Incurable breast cancer: Drug gives patients more time, study finds

CIPhotos/Getty Images

CIPhotos/Getty ImagesMillions could benefit after research into a new treatment for women with incurable breast cancer yielded "astonishing results".

The Welsh-led study saw women with a genetic abnormality in their cancer given a new drug combined with hormone therapy.

It found they could expect to survive almost twice as long compared with those given standard treatment.

Prof Rob Jones said the treatment could give people more time with loved ones.

The results have been presented at the world's biggest cancer conference in Chicago and have been published in the Lancet Oncology journal.

The research showed women who have a common genetic abnormality in their cancers could expect to survive almost twice as long after being given capivasertib than those given the standard treatment alone.

The study's co-lead, Prof Rob Jones, of Velindre Cancer Centre and Cardiff University, said: "There has never been a trial targeting this genetic pathway in breast cancer that has an overall survival advantage like this - it's really quite extraordinary.

"When a patient is diagnosed with metastatic cancer [a cancer that has spread], the most important question for the patient is 'how long have I got? Am I going to see my grandchildren grow up?'

"We're not able to offer a cure - but we are buying people additional really important time they can spend with their families and friends."

What is breast cancer?

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK and accounts for 15% of all cancers and 30% of cancers in females.

The latest figures (2016-18) showed 8,353 women in Wales were diagnosed with breast cancer over a three-year period.

This equates to 176 cases per 100,000 women, a rise from 156 cases per 100,000 in the three years to 2003.

When diagnosed at its earliest stage, almost all (98%) people with breast cancer will survive the disease for five years or more, compared with about one in four (26%) people when the disease is diagnosed at the latest stage.

Former post-mistress Farhana Badat, from Newport, found out she had breast cancer after attending her first mammogram aged 50.

The now 59-year-old had part of her breast removed, and later began hormone treatment, but in August 2016 she was told the cancer had spread to the bones of her ribs and spine.

"I thought I'd gone into remission and that I was progressing as much as possible," she said.

"But unfortunately it wasn't meant to be, I think it affects the family a lot, they feel helpless- it was a very emotional time for us all."

Farhana Badat

Farhana BadatShortly after, she was invited to take part in the clinical trial at Velindre Cancer Centre.

Farhana goes to Velindre for regular check-ups and is feeling well. She said she was proud to have taken part in research that could help extend the lives of others with incurable breast cancer.

"It makes you feel really good. I'm not a great runner, I'm not a great baker, and you think 'how do you support the people that have supported you so well?'

"This is one way I have supported them, and I hope the drug will be available to the larger public and be made available on the NHS.

"My eldest grandchild is seven, and the youngest is 10 months old, I've enjoyed every moment with them and you begin to realise how much you can enjoy, you have to live every moment as best you can."

What did the trial investigate?

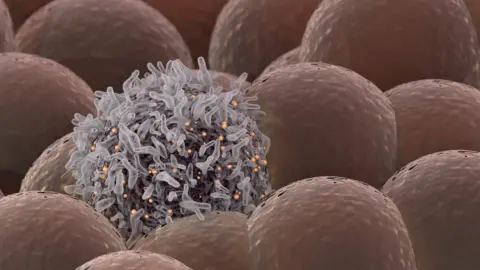

Breast cancer cells have receptors, which hormones attach to and which allow the tumour to grow.

Cancer involving the hormone oestrogen is called oestrogen-receptor positive, or ER positive breast cancer.

This accounts for about 70-80% of the 56,000 new breast cancer cases in the UK each year.

For patients who are diagnosed with incurable cancer, hormone treatment can help, but often patients become resistant to it.

One particular protein, AKT, is known to drive this resistance.

The FAKTION trial has been evaluating to what extent the new drug Capivaertib, which inhibits AKT activity, can improve the outlook for patients when combined with the hormone treatment Fulverstant.

A total of 140 patients from 19 hospitals took part in the trial, which is being led by Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, and the Christie Hospital in Manchester, along with Cardiff and Manchester universities.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe results showed patients with some common mutations in their cancer, 55% of women on the trial, could expect to live for 39 months after being given the drug, compared with 20 months for those in the control group, given the hormone and a placebo.

They also showed women without one of these mutations did not see a significant increase in survival, meaning the therapy can be targeted at those most likely to benefit.

Prof Jones said: "What we always want to do with cancer patients is to give them the treatment that suits them best.

"We're moving more and more towards genomic profiling, working out which patients will benefit, and this trial has been very successful in picking out those patients."

He added that the 55% of women that did see a benefit equated to potentially tens of millions of people worldwide.

The latest research builds on results published in 2019, and a large scale phase three clinical trial into the treatment, involving about 800 patients from across the world is now under way.

If that is successful, then it could pave the way for Capivasertib, developed by AstraZeneca, to become a standard treatment.

Interpreting a cancer's genetic code

The research highlights the growing importance of understanding how the genetic code of cancer can influence what treatments might work best.

Wales is the only country to send tissue samples from all patients newly diagnosed with cancer that has spread for genetic testing.

By interpreting what genetic mistakes or mutations are at play, this can help determine how the cancer might develop and what treatments might work best, meaning therapy can be increasingly tailored or personalised for the individual.

Dr Helen Roberts, head of the Solid Tumour Service at the All Wales Medical Genomics Service (AWMGS), said: "One drug is not necessarily the best treatment for all patients with a particular cancer type, so we're looking at how genetic code can be a driver.

"It can be cash saving, we want to use drugs where they are going to work and we don't want to give somebody something that has no effect - so it's a double win really.

"We have the technology and experience now to decide how to treatment people as individuals, and think what's going to work best for you."