Stranded migrants: Macron scolds Italy over Aquarius ship

French President Emmanuel Macron has accused the Italian government of "cynicism and irresponsibility" for refusing to let a stranded rescue ship packed with migrants dock in Italy.

A charity looking after the 629 migrants on the Aquarius, stranded off Malta, says two Italian ships will help take them to Spain's port of Valencia.

Spain is some three days' sailing away.

Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte hit back angrily at France, calling its stance on migrants "hypocritical".

He criticised "countries that have always preferred to turn their backs when it comes to immigration".

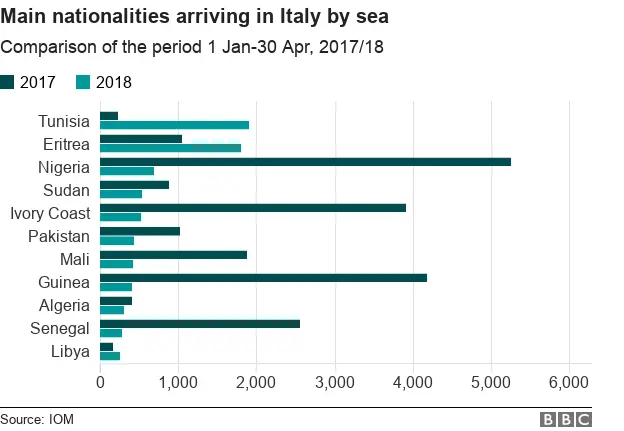

In the past five years Italy has taken in more than 640,000 mainly African migrants and says its EU partners must ease the burden.

Most migrants who survive the perilous voyages from North Africa end up in overcrowded Italian camps. Among them are refugees fleeing war and persecution, who have a right to asylum.

The Aquarius migrants, mainly sub-Saharan Africans, were picked up off Libya's coast at the weekend.

They were found in inflatable boats and are now being looked after by Doctors without Borders (MSF) and the Franco-German charity SOS Méditerranée aboard the Aquarius.

Mr Macron's spokesman Benjamin Griveaux said the French president recalled that "in cases of distress, those with the nearest coastline have a responsibility to respond".

"There is a degree of cynicism and irresponsibility in the Italian government's behaviour," he quoted President Macron as saying.

The plan is for the Aquarius to be joined by an Italian coastguard ship and a warship, then for all three to head for Valencia.

The coastguard ship Dattilo and the warship are expected to take migrants on board from the Aquarius in the coming hours. There are medics and UN Children's Fund (Unicef) workers on the Dattilo.

SOS Méditerranée tweeted photos of fresh supplies arriving on board on Tuesday.

Allow X content?

Earlier the crew said the ship could not sail to Spain while it was overcrowded, and conditions at sea were deteriorating.

Among the migrants are seven pregnant women, 11 young children and 123 unaccompanied minors.

The minors are aged between 13 and 17 and come from Eritrea, Ghana, Nigeria and Sudan, according to a journalist on the ship, Anelise Borges.

Fifteen migrants have serious chemical burns and several suffered hypothermia, according to MSF.

AFP

AFPItaly defiant

Italian Deputy Prime Minister Luigi Di Maio shrugged off the French criticism. "I'm glad the French have discovered responsibility: if they want, we will help them," he said. "Let them open their ports and we will transfer a few of the people to France."

Earlier, Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini defended his refusal to let the ship dock, saying: "Saving lives is a duty, turning Italy into a huge refugee camp is not." Instead he urged Malta to receive the migrants.

His right-wing League party is in a new populist government which has pledged to stop the migrant influx to Italy and deport failed asylum seekers.

However, the Italian coastguard ship Diciotti is currently taking 937 migrants to the Sicilian port of Catania. They were picked up not by charities but by the EU naval rescue mission off Libya.

Spain's Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, who took office a week ago, said he would give "safe harbour" to the Aquarius, after Italy and Malta had refused.

The nationalist authorities on the French island of Corsica also offered to receive the Aquarius, before the latest plan involving Italian ships was announced.

Aid worker Aloys Vimard, also on board, told the BBC the migrants were afraid they would be returned to Libya.

What is the law on accepting ships?

Rules on disembarking and assisting rescue ships such as Aquarius are governed by international law.

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea dictates that any ship learning of distress at sea must assist regardless of the circumstances.

It says that the country responsible for operations in that area has primary responsibility for taking them from the ship.

It also clearly states that the relevant government "shall arrange for such disembarkation to be effected as soon as reasonably practicable".

A big question for Spain: What happens to the next ship?

By Kevin Connolly, Europe correspondent, BBC News

The EU wrote its rules about how migrants should be handled in the 1990s, when no-one could have imagined the collapse of Libya would create huge flows of desperate people heading across the Mediterranean from sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

The rules say migrants are the responsibility of the first member state where they land - an overwhelming problem in countries like Greece and Italy, where the election of a populist government is at least in part a response to the pressure.

And when Matteo Salvini proclaims "victory", he's telling his voters that the promise of a tougher line on immigration is real.

He is challenging the EU to find a proper solution too, based on forcing other member states to accept quotas of migrants - something it has failed to do so far. And he's incidentally created a big question for Spain. Will its offer to the Aquarius be extended to more ships in the future?