The numbers behind Scotland's council election results

PA Media

PA MediaScotland's local election results saw the SNP winning big once again and the Conservatives falling back.

Results varied across the country's 32 local authorities, but what can the national trends tell us about how the country's politics could be changing?

Friday was a good day for all of the main parties, but for one glaring exception. With the Conservatives taking an electoral kicking, the question was which of the others could profit most from their losses?

The SNP were dominant once again, winning 34.1% of the votes cast north of the border. This was up 1.8 percentage points on the last council contest in 2017, and the 11th Scotland-wide election in a row where the party has come out on top.

Labour were second with 21.7%, up 1.6 points - overtaking the Tories, who dropped 5.8 points to 19.6%.

The Lib Dems won 8.6% of the vote, also up 1.7 points, while the Greens had an even bigger jump in share, up 1.8 points to 6.0%.

The Tories were joined in the doldrums by Alex Salmond's Alba Party, which took just 0.7% of first-preference votes. They stood far fewer candidates than the established parties, but were really not close to making an impact in any part of the country.

Incidentally you may see a few different vote share changes bandied around. It's difficult to calculate precisely because there have been some boundary changes since 2017 - the figures here are based on the 326 unchanged wards in an effort to provide a like-for-like picture.

Of course in an election run using the single transferable vote system, first-preference ballots are not everything.

In fact there was one ward in Edinburgh where a Lib Dem candidate was the first choice of just 1.4% of voters, but was ultimately elected via transfers.

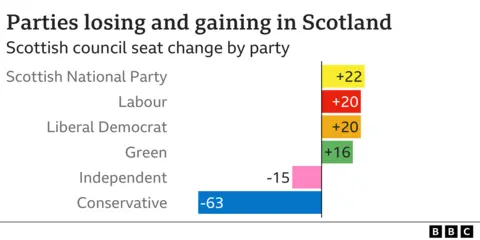

So the true measure of success might be seats - and again the SNP were clear winners, with 453 councillors elected.

This was the biggest increase of any party, up 22 on 2017's totals, and another example of the party defying political gravity after 15 years in government at Holyrood.

Labour gained 20 seats to be second on that measure too, on 282, while the Tories lost 63 seats to land on 214.

These figures are somewhat skewed by the earthquake last time out, when Labour lost 133 councillors and the Conservatives more than doubled their total to 276.

It will be little comfort for the Tories, who lost one seat in North Lanarkshire to the British Unionist Party and were outpolled by the Rubbish Party in Irvine Valley. But exclude 2017, and this was actually their next-best result in terms of seats since 1980 - and Labour's worst since 1977.

It is difficult to make direct comparisons to the era of district and regional authorities, but Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar technically tied the district council poll record of Jim Callaghan - which was at the time seen as a disaster.

Returning to second place is a big symbolic win and this may yet be the beginning of a Labour revival. But they have an awfully long way to go back to their peak - Tony Blair had more than 600 councillors around Scotland in 1995, albeit under a first-past-the-post electoral system.

The Lib Dems are also hoping for a return from the wilderness under new leadership, and gained the same number of seats as Labour to finish on 87.

That said, the party has not yet recovered fully from the coalition with the Tories at Westminster - Alex Cole-Hamilton's 20 gains this time only begin to offset the 98 seats shed across the 2012 and 2017 elections.

The Green totals are lower overall, with 35 seats, but 16 of them are new - and many are in untapped areas of the country, with the party winning representation in places like North and South Lanarkshire for the first time.

Having made particular gains in Glasgow and Edinburgh, the Greens will be hopeful of replicating their Holyrood arrangement with the SNP and entering government at a local level.

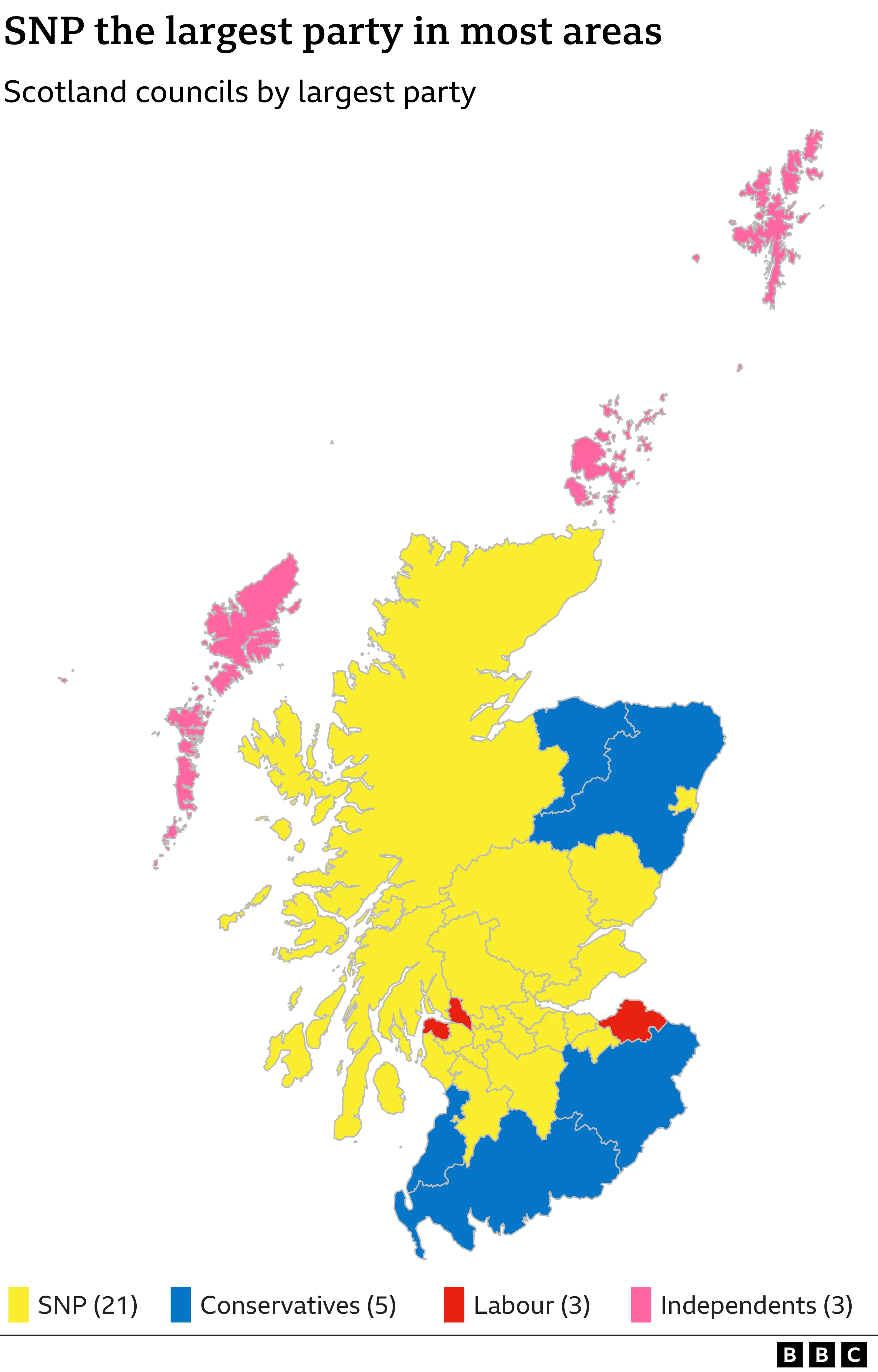

Talking of forming governments... who will end up running the 32 councils?

That question has only really been answered in two places. The SNP will have majority control of Dundee, while Labour has achieved a similar feat in West Dunbartonshire.

Talks will begin in earnest about who can form an administration elsewhere, but the numbers provide a decent guide as to who the winners might be.

The SNP is now the largest party on 21 councils, up five on 2017, and will likely have first dibs on running many of them.

The Conservatives are biggest in five council areas to Labour's three, while the remainder are dominated by independents.

This does not, however, necessarily translate automatically into who runs the show.

In 2017, there were nine out of 32 council areas where the largest party ultimately ended up in opposition, with other parties either banding together in coalition or propping up one group as a minority administration.

Labour in particular profited from this, running a number of councils where they were outnumbered by the SNP - which may raise questions about Anas Sarwar's approach of barring his councillors from entering formal coalitions.

PA Media

PA MediaIndependent councillors are always a significant factor in local elections - they won just under one in 10 first preference votes in this election, and they will continue to run the councils in Orkney and Shetland and the Comhairle nan Eilean Siar.

The number of independents does seem to be on the wane, however - the field of non-affiliated candidates this year was almost half of the total who stood 2012.

In the end, the number actually elected only fell by 15, to 152 in total. That number includes three councillors returned by minor parties alongside the "true" independents.

As small as this drop ultimately was, it still had a big impact in some areas.

In Moray, the Conservatives became the largest party by gaining three places on a council where six independent seats were surrendered.

And the SNP ended up the largest group on Highland Council for the first time, despite not making any gains - they stood still on 22, but there were seven fewer independents returned, dropping their total number to 21.

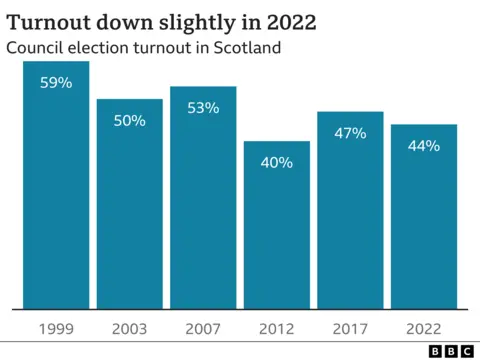

Finally, turnout was 44%, down almost three points on 2017.

There had been hopes that participation might rise off the back of increased registration for postal ballots and a record rate for last year's Holyrood contest, but this ultimately failed to materialise.

Douglas Ross has tried to wave away Tory losses as evidence that his voters stayed home rather than backing another party - it's worth repeating that his troops shed almost six percentage points of vote share, so a decent number of 2017 Tory voters likely did in fact go elsewhere.

But he may have a broader point - public dissatisfaction with politics and politicians generally may have translated into lower participation.

There was even apathy from candidates in some areas, with eight wards where there wasn't even a vote because not enough people came forward.

And in a few wards there were actually fewer candidates than seats, meaning there are already three vacancies - so some unlucky returning officers are already planning by-elections before the dust has even settled.

Data journalism by Wesley Stephenson and Christine Jeavans