Who is responsible for helping out migrants at sea?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMatteo Salvini, Italy's Interior Minister until last September, took a tough line with boats that had rescued migrants in the Mediterranean.

Mr Salvini, a right-wing populist, blocked vessels from entering Italian ports when he was in office.

But he's now facing a possible trial in Italy for preventing rescued migrants being landed on his country's shores.

Are we or are we not a sovereign country, free to protect its borders and its beaches?

So are there laws around helping out migrants who get into difficulty at sea, and how are they meant to be applied?

Do you have to rescue people at sea?

International maritime rules are clear that vessels at sea have a duty to rescue those in trouble.

The 1974 Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea says any ship learning of persons in distress "should proceed with all speed to their assistance".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere's also the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea which makes clear that any state with a ship flying its flag should ensure that ship goes to rescue those "in distress."

There also established legal frameworks for how different countries should co-ordinate rescue efforts between them in the open sea.

Who should carry out rescue operations?

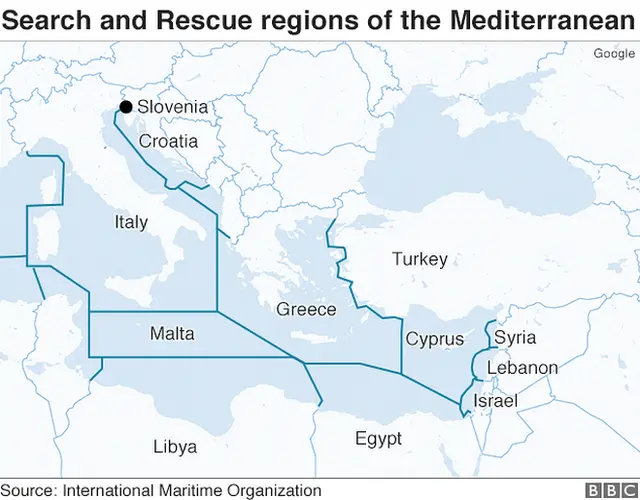

The Mediterranean is divided up into search and rescue zones, with each state responsible for co-ordinating operations in its zone.

There's also an EU-wide border and coastguard agency called Frontex, but that is more focused on detecting smuggling and terror-related activity along Europe's borders.

However, Frontex has told the BBC it does carry out rescue operations when asked to, and would go outside their normal zone of operations if necessary.

The EU set up a naval operation in 2015 known as Operation Sophia to disrupt people smuggling networks, which also helped rescue migrants who got into trouble at sea.

Private rescue vessels operated and funded by non-governmental organisations, charities and others have also helped rescue migrants, particularly off the coast of Libya where political instability and the lack of a central authority meant there has been no-one to co-ordinate rescue efforts.

However, the EU has been funding various schemes in Libya in recent years to improve its border security operations, like training up the Libyan coastguard so they pick up people who set off to sea.

What's meant to happen to those rescued?

According to the International Maritime Organization, which helped put together some of the principles behind rescue at sea, member states have a duty "to co-ordinate so that persons rescued at sea are disembarked in a place of safety as soon as possible".

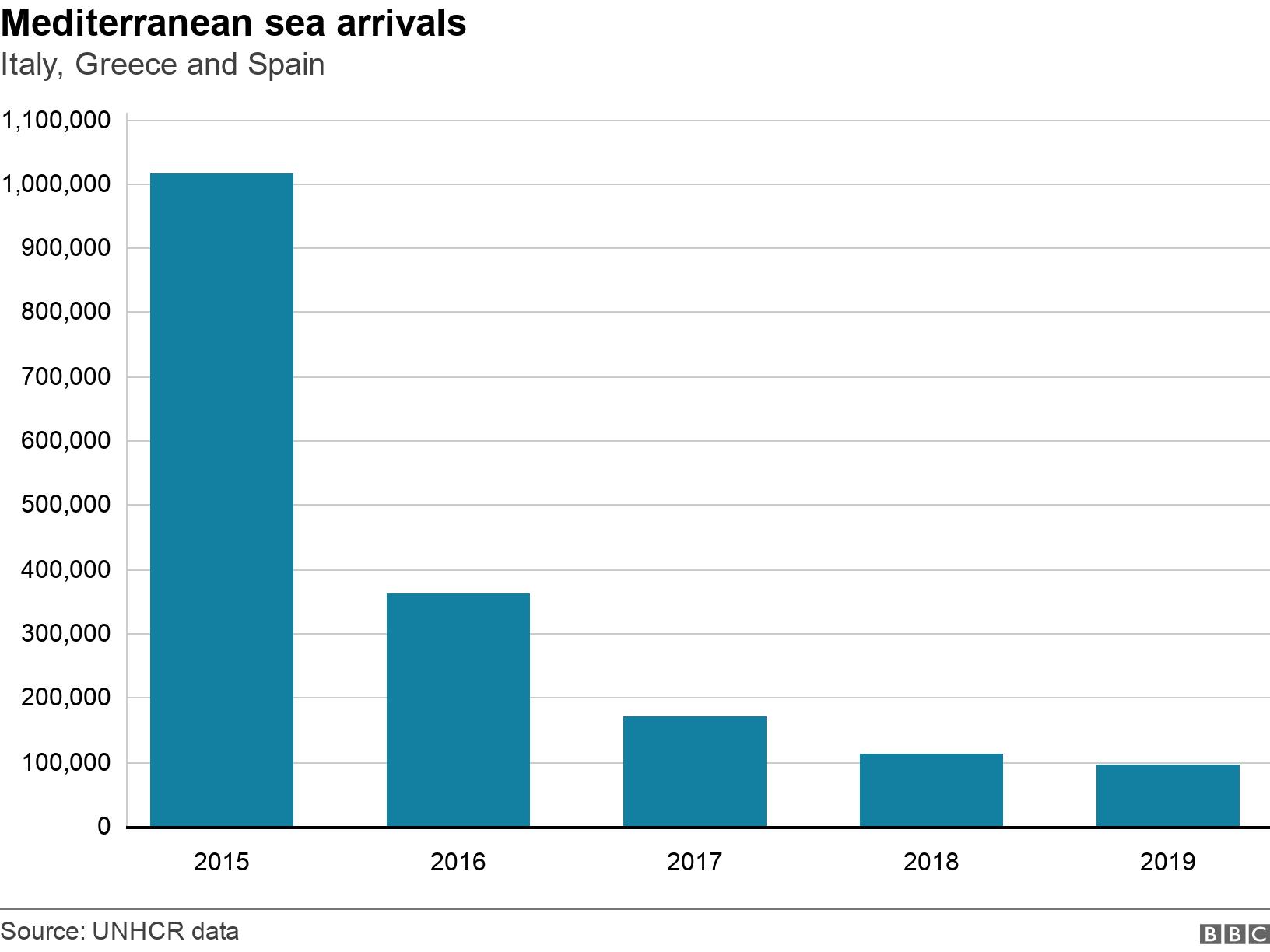

This can be open to interpretation, something which became clear as the numbers of migrants trying to reach Europe by sea grew after 2014, before gradually falling.

"There is no obligation on a state responsible for a specific search and rescue area, or responsible for co-ordinating a rescue effort, to receive the survivors on land," says Ainhoa Campas Velasco of the Institute of Maritime Law at University of Southampton.

But she adds that humanitarian considerations are meant to form part of search and rescue operations, although states are allowed to refuse permission for vessels to enter their territorial waters.

In June 2018, the rescue vessel Aquarius - operated by charities - was carrying more than 600 people when it was blocked from docking by both Malta and Italy.

In June 2019, the Sea-Watch 3 rescue vessel, captained by Carola Rackete, defied Italian orders not to dock in the island of Lampedusa with some 40 migrants. Ms Rackete was arrested.

She argued she had a duty under humanitarian law to land because of the worsening condition of those on board her boat. An Italian judge sided with her reading of the law, and freed her.

But under Mr Salvini, Italy continued to block vessels - including its own coastguard ships - from docking in its ports until and unless other EU states agreed to take the migrants on board.

Is there a system for taking in migrants?

At the moment, it is very ad hoc.

There are rules which say refugees should apply for asylum in the first country of entry to the EU. But these have been strongly criticised by Italy and Greece, who say it's unfair because it means they have to shoulder the overwhelming burden of those arriving by sea.

President Macron of France has called for a new system for distributing migrants across the EU.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, other EU members have been reluctant to agree a system of quotas for more migrants.

EU efforts - led by Italy - to get Libya to intercept and return migrants before they reach European waters have been strongly criticised by human rights groups.

Last year, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said Italy had breached human rights obligations by encouraging Libya's coastguard to return migrants to detention centres, where they suffered serious abuse and torture.