Human embryos edited to stop disease

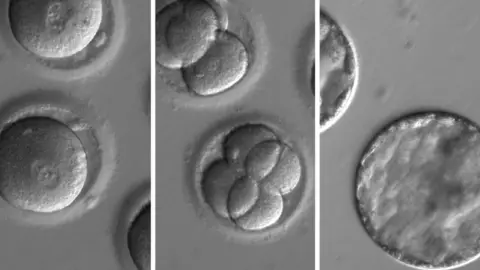

OHSU

OHSUScientists have, for the first time, successfully freed embryos of a piece of faulty DNA that causes deadly heart disease to run in families.

It potentially opens the door to preventing 10,000 disorders that are passed down the generations.

The US and South Korean team allowed the embryos to develop for five days before stopping the experiment.

The study hints at the future of medicine, but also provokes deep questions about what is morally right.

Science is going through a golden age in editing DNA thanks to a new technology called Crispr, named breakthrough of the year in just 2015.

Its applications in medicine are vast and include the idea of wiping out genetic faults that cause diseases from cystic fibrosis to breast cancer.

Heart stopper

US teams at Oregon Health and Science University and the Salk Institute along with the Institute for Basic Science in South Korea focused on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

The disorder is common, affecting one in every 500 people, and can lead to the heart suddenly stopping beating.

It is caused by an error in a single gene (an instruction in the DNA), and anyone carrying it has a 50-50 chance of passing it on to their children.

In the study, described in the journal Nature, the genetic repair happened during conception.

Sperm from a man with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was injected into healthy donated eggs alongside Crispr technology to correct the defect.

It did not work all the time, but 72% of embryos were free from disease-causing mutations.

Eternal benefit

Dr Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a key figure in the research team, said: "Every generation on would carry this repair because we've removed the disease-causing gene variant from that family's lineage.

"By using this technique, it's possible to reduce the burden of this heritable disease on the family and eventually the human population."

There have been multiple attempts before, including, in 2015, teams in China using Crispr-technology to correct defects that lead to blood disorders.

But they could not correct every cell, so the embryo was a "mosaic" of healthy and diseased cells.

Their approach also led to other parts of the genetic code becoming mutated.

Those technical obstacles have been overcome in the latest research.

However, this is not about to become routine practice.

The biggest question is one of safety, and that can be answered only by far more extensive research.

There are also questions about when it would be worth doing - embryos can already be screened for disease through pre-implantation genetic diagnosis.

However, there are about 10,000 genetic disorders that are caused by a single mutation and could, in theory, be repaired with the same technology.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, from the Francis Crick Institute, told the BBC: "A method of being able to avoid having affected children passing on the affected gene could be really very important for those families.

"In terms of when, definitely not yet. It's going to be quite a while before we know that it's going to be safe."

Nicole Mowbray lives with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and has a defibrillator implanted in her chest in case her heart stops.

But she is unsure whether she would ever consider gene editing: "I wouldn't want to pass on something that caused my child to have a limited or painful life.

"That does come to the front of my mind when I think about having children.

"But I wouldn't want to create the 'perfect' child, I feel like my condition makes me, me."

Ethical?

Darren Griffin, a professor of genetics at the University of Kent, said: "Perhaps the biggest question, and probably the one that will be debated the most, is whether we should be physically altering the genes of an IVF embryo at all.

"This is not a straightforward question... equally, the debate on how morally acceptable it is not to act when we have the technology to prevent these life-threatening diseases must also come into play."

The study has already been condemned by Dr David King, from the campaign group Human Genetics Alert, which described the research as "irresponsible" and a "race for first genetically modified baby".

Dr Yalda Jamshidi, a reader in genomic medicine at St George's University of London, said: "The study is the first to show successful and efficient correction of a disease-causing mutation in early stage human embryos with gene editing.

"Whilst we are just beginning to understand the complexity of genetic disease, gene-editing will likely become acceptable when its potential benefits, both to individuals and to the broader society, exceeds its risks."

The method does not currently fuel concerns about the extreme end of "designer babies" engineered to have new advantageous traits.

The way Crispr is designed should lead to a new piece of engineered DNA being inserted into the genetic code.

However, in a complete surprise to the researchers, this did not happen.

Instead, Crispr damaged the mutated gene in the father's sperm, leading to a healthy version being copied over from the mother's egg.

This means the technology, for now, works only when there is a healthy version from one of the parents.

Prof Lovell-Badge added: "The possibility of producing designer babies, which is unjustified in any case, is now even further away."

Follow James on Twitter.