Angel of the North: The icon that was nearly never built

Andrew Yates/AFP/Getty Images

Andrew Yates/AFP/Getty ImagesThe Angel of the North's iconic status is taken for granted. Yet it was so nearly never made. Strong local opposition, engineering difficulties and even the doubts of its own creator, Sir Antony Gormley, threatened to scupper it several times.

When the Angel arrived in Gateshead in the middle of an unseasonably mild February night 20 years ago, it was treated like royalty.

The convoy of body and wings eased past waving crowds, illuminated by police escort headlights and streetlamps, followed by a traffic tailback cortege.

"Everybody had been told to stay away - but they didn't," says Gormley.

"By midday we had 2,000 people there."

Gary Porter, who drove the 48-wheel trailer carrying the Angel's body, remembers people on "every corner, every roundabout, every turn - hundreds, thousands, everywhere".

He had already driven the 28-mile route from Hartlepool over and over, checking the sculpture would fit under bridges and around corners.

Inconvenient road signs and lampposts had been removed.

"That was not the day to get a corner wrong and hit something," he says.

The Angel's night-time arrival was "spectacular", says Sid Henderson, then chairman of Gateshead Council's libraries and arts committee.

"It wouldn't have been nearly as exciting [during the day] would it?" he says.

But, at any point during the previous eight years, the Angel could have been halted for good.

'It has to be five double-decker buses high'

Sally Ann Norman

Sally Ann NormanGormley had initially been, by his own admission, "quite snooty" about the project.

When Gateshead Council first invited him to submit his ideas he refused, telling council officers he did not make "motorway art".

While today he is globally famous, in 1990 his emerging renown was contained within the art world.

It was a picture the council sent him of the mound - next to the road and covering 300 years of mineworkings - that piqued his interest and persuaded him to visit.

Gautier Deblonde

Gautier DeblondeAnna Pepperall, the visual arts manager in Gateshead Council's arts team, remembers "talking and talking, trying to persuade him that it was worthy of a site visit".

She believes he may have had reservations about the "huge risk" of the project, given the failure of his proposed Brick Man sculpture in Leeds, which was defeated by red tape and the same kind of opposition which later threatened the Angel.

But, once in Gateshead, he was "very excited", she says.

The prominent location - on the landscaped site of the old Teams Colliery miners' baths - appealed.

"I think the combination of the site and the view and the history was very attractive," she says.

"If you're going for a landmark sculpture you want it to be seen."

Antony Gormley

Antony GormleyGormley himself remembers walking up the hill with Gateshead councillors.

One, Pat Conaty, said to him "what we need Mr Gormley is one of your angels", he says.

"I didn't even know that they knew that I'd made a work called A Case for An Angel," Gormley says.

"And I said, well, if you're serious about this, it has to be about five double-decker buses high."

He laughs at the memory of their stunned silence.

'It could have changed everything'

Of course, the Angel of the North might never had been built were it not for a senior councillor beginning a job as a trainee store manager at Marks & Spencer.

In 1994, the council's Art in Public Places panel was considering a shortlist of two: Antony Gormley and the significantly more well-known, and already knighted, Sir Anthony Caro, who would later co-design London's Millennium Bridge.

But, on the day of the meeting to recommended one for approval, only three of the panel's six members turned up to vote.

One opted for Gormley and one for Caro. Sid Henderson, the panel's chairman, cast the deciding vote.

Missing was Liberal Democrat opposition councillor, Jonathan Wallace, prevented from attending by his new job.

Becoming increasingly well known as a critic of the project, he might have swung the vote.

"It could have changed the debate and argument that we had afterward," he says.

Ben Stansall/Getty Images

Ben Stansall/Getty ImagesMs Pepperall had added Gormley to a long list of about 40 internationally significant artists drawn up by the council's arts team.

He was "at the forefront of a young generation of sculptors" while Caro was a "huge national figure", Ms Pepperall says.

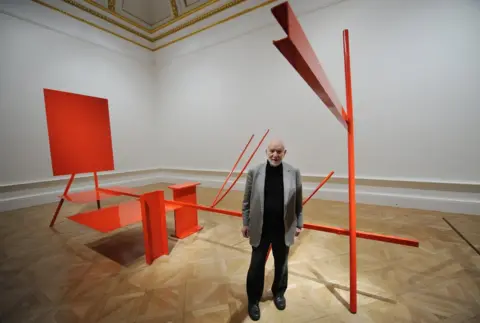

Gormley's work largely showed the human form unusually positioned or located while Caro's pieces were abstract constructions of intertwined metal of differing thickness and shapes, often brightly coloured.

Caro sketched a design for councillors based on the Newcastle to Gateshead bridges, Mr Henderson says.

"It was very impressive and hard to say whether or not that would have been as popular, or less popular, than the Angel," he says.

Ms Pepperall believes a more abstract Caro sculpture could have worked.

It would have attracted a different sort of public and may not have provoked the same initial negativity, she thinks.

But the Angel "somehow fitted the bill".

'Nazi....but nice?'

Antony Gormley

Antony GormleyWhen the Gormley design was revealed as the preferred option, it was met with a torrent of negative publicity.

The list of objections was long and varied: the Angel would cause accidents on the nearby A1, interfere with television reception, spoil views, attract lightning strikes and tempt vandals.

Some thought it was blasphemous or a waste of money. Others simply disliked the design.

As one of the Labour council's chief Angel advocates, Mr Henderson found himself regularly challenged in pubs.

The council's Liberal Democrat opposition started a campaign to stop the sculpture and raised a petition.

Owen Humphreys/PA

Owen Humphreys/PAMany refused to believe the £800,000 it would cost to build - money ring-fenced for the arts - could not be spent on the schools or hospitals they thought more worthy.

"You couldn't convince people," Mr Henderson says.

"The thing is, if we didn't get that money then it would just go somewhere else for the arts and not for Gateshead."

Meanwhile, headlines in the local papers shouted about wasted money and ugly art.

The now defunct Gateshead Post even ran a story comparing the Angel to a 1930s German sculpture, with the headline: "Nazi... but nice?"

Roger Woocdock/Gateshead Post

Roger Woocdock/Gateshead Post

The paper unfavourably highlighted similarities in the two pictures - of Albert Speer's Icarus and Gormley's earlier work, A Case for An Angel III.

The Newcastle Evening Chronicle ran dozens of critical articles.

Its former editor, Alison Hastings, says her paper did not wage a concerted campaign against the Angel but was, perhaps, "not very supportive" of it.

"It's one of those things that you look back in hindsight and think, well, you know, we got that wrong, we got that wrong to be as negative," she says.

"But I wouldn't say that it shouldn't have been scrutinised."

The media were basing coverage on the public mood, she stresses.

"If everybody had been really, really keen on this idea, and we were out there saying it was a terrible idea, we would have lost credibility with the readers."

But the media "campaign" was frightening away sponsors and could have destroyed the Angel, Ms Pepperall believes.

You might also like:

Why would a national company spend money on a local project if the only result was bad publicity for its brand?

"The Henry Moore Foundation wouldn't support it because they felt that it had had too much negative input at the beginning," she says.

Gormley, not wanting to force his work on a local population who did not want it, was also prepared to "call it a day".

The Nazi-referencing headline, in particular, had unsettled and upset him.

Two of the council team travelled to meet him and offer reassurance and encouragement, persuading him not to give up.

As Gormley described it in 2008, they "basically put me back on my horse and gave it a big slap".

'Will this thing stand up?'

Francesca Williams

Francesca WilliamsDoubts about whether the Angel was desirable and affordable were joined by doubts about whether it was even possible.

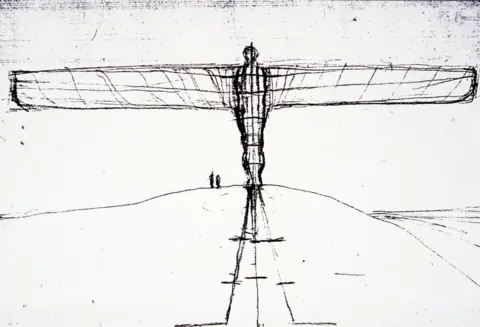

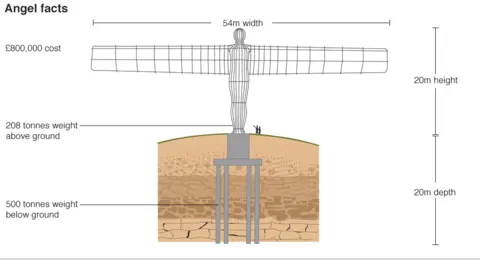

Neil Carstairs led the team of Ove Arup engineers tasked with taking the Angel from concept to "something which could actually be built 20m high".

Based on a cast of Gormley's body, the top-heavy 200-tonne sculpture resting on narrow ankles was in danger of falling over.

"The issue is that, if you or I were standing on top of a hill in a howling gale, we wouldn't be standing with our feet close together, vertically upright with our arms stuck out," Mr Carstairs says.

Using computers to make virtual 3D models, they scaled up Gormley's dimensions to see what would work. Gormley was closely involved, keen to find ways of achieving something as close to his concept as possible.

"He didn't just produce a sketch on the back of an envelope and say to somebody go away and build it," Mr Carstairs says.

Keith Paisley/Antony Gormley

Keith Paisley/Antony GormleyGormley and Carstairs scoured the region but it seemed no company could make the Angel within the £800,000 budget.

"There was definitely concern that it might not be feasible," Mr Carstairs says.

In the end it was Hartlepool Steel Fabrications who came up with a solution that would keep the Angel upright and within cost.

Steel thick enough to take the Angel's weight and withstand the wind could not easily be bent into the shape of Gormley's body.

The solution was to build a structural central core, cover it with a thinner outer "skin" and add strengthening ribs made from the same thick plate as the core.

By comparison, filling the mound with "substantial" foundations, twice as heavy below ground than the Angel was above it, was child's play, Mr Carstairs says.

Gateshead Council/BBC

Gateshead Council/BBCPlanning permission was another hurdle to overcome. Lightning strikes and disrupted television reception aside, the potential for traffic accidents was a real hazard that had to be addressed.

The Highways Agency was worried the sculpture would distract motorists on the busy A1.

It had to be positioned facing oncoming traffic so drivers would see its full wing span in advance, while still looking where they were going. Facing Gateshead, as might have been expected, the Angel's front view might take drivers by surprise, tempting a potentially lethal sideways stare.

But road safety opinions change and, in January this year, Highways England issued a report on good road design which suggested "statement structures" like the Angel of the North actually help reduce accidents by keeping drivers alert to their surroundings.

Sally Ann Norman

Sally Ann NormanGormley remembers the moment of truth, when the Angel's component parts were brought together.

"It should have been filthy weather, it should have been quite cold but, in fact, it was a really balmy night," he says.

"I can remember... all of the kids - Paloma and Guy and Ivo - climbing inside.

"Where the wings attached to the body it was still open so you could get in.

"All the kids were in there and making these booming sounds inside the body.

"It was difficult to get them out actually."

Seeing the Angel with only one wing and hoping it wouldn't "keel over" scared Gormley.

"Will this thing stand up, will this thing support its own weight, will this wing fall off?"

As it happened, the wings were only just attached before the mild weather was replaced by gales.

'Overnight it became iconic'

Andrew Yates/AFP/Getty Images

Andrew Yates/AFP/Getty ImagesWhen the Angel was officially unveiled, there were still some who disliked it.

London Evening Standard art critic Brian Sewell did not even bother to visit the sculpture in person, but still hated it.

"I've seen almost everything else that Antony Gormley has done and that was absolutely no inducement to travel 300 miles to Gateshead to see the largest and I think probably the emptiest, the most inflated, the most vulgar of his works," he said at the time.

But his was increasingly a lone voice. The mood had started to change when Gormley's Field for the British Isles was exhibited in the former Greenesfield British Rail works in Gateshead during the 1995 Year of Visual Arts. People visited - and they liked it.

Then, officially unveiling the Angel, Lord Gowrie, chairman of the Arts Council, called it a "piece of public art unique in the history of this country".

It would, in time, be compared to the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty, he said.

Sally Ann Norman

Sally Ann NormanHyperbole, maybe, but first sight of this imposing structure on the hill undid many of the Angel's critics.

Even committed opponent Jonathan Wallace faced a dilemma.

"I was driven up there by my partner on the Monday morning to do all the media interviews," he says.

"As we drove up the A1 from the Coal House roundabout on the Team Valley, I saw it sort of emerging.

"It was a huge monumental piece of art and I did think, actually, it does feel quite impressive, even though I was there to do interviews about why we hadn't supported it."

A few months later, a group of Newcastle United fans decided the Angel was missing something.

At dawn, using catapults, rubber balls and fishing line, they hauled a massive, custom-made Alan Shearer number nine shirt over the 65ft statue.

The police were unimpressed but Gormley credited the stunt with effecting a "huge shift... a real cultural shift" in favour of his sculpture.

"It was almost like, if you liked art you, were a sissy and real boys played football and knew everything about football but, from that point onwards, in the locker rooms of the North East, it was all right to talk about art," he later said.

Mr Wallace believes people also just "got used to it".

"It became part of the landscape and, no matter how ugly or grotesque you think it is, people seem to have developed a sense of ownership about it," he says.

Photographer Sally Ann Norman had been commissioned by Gateshead Council to record the Angel's construction.

"I do remember feeling everyone's taking this on, everyone's loving it, everyone's taken ownership," she says.

"I felt really proud - of not just Gateshead, the North East."

Before the Angel the symbol of Tyneside was the Tyne Bridge.

"The minute the angel went up it just took it over," Ms Norman says.

"Overnight it became iconic."

Sally Ann Norman

Sally Ann Norman