Who has taken control of Scotland's councils?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe final deals are being put in place to decide who will run Scotland's councils, three weeks on from the local elections. How has the horse-trading played out, and who are the biggest winners and losers?

It has been three weeks since voters across Scotland trooped into polling stations to choose their councillors, but some are still waiting to find out who will be in charge of their local services.

The period since the ballots were tallied has been dominated by furious horse-trading between parties as different factions attempt to piece together an administration.

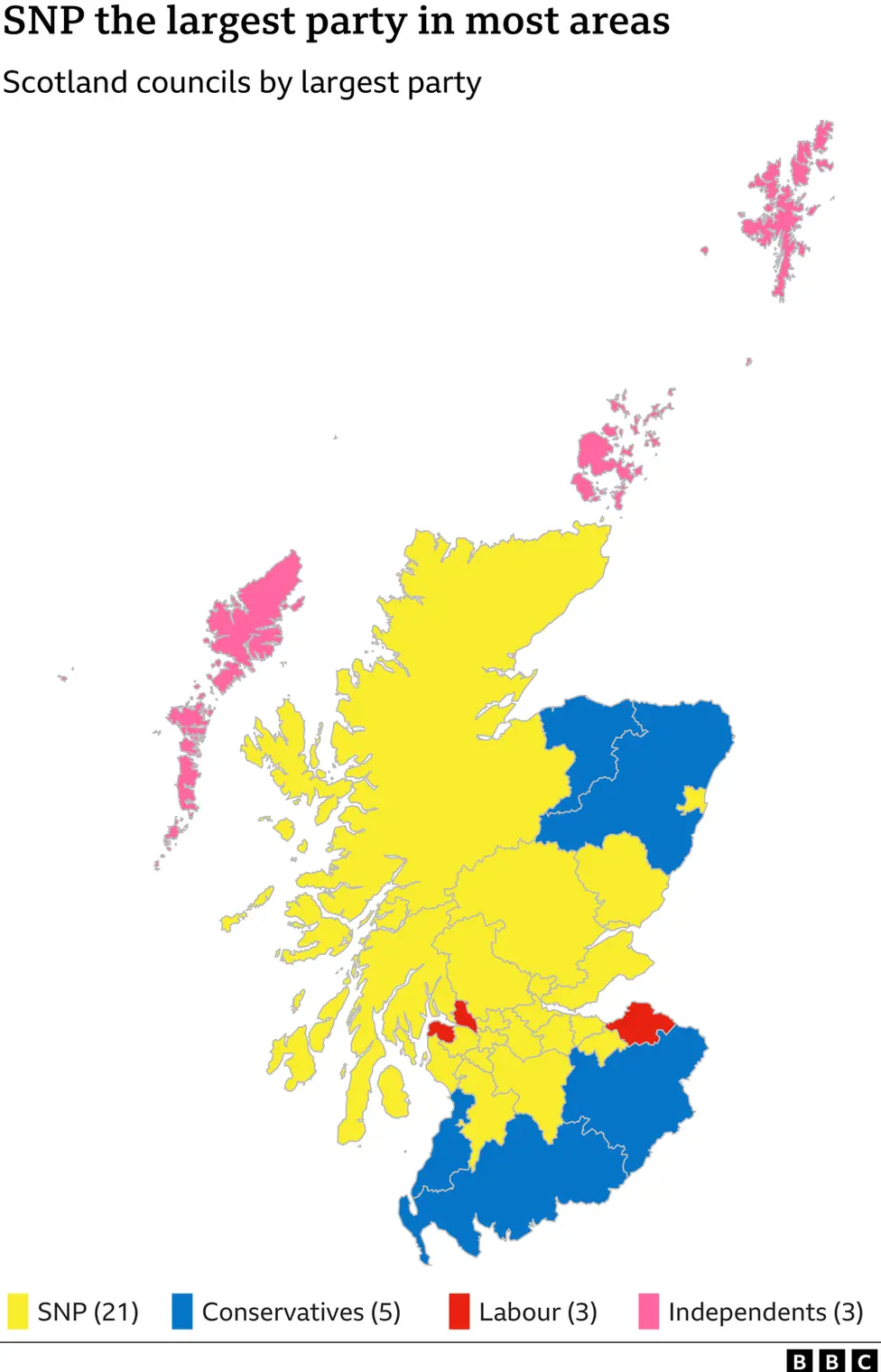

This is because the election produced only two overall majorities on the mainland - putting aside for now the island councils, dominated by independent members.

If parties want to wield influence at a local level, they need to work together.

But this year, the election campaign was characterised by pledges not to go into coalitions, and the following weeks have been littered with accusations of "backroom deals" and "stitch-ups".

Edinburgh was the last council to announce its new administration, and the capital is a good example of how talks have played out in other parts of Scotland.

It was previously run by the SNP and Labour, but the parties are at odds now. The SNP had teamed up with the Greens, and the pair have 29 councillors between them.

But the council ended up being run by 13 Labour councillors, because they have the backing of the 12 Lib Dems - leaving the nine Conservatives, rarely friends of the SNP, with a casting vote.

This is not a new thing. It is not necessarily always the case that the outright largest party ends up running the council - if other parties won't work with them, they cannot govern.

It can produce odd-looking results, like the 20 Labour councillors running Fife while 34 from the SNP sit in opposition. But ultimately the Tory and Lib Dem councillors there decided they would rather work with Labour - and being stuck short of a majority, there is little the SNP can do about it, other than complain vocally.

But for all of the sound and fury, there have actually been fewer deals shutting out the largest party this time round. Even if Labour take charge in Edinburgh, there will be eight such arrangements around Scotland - while there were nine in 2017.

And most of the parties have tried to make these deals where they can. For example, the Tories are the largest party in Dumfries and Galloway, but the council is to be run by a "rainbow" coalition including the SNP, Labour, Lib Dems and independent councillors.

A Labour-Lib Dem-independent group has squeezed out the SNP in South Lanarkshire, while Conservative-Lib Dem-independent coalitions have pipped them in Argyll and Bute.

Not all deals are this controversial, of course. Most councils are still to be run by the party which won the most votes, and there are plenty of examples of other parties abstaining in votes to leave them as a minority administration.

There are also places where the largest party has teamed up with another group in order to command an overall majority. The Lib Dems are actually in coalition with the SNP in Aberdeen and with the Tories in neighbouring Aberdeenshire.

So how has the rhetoric which has flown around pre- and post-election translated into deals?

Anas Sarwar said he didn't want Labour to enter into coalitions with the SNP or Conservatives. If we define a coalition as a formal arrangement which actually brings another party into the administration running the council, this has only happened in Dumfries and Galloway.

This has chiefly hurt Labour, with the party looking set to be on the administration of, at most, 10 councils - down from 15 in 2017, when the party did five deals with the SNP and one with the Tories.

Labour has profited in some areas where the SNP is the largest party, but other groups do not want to work with them - leaving the second-placed party as the only viable option.

The SNP has been understandably vocal about this, but overall has not actually lost ground - the party looks set to be on the administration of 15 councils, up one from the 2017 polls.

The Conservatives have lost control of a couple of councils and gained a couple of others, dropping from seven to five overall, while the Lib Dems are junior partners on five.

The Greens are backing the SNP in Glasgow, but are not part of the administration - and are on tenterhooks to see if they can get in the door in Edinburgh.

Reuters

ReutersThe way parties have approached and responded to the current round of deal-making has been driven not just by local priorities, but also larger national strategies.

Labour's initial pledge not to form coalitions with the SNP or Tories reflected the fact the party has bled voters to both in recent elections, and badly wants to win them back.

Mr Sarwar needs people to believe that voting Labour gets you Labour - not another party through the back door. This means the party has ended up with less influence at a local level, but the leadership's calculation is that it will be worth it in future Scotland-wide contests.

Meanwhile, both the SNP and Conservatives clearly have an interest in keeping voters away from Labour, in order to maintain their positions in first and second place in Scottish politics.

They have both prospered from facing off in a two-horse race in recent years, and would like to nip any idea of a Labour revival in the bud. But, of course, this has to be balanced with persuading Labour to do deals where possible in order to shut their other rivals out.

Voters may look on at this complicated political dance in bemusement - but at least, in the coming days, they should know exactly who it is they can complain to about their bins.