Heart health: Cure hope for inherited condition HCM

BBC

BBCA 28-year-old man with an inherited heart condition hopes research can stop him from passing it to any children he might have.

Elis Power from Tondu, Bridgend, has hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), which can cause sudden cardiac arrest.

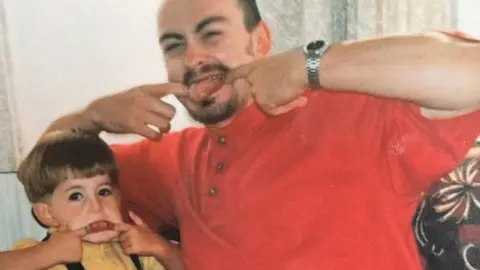

He was three when his father Ray died from the condition at the age of 30.

The British Heart Foundation (BHF) is funding £30m research into an "injectable cure", which could be ready for trial in five years.

It hopes will prevent others from developing the condition.

BHF Cymru said as many as 13,000 people are believed to be affected by inherited heart muscle diseases in Wales.

Elis said of his father: "He was an avid runner and rugby player, didn't drink and didn't smoke. All the things you should do to keep yourself healthy, but unfortunately it didn't stop it because it's genetic.

"He was undiagnosed with the condition," he added. "We only found out post-mortem that was the cause."

Family Photo

Family PhotoHCM means that some of the heart muscle is enlarged which can lead to abnormal heart rhythm and obstructions.

Elis was 22 when he was found to have the gene that causes HCM. But he said the fear that he would have the condition also affected his childhood

'I have struggled mentally'

"I had to give up rugby at a young age and went back and forward to hospitals," he explained. "I consider myself fortunate that I don't have too many physical symptoms but I have struggled mentally over the years.

"Also when it comes to family, I recently got married and the thought of passing that gene on, it's mentally straining."

Medication and regular check-ups have been part of Elis's life since he was a child.

He now has a defibrillator implanted under his skin, but one of his main concerns is passing the gene on to future generations.

"It's passing on the gene and my children having to go through the same things I have," he said. "Going to London for hospital appointments every six months, not being able to do certain things like football or rugby. They couldn't potentially live life the way they wanted to.

"They would be told what they can and can't do like I have. There's always the risk of them suffering more physically than I have. If I was to have a child, it's 50:50 whether or not they get the gene"

Elis's wife Jasmine is also concerned about how the condition might affect any future decisions about having children.

"It does worry me a little bit about potentially passing it on the condition to children when we decide to start a family in the future," she said, "but there are other options available too so we don't have to conceive naturally and pass the gene on to our children".

'Once in a generation opportunity'

The BHF has awarded a £30m grant to Cureheart, an international team of researchers who have said they are five years from clinical trials of a treatment that could stop the faulty gene from damaging the heart.

"This is our once in a generation opportunity to relieve families of the constant worry of sudden death, heart failure and the potential need for a heart transplant," said lead researcher Prof Hugh Watkins from The Radcliffe Department of Medicine at Oxford University

"After 30 years of research, we have discovered many of the genes and specific genetic faults responsible for different cardiomyopathies, and how they work," he added. "We believe that we will have a gene therapy ready to start testing in clinical trials in the next five years."

Elis said: "It's huge news, especially for people in my situation and for families that have been affected by cardiomyopathy because a potential cure is something you always dream of if you have a chronic condition.

He said he would be less worried about passing on the condition if "you have potentially much better treatment options and a potential cure for a condition that could stop it further down the line".

"It could stop with me and future generations and other people's families could basically be unaffected in the future," he said.