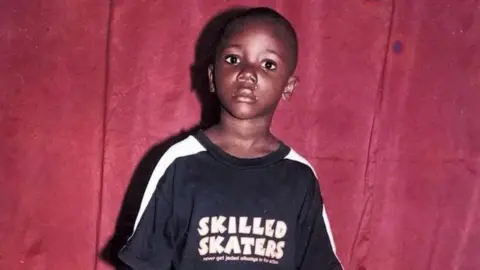

County lines: 'I was nine when drug dealers recruited me'

BBC

BBCA former gang member was forced to traffic guns and drugs for more than 10 years before he was identified as a victim of child criminal exploitation.

Sosa Henkoma was nine years old when he was recruited to deliver packages for the violent gang.

Trapped in a life of crime for the next decade, he ran guns and drugs between London and Liverpool.

He said he counts himself lucky to still be alive after he was stabbed at least 11 times and shot at twice.

It was only after Sosa was convicted and jailed that authorities deemed him to be a victim.

"I saw people die on the streets, I nearly died myself," he said.

"Even if I tried to escape the life, I couldn't. As far as I was concerned, it was where I was going to die. And it was like I was dead inside."

Sosa told his story as part of a BBC North West investigation which found:

- On average, more than 40 children a day are being referred to social services in England amid fears they have been exploited by gangs

- Department for Education data shows the number of children in England referred to social services as potential victims increased by 42% in the year ending April 2023

- The north-west of England had 2,100 cases - the most outside London

- Fewer than one in 10 of those potential victims were supported or protected by the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) - a government framework designed to help at-risk children

- A report shared exclusively with the BBC warned exploited children were falling through the cracks because of understaffed, overworked and poorly trained councils and police

The Local Government Association admitted providing support for children was becoming "increasingly challenging" for cash-strapped councils, while the Children's Commissioner for England said the BBC's findings were "only the tip of the iceberg".

Sosa, who came to England from Nigeria aged eight, was living in care after suffering horrific abuse at home.

Soon afterwards, he was asked to drop off parcels for a drugs gang in South London.

"I didn't know what it was," Sosa said. "I used to see them in the park and just saw some people wanting to help me and I wanted to please them, so I did it.

"I had a bike and they just gave me the parcels to drop off and I picked up the cash. I was nine - I didn't ask questions, I just did the favour."

Sosa Henkoma

Sosa HenkomaSosa was then sent to Margate on the Kent coast to hand out more parcels, unaware he was being used as a drugs mule for a county lines operation - where city gangs extend their activities into small towns across the country.

"I was there for three days," he said. "Then on the third day, a gang of masked men burst through the door with shotguns and machetes and held a shotgun to my head. It was terrifying."

Scared for his life, Sosa said he went to social services and told them everything.

"They thought I was making it up," he said. "They said I was 'fantasising'."

Sosa felt he had no choice but to go back to the gang that had raided the house and they vowed to protect him from rivals.

"I had no-one at the time, only them," he explained. "So I stuck around. They looked after me, showed me stuff."

They taught him how to deal drugs around the housing block where they operated - and gave the then 12-year-old a revolver.

"They taught me how to fire it [and] said if I didn't shoot when they asked then they'd shoot me," he said.

Gang life

Sosa was put to work as a "mini enforcer", running drugs and guns from London to Liverpool.

"I was their little protégé, their child soldier," he said. "They loved having this kid who'd do anything for them, anything they said."

He spent years entrenched in gang life and still bears the brutal scars.

"I was stabbed at least 11 times," he said. "I was shot at but never hit. I had this street name: The Devil That Walks On Earth."

Sosa was eventually arrested at 14 and charged with possession of firearms and causing grievous bodily harm.

He said the birth of his daughters - one during another stretch in prison for firearms offences before his 18th birthday - brought him back from the brink.

"I just thought, 'I have to save myself'. And my daughters were the reason to do it," he said.

Sosa

SosaWhile in prison for the second time, Sosa was assessed by a psychiatrist and, after a series of tests, was found to have been groomed.

Under the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), he was flagged as a modern slavery victim in 2020 and put in a safe house in Manchester.

A report, shared exclusively with the BBC, highlighted inadequate police and council resources when it comes to identifying children at risk, making referrals into the NRM and supporting child victims.

It said there was a "lack of a comprehensive and overarching child exploitation strategy" and half of all authorities that made referrals from 2018-2023 could not provide basic information on the children referred.

The report was written by the Every Child Protected Against Trafficking (Ecpat) charity, working with the University of Nottingham.

Researchers used data from a six-month online survey and a series of Freedom of Information requests submitted to local authorities.

Ms De Souza said official figures did not scratch the surface and she had seen a real rise in child criminal exploitation since the pandemic.

"We are treating them as criminals instead of seeing [their] vulnerability," she said. "They are victims of criminal exploitation, yet many are still being seen as perpetrators.

"Local authorities are well trained in how to spot neglect and abuse in the home but can they spot it when it's happening outside? That's what we need to get to."

She said powers available to local authorities should be reviewed and more "joined-up thinking" was needed.

Councillor Louise Gittins, who chairs the Local Government Association's Children and Young People Board, said councils were committed to keeping children safe but funding pressures meant providing the "best possible support for all children is becoming increasingly challenging".

She added: "With record numbers needing support, councils - alongside charities and campaigners - are united on the urgent need for funding to ensure all children and their families get the support they need, as soon as they need it."

Sosa, who has undergone intensive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma, said he had turned his life around.

He is now studying for a degree in criminology and sociology and works with anti-trafficking charities, mentoring at-risk young people.

He also trains the NHS, police and social workers on how to work with victims and young people at risk from child criminal exploitation.

A Home Office spokesperson said: "Protecting children from abuse is a key priority and there is always more we can do.

"This government will stop at nothing to make sure every child, in every part of the country, grows up in an environment that is safe and secure."

They added up to £5m was being invested over three years to support county lines victims and their families.

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, X and Instagram? You can also send story ideas to [email protected]