Will rows over pay lead to more industrial action in Scotland?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLocal authorities are facing the prospect of strikes unless there is an improved pay offer for workers. The Scottish government says it is working with council body Cosla to explore options for solutions. Recent months have seen several other disputes over pay and conditions. So, is Scotland facing a summer of discontent?

Train drivers and signallers, BT telecom and Royal Mail employees, airport workers and cabin crew, supermarket workers, bus drivers and university lecturers, even lawyers in criminal courts - the striker has become a symbol of 2022.

Many more could be set to follow in their path, including a wide range of local government workers. One of their main unions, Unison, is planning to disrupt schools, early years centres, nurseries and waste and recycling centres across Scotland.

Scottish teachers lodged a 10% pay claim, before realising that price inflation could rise even higher. There is union talk of a strike ballot when the summer holiday is over.

Firefighters say a 2% pay offer is "insulting" and are also talking up strike action, while Scottish nurses close their strike ballot this Thursday.

Scottish police officers will have more to say the following day about stepping up their "withdrawal of goodwill", while they lack the legal right to strike.

Another symbol of this year was the video call sacking of P&O ferry crews, with their replacements hired on much weaker contracts.

It was a powerful image of the way some employers treat staff, and reinforced public support for trade unions at the very moment that price inflation was about to take off, leaving most pay increases struggling far behind.

Why are there so many strikes?

PA Media

PA MediaThe simple answer is pay. Price inflation is racing ahead of pay rises at a rate that few foresaw even in early spring, when many pay deals should have been settled. Workers want to hold on to the spending power of their pay.

Government-funded employers have limited flexibility to meet expectations that pay will catch up with inflation. Private sector employers are being hit by rising costs - notably for energy, but they also suffer from disrupted supply chains and shortages of skilled staff.

That should give workers a lot of leverage to demand higher wages, and that's what they've been getting in some privately-run sectors, such as haulage. In construction and finance, it's been a bumper year for bonuses.

With that backdrop of a tight labour market, trade unions could expect to be in a strong position. They represent slightly more than half of public sector workers. Years of squeezed budgets have seen their earnings eroded, relative to prices and to the private sector.

Trade unions represent only around one in six private sector workers, but they are not evenly spread. They are strongest in former nationalised industries and companies, including transport and utilities, but much weaker in sectors with less formal employment structures - often where young people are on lower pay, such as hospitality.

So where they have leverage over employers, trade unions are making it clear that they are willing to deploy it over pay, if necessary through strike action.

Why is this being called the summer of discontent?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe term suggests a parallel with the Winter of Discontent in 1978/79. There were thousands of strikes, and around 30 million working days were lost to industrial action.

It is etched into folk memory, not least in the minds of newspaper editors.

Inflation was running high, although lower than it runs today.

Unions represented twice the proportion of workers that they do now. They were frustrated at the pay restraint required of them by the Labour government led by Jim Callaghan. Higher wages had been leading to an upward cycle of higher prices.

One consequence of that chaotic winter was Labour's heavy defeat to Margaret Thatcher in 1979. She was elected with a mandate to tear into both price inflation and the trade unions' ability to strike.

As that was nearly 44 years ago, you have to be a Baby Boomer to remember it. Other generations have come along who don't share - according to recent opinion polling - as negative a view of trade unions.

Those generations may be less likely to know that "winter of our discontent" is Shakespearean - the opening line from Richard III. It was, incidentally, to welcome the end of that winter.

But it looks as likely that this year will see a more active autumn of discontent, or a deepening of it in winter, as inflation peaks.

Some energy analysts are looking to the winter after next, forecasting continuing difficulties. This may come to seem, by comparison, what Shakespeare's Richard called "glorious summer"… before things turned nasty.

How political are the strikes?

There is politics attached, for sure. As the rail industry moves out of the private sector, rail unions are using leverage with governments at Westminster and Holyrood.

It's easier to focus a campaign on a cabinet minister than a faceless chief executive, whose accountability was to shareholders overseas.

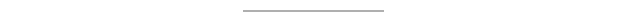

Also, summoning up the demons of 1978 is a way of mobilising Conservative Party members as they vote for their new leader and prime minister.

Facing a series of one-day rail strikes, there has already been a rapidly-enacted change in the law to make it easier to introduce agency workers where union members are striking.

We have had warnings about the impact of price and wage increases spiralling, again seeing reference to that problem in the 1970s.

The signs from the Tory leadership candidates are of further measures to constrain trade union power - once more evoking the spirit of Margaret Thatcher.

For Conservatives, such strikes also provide an opportunity to put political heat under the Labour Party.

Strike action means union affiliates of Labour expecting political support, while moderates at Westminster prioritise their mission to look as credible as possible for swing voters at the next election.

What are the differences in Scotland?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe recent 5% pay rises recommended by independent pay review bodies affect much of the public sector in England. In Scotland, these cover little more than doctors, dentists, civil servants, judges and the military.

However, the review body recommendations influence negotiations in Scotland, at least as a benchmark below which neither Scottish unions nor the Scottish government want to fall.

With budgets already tightly stretched to meet commitments for public services and welfare payments, while without further borrowing powers and no appetite for further income tax increases, Scottish ministers see themselves as constrained by spending decisions made at Westminster.

So without the funds to match price inflation for Scottish teachers, health service workers, police, firefighters, local government workers and so on, the Scottish government is turning to Westminster - either for help or to blame, depending how you perceive it.

Local government unions say that the offer given to English counterparts is far ahead of anything offered so far in Scotland, at least for the lowest-paid workers.

What about non-pay elements of these disputes?

PA Media

PA MediaEmployers have wish lists of changes they would like to see, to improve efficiency and reduce labour costs. Staff do too, more often to improve conditions such as holiday entitlement or pension provision - or unions want to defend existing agreements at risk of erosion.

In the case of rail workers, there is a battle being fought over job losses. Employers want to reduce payroll costs and headcount in areas such as train guards or staffed ticket offices.

The RMT transport union has a better track record than others at getting its way in such disputes. Partly, that is because it is focussed on a few sectors, while large amalgamated unions such as Unite, GMB or Unison have less focus and depend more on decentralised negotiating, sometimes through inexperienced, under-resourced local officials.

An important element of strike action or other disruption to public services is securing public support. The risk unions take is of alienating the public with the inconvenience of cancelled trains, or bins going uncollected.

YouGov has published opinion survey data suggesting there is support for the right to strike. Trade unions were seen as playing a positive role in Britain by 32% of those questioned, and a negative role by 26%.

Ipsos Mori also has findings on attitudes to unions, which point to sympathies running ahead of strike support.

Across the UK, for instance, it finds 71% would sympathise with a nurse's pay campaign, while 60% would support a strike. For school teachers, 51% would sympathise, and 42% would support a strike. The least sympathy is for barristers, civil servants and academics.

Has the pandemic made a difference?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUnions were widely seen as playing a positive role at the start of the pandemic, cooperating with bosses to apply infection control measures and to support workers who were required to stay at home.

Coming out of the pandemic, the changing shape of commuting is one example where unions face a new challenge.

With only around three-quarters of the ticket revenue train operators used to have, much of that because of many people continue to work from home, rail services have to be adapted to the routes and journey times people now want.

The pandemic also brought support for health and social care workers, including weekly doorstep applause and fund-raising. Train drivers and council workers are also reminding us that they continued to provide vital public services.

Such workers hope to turn that into public support for pay campaigns. They have to do so without alienating that support by harming public services.