Coronavirus: How soon can we expect a working vaccine?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf or when scientists succeed in making a coronavirus vaccine, there won't be enough to go around.

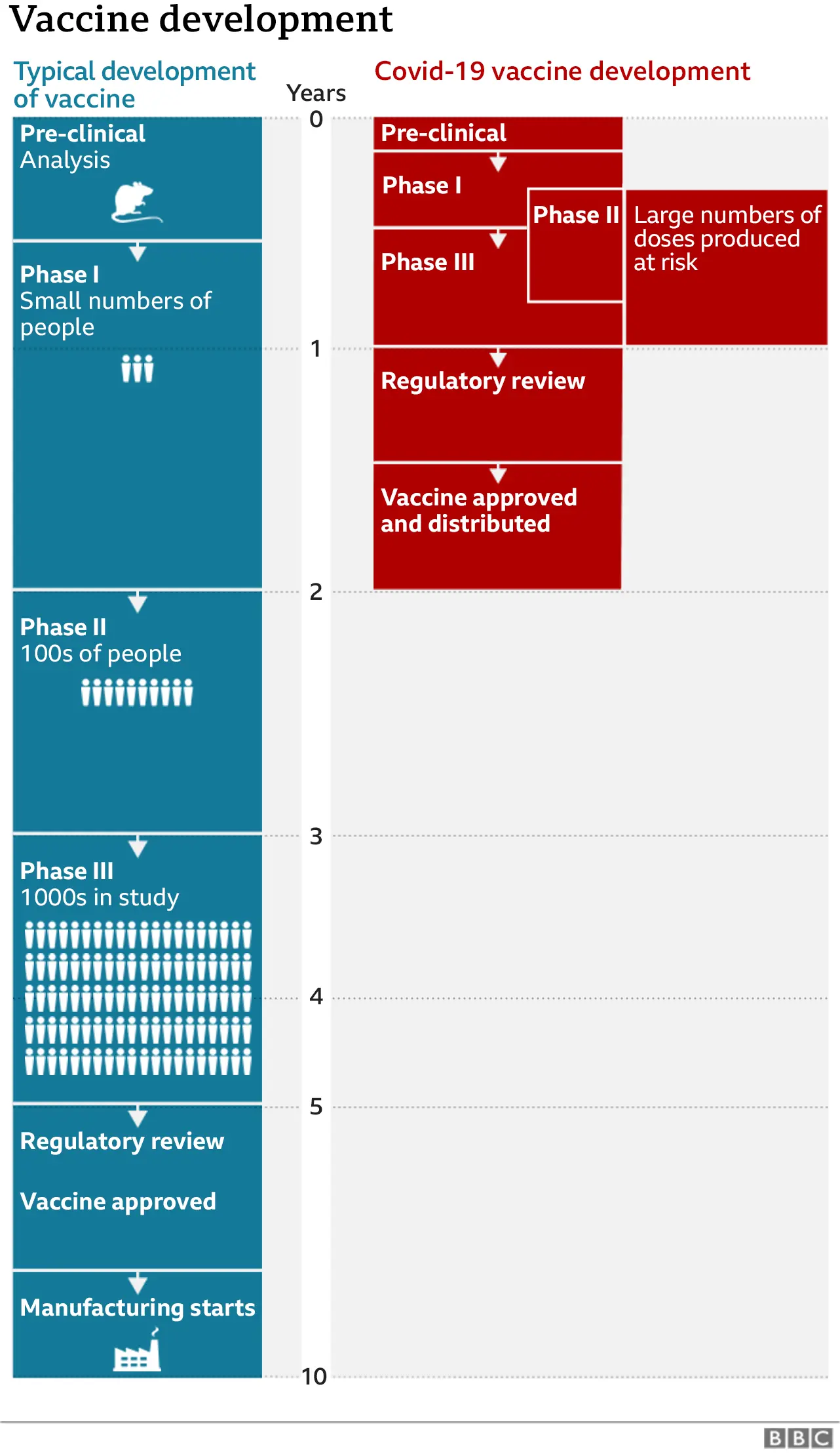

Research labs and pharmaceutical companies are rewriting the rulebook on the time it takes to develop, test and manufacture an effective vaccine.

Unprecedented steps are being taken to ensure roll-out of the vaccine is global. But there are concerns that the race to get one will be won by the richest countries, at the expense of the most vulnerable.

So who will get it first, how much will it cost and, in a global crisis, how do we make sure nobody gets left behind?

Vaccines to fight infectious diseases usually take years to develop, test and deliver. Even then, their success is not guaranteed.

To date, only one human infectious disease has been totally eradicated - smallpox - and that took 200 years.

The rest - from polio to tetanus, measles, mumps and TB - we live with, or without, thanks to vaccinations.

How soon can we expect a coronavirus vaccine?

Reuters

ReutersTrials involving thousands of people are already under way to see which vaccine can protect against Covid-19, the respiratory disease caused by coronavirus.

A process that usually takes five to 10 years, from research to delivery, is being pared down to months. In the meantime, manufacturing is being scaled up - with investors and manufacturers risking billions of dollars to be ready to produce an effective vaccine.

Russia says trials of its Sputnik-V vaccine have shown signs of immune response in patients and has rolled out the vaccine for public use while late-stage trials continue. China says it has developed a successful vaccine that is being made available to its military personnel. But concerns have been raised about the speed at which both vaccines have been produced.

Neither are on the World Health Organization's list of vaccines that have reached phase three clinical trials - the stage that involves more widespread testing in humans.

Some of these leading candidates hope to get their vaccine approved by the end of the year - although the WHO has said it does not expect to see widespread vaccinations against Covid-19 until the middle of 2021.

Pfizer and BioNTech say preliminary analysis shows their vaccine can prevent more than 90% of people from getting Covid-19. They plan to apply for emergency approval to use the vaccine by the end of November.

Pfizer believes it will be able to supply 50 million doses by the end of this year, and around 1.3 billion by the end of 2021.

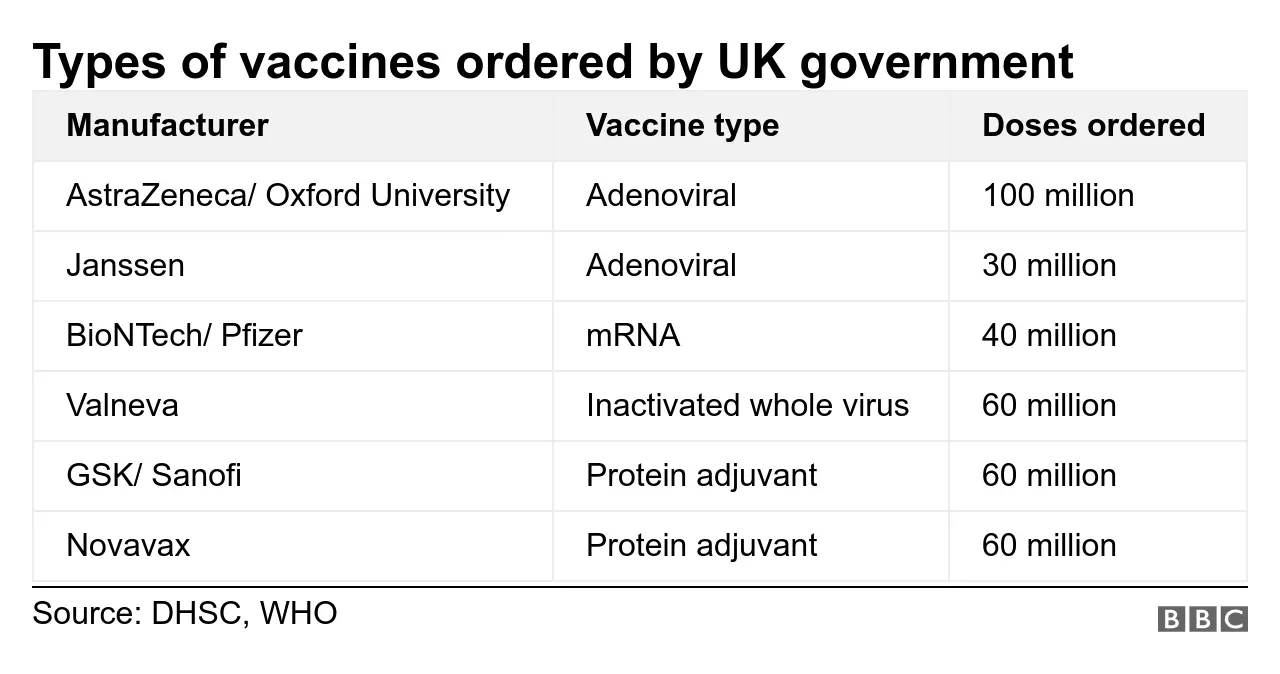

British drug manufacturer AstraZeneca, which has the licence for the Oxford University vaccine, is ramping up its global manufacturing capacity and has agreed to supply 100 million doses to the UK alone and possibly two billion globally - should it prove successful.

There are dozens of other pharmaceutical companies with clinical trials under way.

Not all of them will succeed - normally only about 10% of vaccine trials are successful. The hope is that the global focus, new alliances, and common purpose will raise the odds this time.

But even if one of these vaccines is successful, the immediate shortfall is clear.

Preventing vaccine nationalism

Governments are hedging their bets to secure potential vaccines, making deals for millions of doses with a range of candidates before anything has been officially certified or approved.

The UK government, for example, has signed deals for undisclosed sums for six potential coronavirus vaccines that may or may not prove successful.

The US hopes to get 300 million doses by January from its investment programme to fast-track a successful vaccine.

But not all countries are in a position to do likewise.

Organisations such the Medecins Sans Frontieres, often on the frontline delivering vaccines, say locking in advanced deals with pharmaceutical companies creates "a dangerous trend of vaccine nationalism by richer nations".

This in turn reduces global stocks available to the vulnerable in poorer countries.

In the past, the price of life-saving vaccines has left countries struggling to fully immunise children against diseases such as meningitis, for example.

Dr Mariângela Simão, the WHO's assistant director-general responsible for access to medicines and health products, says we need to ensure vaccine nationalism is held in check.

"The challenge will be to ensure equitable access - that all countries have access, not just those who can pay more."

Is there a global vaccine task force?

The WHO is working with the epidemic response group, Cepi, and the Vaccine Alliance of governments and organisations, known as Gavi, to try to level the playing field.

At least 94 rich nations and economies, so far, have signed up to the global vaccine plan known as Covax, which aims to raise $2bn (£1.52bn) by the end of 2020 to help buy and fairly distribute a drug worldwide. The US, which wants to leave the WHO, is not one of them.

By pooling resources in Covax, participants hope to guarantee 92 lower income countries, in Africa, Asia and Latin America, also get "rapid, fair and equitable access" to Covid-19 vaccines.

The facility is helping to fund a range of vaccine research and development work, and supporting manufacturers in scaling up production, where needed.

Having a wide portfolio of vaccine trials signed up to their programme, they are hoping at least one will be successful so they can deliver two billion doses of safe, effective vaccines by the end of 2021.

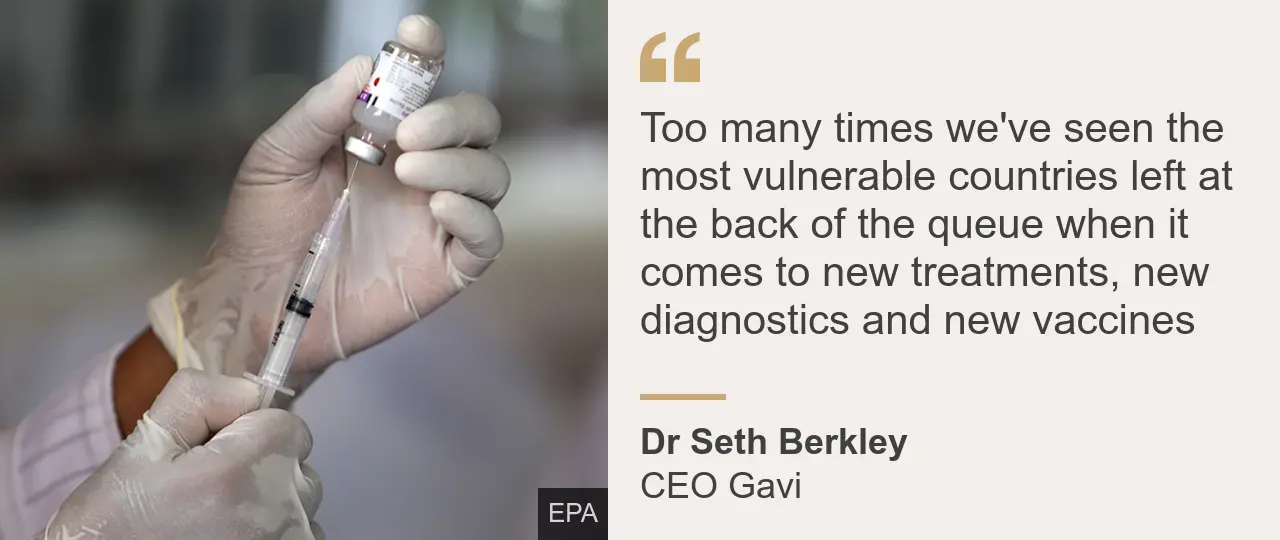

"With COVID-19 vaccines we want things to be different," says Gavi's CEO Dr Seth Berkley. "If only the wealthiest countries in the world are protected, then international trade, commerce and society as a whole will continue to be hit hard as the pandemic continues to rage across the globe."

How much will it cost?

While billions of dollars are being invested in vaccine development, millions more are being pledged to buy and supply the vaccine.

Prices per dose depend on the type of vaccine, the manufacturer and the number of doses ordered. Pharmaceutical company Moderna, for example, is reportedly selling access to its potential vaccine at between $32 and $37 a dose (£24 to £28).

AstraZeneca, on the other hand has said it will supply its vaccine "at cost" - or a few dollars per dose - during the pandemic.

The Serum Institute of India (SSI), the world's largest vaccine manufacturer by volume, is being backed by $150m from Gavi and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to make and deliver up to 100 million doses of the successful Covid-19 vaccines for India and low- and middle-income countries. They say the ceiling price will be $3 (£2.28) a dose.

But patients receiving the vaccine are unlikely to be charged in most cases.

In the UK, mass distribution will be via the NHS health service. Student doctors and nurses, dentists and vets could be trained to back up existing NHS staff in administering the jab en masse. Consultation is currently under way.

Other countries, such as Australia, have said they will offer free doses to their population.

People receiving vaccines via humanitarian organisations - a vital cog in the global distribution wheel - will not be charged.

In the US, while the shot might be free, healthcare professionals could charge for administering the jab - leaving uninsured Americans possibly facing a vaccine bill.

So who gets it first?

Although the pharmaceutical companies will be making the vaccine, they won't be the ones who decide who gets vaccinated first.

EPA

EPA"Each organisation or country will have to determine who it immunises first and how it does that," Sir Mene Pangalos - AstraZeneca's Executive Vice President told the BBC.

As the initial supply will be limited, reducing deaths and protecting health care systems are likely to be prioritised.

The Gavi plan is that countries signed up to Covax, high or low income alike, will receive enough doses for 3% of their population - which would be enough to cover health and social care workers.

As more vaccine is produced, allocation is increased to cover 20% of the population - this time prioritising over 65s and other vulnerable groups.

After everybody has received 20%, the vaccine would be distributed according to other criteria, such as country vulnerability and immediate threat of Covid-19.

Negotiations are still under way for many other elements of the allocation process.

"The only certainty is that there won't be enough - the rest is still up in the air," says Dr Simao.

Gavi insists richer participants can request enough doses to vaccinate between 10-50% of their population, but no country will receive enough doses to vaccinate more than 20% until all countries in the group have been offered this amount.

Dr Berkley says a small buffer of about 5% of the total number of available doses will be kept aside, "to build a stockpile to help with acute outbreaks and to support humanitarian organisations, for example to vaccinate refugees who may not otherwise have access".

How do you distribute a global vaccine?

Markel Redondo/ MSF

Markel Redondo/ MSFA lot depends on which vaccine is successful.

The ideal vaccine has a lot to live up to. It needs to be affordable. It needs to generate strong, long-lasting immunity. It needs a simple refrigerated distribution system and manufacturers must be able to scale-up production rapidly.

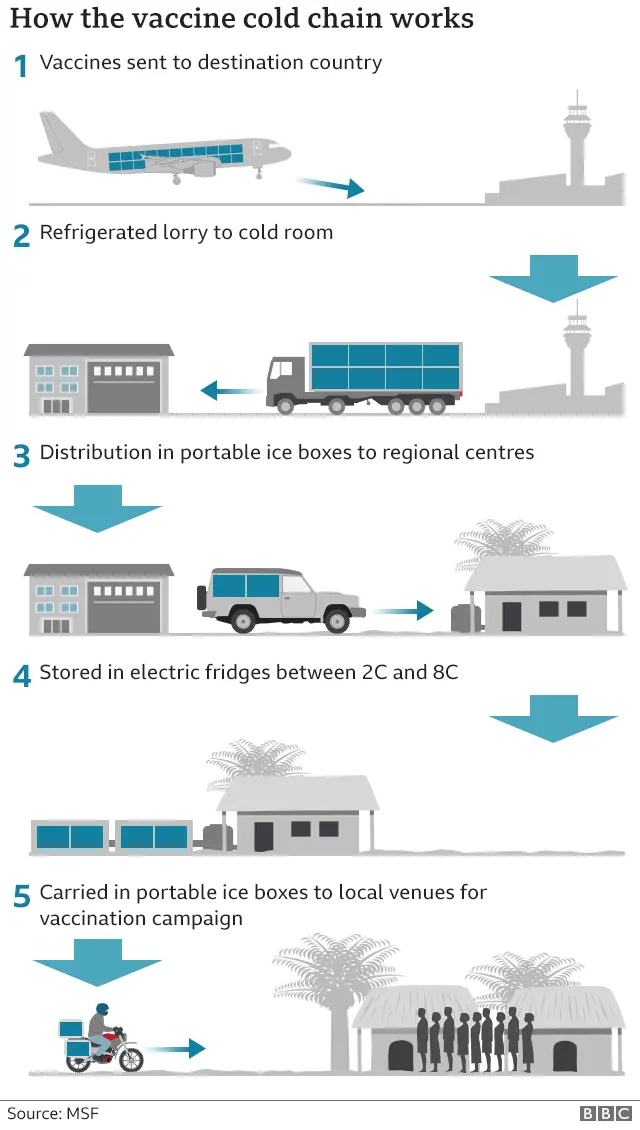

The WHO, UNICEF and Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF / Doctors Without Borders), already have effective vaccination programmes in place around the world with the so called "cold chain" facilities - cooler trucks and solar fridges to keep vaccines at the right temperature as they travel from factory to field.

But adding a new vaccine to the mix could pose huge logistical problems for those already facing a difficult environment.

Vaccines usually need to be kept refrigerated - usually between 2C and 8C.

That's not too much of a challenge in most developed countries, but can be an "immense task" where infrastructure is weak and electricity supply and refrigeration unstable.

"Maintaining vaccines under cold chain is already one of the biggest challenges' countries face and this will be exacerbated with the introduction of a new vaccine," MSF medical adviser Barbara Saitta told the BBC.

"You will need to add more cold chain equipment, make sure you always have fuel (to run freezer and refrigerators in absence of electricity) and repair/replace them when they break and transport them wherever you need them."

AstraZeneca has suggested their vaccine would need the regular cold chain between 2C and 8C.

But at present it looks like the Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine would need ultra-cold chain - storage at -80C before being distributed.

Welcoming the Pfizer announcement, Dr Richard Hatchett, of Cepi acknowledged that would "remain a challenge for use in some settings".

"This is something which will have to be addressed if the vaccine is to be made broadly available," he said.

But the Ebola vaccine also needed very low temperatures, so it is not impossible.

"To keep the Ebola vaccine at -60°C or colder we had to use a special cold chain equipment to store and transport them, plus we had to train staff to use all this new equipment," said Barbara Saitta.

There is also the question of the target population. Vaccination programmes usually target children, so agencies will have to plan how to reach people that normally are not part of the immunization program.

As the world waits for the scientists to do their bit, many more challenges await. And vaccines are not the only weapon against coronavirus.

"Vaccines are not the only solution," Says Dr Simao, of the WHO. "You need to have diagnostics. You need to have a way to decrease mortality, so you need therapeutics, and you need a vaccine.

"Besides that, you need everything else - social distancing, avoiding crowded places and so on."

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

- ENDGAME: When will life get back to normal?

- EASY STEPS: What can I do?

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash