Ambulances: The paramedics keeping patients out of hospital

Chest pains for a 63-year-old man might typically mean a hospital trip to check it out.

But after Clive Pietzka's 999 call, an advanced paramedic practitioner carried out tests and discharged him.

The Welsh Ambulance Service Trust (WAST) job is one of those in a growing team who work to keep people out of hospital.

Solutions like this are being sought following ambulance queues for hospital and worst ever performance figures.

Mr Pietzka, from Barry, who has a heart problem, said initially he did not want to call an ambulance because of high demand.

"They're very busy with Covid and everything else. But the GP practice said to call 999," he said.

However, on this occasion a rapid response vehicle - a car with a single paramedic - came within 15-20 minutes and tests were performed, without a hospital trip.

"I'm over the moon," Mr Pietzka said.

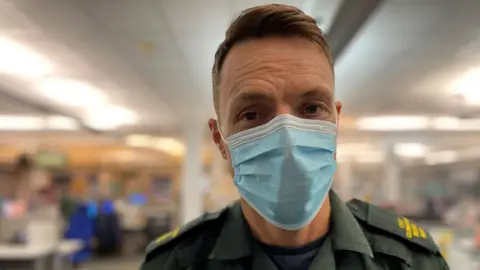

Advanced paramedic practitioner John McAllister who attended said he sees people more medical low acuity cases rather than emergency and trauma conditions.

Having served as a paramedic since 2009, he more recently studied for a masters qualification, paid for by his employer, with three days a week in university and two days with a GP practice.

"I use assessment techniques and diagnostic tools to assess patients, formulate a diagnosis then put a plan in place," he said.

"It's about trying to treat them at the right time and the right place, without having to take them to A&E."

Mr McAllister explained that Mr Pietzka's case was quite common.

"We worry about anyone with chest pains.

"But this job is ideal for me and is where advanced practice comes into its own, because as a paramedic I would have been quite reluctant to have discharged Clive."

But he explained a thorough assessment and appropriate tests reassured them both.

"He's happy he's home and it's another ambulance saved and another bed not being taken up in an emergency department."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast month's official figures showed the worst ever performance - again - for emergency departments and the ambulance service in Wales.

November's figures showed the ambulance service responded to just half of immediately life-threatening calls within eight minutes.

Adding to the pressure of the pandemic and winter demand, a shortage of social care workers to support patients' safe discharge means a large number of patients find themselves in hospital longer than medically necessary.

The knock-on impact means it is becoming harder for new patients to be treated and admitted.

Penny Durrant, the service manager for the clinical support desk at WAST regional headquarters in Cwmbran, said current challenges had led to growth in her team.

She said it was a "recognition of needing to do something different".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHer team is based in the control room, where calls come in and is made up of clinicians, paramedics, nurses and midwives.

They contact people often waiting a number of hours for an ambulance to see if there's a quicker, safe alternative.

In many cases, a trip to A&E simply isn't right for them.

"There's a lot of callers that just need guidance, rather than assistance," Ms Durrant said.

"It's a really challenging situation, but we need to make sure that the resources we have are used for the sickest patients."

Matthew Watkins, who was one of the paramedics working on the clinical support desk, explained how his call to a pregnant woman with Covid led to a different transport decision.

She'd phoned 999 as she was experiencing breathing difficulties.

On this occasion, Mr Watkins said she would need a trip to hospital, but he explained to her and her partner they may prefer to make their own way in.

"She's only a 10 minute car ride to the hospital, but it would be three to six hours for an ambulance," he said.

"Fortunately the family were able to assist. People need to be aware, if you've got access to your own transport, we'd much rather you be seen in a hospital environment than sat at home waiting for an ambulance."

Meanwhile, Nathan Maloney, a nurse on the clinical support desk alongside occasional shifts in A&E, said about 30% of the calls he dealt with resulted in people not needing hospital.

"We try and direct people to the most appropriate care, whether that's back to the GP, a district nurse, or acute mental health services," he said.

But he acknowledged that frustrations with overwhelmed services elsewhere caused people to call 999.

"People will tell us they're calling because they can't get through to their GP, which is not a clinical reason to phone 999. But GPs are seeing people and are working very hard.

"There's a lot of anxiety and people who have tested positive phone us for advice. It's important to get advice, but 999 is for life threatening services only."

It's an area the service is heavily investing in and while it isn't a face-to-face role, managers hope elements will appeal to those paramedics often waiting hours outside A&E.

"You can be doing one or two calls a day whilst you're out on the road," said Ms Durrant. "Whereas the clinical support desk clinicians may be able to do four calls an hour."

- HAYLEY PEARCE PODCAST : Tackling the issues that make your group chats go off

- WHAT'S THE BIG IDEA?: Food for the mind, and inspiration for the soul