries buying vaccines agree to help finance access for poorer nations, too. So far, some 186 economies are involved.

Gavi says it has exceeded an initial target of raising more than $2bn (£1.5bn) to buy and distribute vaccines among 92 eligible countries which would otherwise be unable to afford them, but needs at least $5bn more in 2021.

Covax has already secured advance purchase agreements on hundreds of millions of doses of potential vaccines to be distributed equitably among countries. AstraZeneca, which is developing a vaccine with Oxford University, is part of the initiative.

CEO Pascal Soriot says the company's "objective is to enable every country around the world to get access more or less at the same time".

The company has said it will not profit from its vaccine "during the pandemic".

Pfizer has not signed up to Covax but told the BBC "there are discussions ongoing". The company said it was "committed to ensuring everyone has the opportunity" to access the vaccine, and had developed solutions to storage issues as its product need to be kept in ultra-low temperatures.

Moderna also hasn't made any deals to supply through Covax, but Gavi says talks are under way.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel said she was a "bit concerned" about the lack of deals on major vaccines.

She was speaking after leaders of the world's biggest economies - the G20 - pledged to ensure the affordable and fair distribution of coronavirus vaccines, so that poorer countries were not left out.

The countries doing side deals

Concerns have also been raised over the fact that several Covax signatories, including the UK and Canada, are directly negotiating their own deals with pharmaceutical companies.

"They're investing generously in Covax but at the same time they're undermining that by taking doses off the market when we know demand will outstrip supply," said Duke researcher Ms Taylor.

When asked if wealthy countries were undermining the spirit of the initiative, Gavi CEO Seth Berkley said it was a "complicated question".

"Every political leader wants to protect their own population, so in a sense that's what you would expect to happen. But in a pandemic of course we're only safe if we're all safe, so in that circumstance they need to be thinking about both of those issues," he said.

Human rights groups including Amnesty International and charities like Oxfam say more needs to be done to ensure global access to future vaccines. They have urged pharmaceutical companies to share information through the WHO's Covid-19 Technology Access Pool.

Reuters

Reuters"No single company can supply enough, and unless we tackle the problem with supply, we're going to have rich countries competing with poor countries and rich countries will always win," said Oxfam health policy adviser Anna Marriott.

"All of the vaccine manufacturers and the pharmaceutical corporations should pool their science and data, and commit to transferring their technology so that we can scale up production. No-one has come forward for that."

Policy analyst Ms Silverman said: "One way you can sometimes get rapid scale-up of health technologies for use in low- and middle-income countries is through licensing to generic manufacturers."

But she added: "This often gets into disputes about intellectual property and pricing and can be quite contentious."

While the scale of infections, deaths and restrictions varies in different countries, the WHO says any vaccine needs to be available in all countries to tackle the virus.

"With such a highly contagious virus, and in a globalised world, no country will be safe from the fallout of the pandemic until all countries are protected."