British Empire Exhibition: The forgotten event that took the world to Wembley

Alamy

AlamyOn St George's Day one hundred years ago, King George V stepped on to the turf of the newly created Wembley Stadium to open the British Empire Exhibition - and in doing so became the first UK royal to make a live radio broadcast.

Running for two six-month long seasons, in 1924 and 1925, the event saw grand pavilions, life-sized butter sculptures, a coalmine, a recreation of Tutankhamen's tomb and elaborate theatrical performances featuring thousands of people and animals come to a corner of north-west London.

One guidebook heralded it as "by far the most important undertaking of the kind ever attempted in this or any other country".

It welcomed some 27 million visitors in the time it was open - but these days is barely remembered.

What was the point of the exhibition and what did it achieve?

Getty Images

Getty Images"I can just remember the excitement and the hope," remarked poet laureate John Betjeman, speaking 50 years after the King's historic address, for his seminal documentary Metroland.

Crammed into a 215-acre site which only years before was rural parkland - and the site of a failed attempt to build a rival Eiffel Tower - were 15 miles (24 km) of roadways named by Rudyard Kipling and dozens of buildings and pavilions representing the many different territories of the British Empire.

"The official guide talks about it as a kind of family party of Empire. This idea that you can have a kind of trip around the British Empire. That you're transporting yourself, you're going on a kind of journey," explains Deborah Sugg Ryan, broadcaster and professor of design history at the University of Portsmouth.

Getty Images

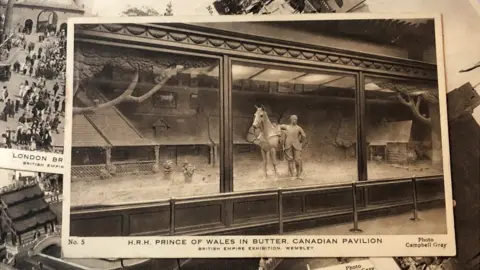

Getty ImagesIn the Canadian pavilion, a working model of the Niagara Falls stood near a life-sized butter sculpture of the Prince of Wales, with his horse, in a huge refrigerated unit. South Africa had an ostrich farm. Burma - now Myanmar - exhibited rice, oil and timber, and Ceylon - now Sri Lanka - had tea and rubber displays.

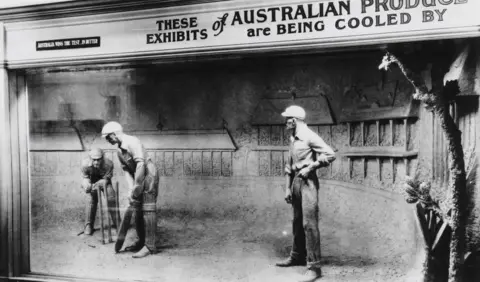

As for Australia, it displayed sheep-shearing and its own butter sculpture, of legendary England cricketer Jack Hobbs being bowled as England succumbed to the Baggy Greens in a Test match.

While it may have seemed slightly odd to come face to face with sporting and actual royalty in dairy form, such displays had a very real purpose.

"There's this is very romantic ideal that everything can be procured in the empire," says Neal Shasore, head of the London School of Architecture. "Wembley is a big argument. It's a big physical argument for imperial preference."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOver preceding years, arguments had raged about how reliant Britain should be on the non-Empire foreign market - in doing so echoing political debates of more recent times.

"If you can imagine the Conservative Party riven between free traders and people seeking to create and be part of a trading bloc, this is what generates the conditions for the Empire Exhibition," Dr Shasore explains.

At the site's heart stood two enormous hangars - the Palace of Industry and the Palace of Engineering - which contained British products predominately created using materials from across the empire.

This, Dr Shasore says, was a way "to say 'look at what an imperial economy could do. We can get everything, we can service all of our domestic industries'".

"People did believe that the empire was still part of the warp and weft of their lives, and they still believed, I think, across political complexions, that it was viable to the future of the UK," he says.

The National Archives

The National ArchivesOther pavilions representing 56 of 58 territories from the empire were dedicated to the different colonies and dominions and filled with displays to try to give visitors a glimpse of life around the world.

While novelties like a 16ft (5m) tall ball of wool may have amused, more controversial was the use of nearly 300 non-white colonial people who travelled from across the empire to depict places like Nigeria by living and working in the pavilions.

Called "races in residence", such exhibits had been common at similar events previously and, while organisers tried to modernise the idea by shifting the emphasis to education over entertainment, the use of people in displays led to anti-colonialism protests by black London students.

Dr Shasore calls such displays "problematic" but believes by now considering them in the context of aspects like "Rhodes Must Fall' and Colston... we are thinking about these things in different and more critically engaging ways".

The National Archives

The National ArchivesTrade may have been the main motivation for the elaborate event, but there were also other elements going on within Wembley.

Dominions like Canada and Australia hoped to attract people from the UK to move abroad, while at the same time many were worried about the number of single women who were living in Britain as a result of how many men died in World War One.

"There was this idea that there was a surplus women problem so there was quite a lot of encouragement of single young women to emigrate to the empire to stand a better chance of finding a husband," says Prof Sugg Ryan.

Women were again targeted in the Palace of Industry, which featured examples of the most recent advances in domestic living.

This included the "seven ages of woman" exhibit, which was made up of a "tastefully arranged series of rooms" depicting the various gas appliances used during a woman's life - a display one guidebook suggested would prove a particular highlight for most housewives.

Elsewhere, soap manufacturer Pears ran the Palace of Beauty, where figures regarded as some the most beautiful women throughout history, including Helen of Troy, Cleopatra and Mary Queen of Scots, were depicted by real-life models.

It was here that Betjeman complained his father had a tendency to spend most of his time, so feeling abandoned, he would while away the hours in the Palace of Arts, which contained masterpieces by the likes of Turner and Constable, church art and Queen Mary's dolls' house.

Still, there was one place that would always remain the future poet and broadcaster's favourite: "The pleasure park was the best thing about the exhibition."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA larger amusement park than could be found anywhere else in the UK, the funfair was filled with numerous rides seemingly dedicated to causing as much pain and humiliation as possible - a water ride called The Chute, a fun house with a fan hidden in the floor that blew air up women's dresses, and the terrifying-sounding The Whip.

Alternatively, visitors could while away the hours trying out the new Charleston craze in a dance hall three times the size of the Royal Albert Hall, visit a recreation of Tutankhamen's tomb or even take a cage 35ft (10.5m) into the ground to find a working recreation of a coalmine.

For Prof Sugg Ryan, this shows how while the exhibition may have had "worthy intentions about education and trade and imperial propaganda", its visitors only really wanted "to be entertained, they don't want to be lectured".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor some, the greatest pleasure was simply in watching the crowds, with the writer Virginia Woolf declaring: "As you watch them trailing and flowing, dreaming and speculating, admiring this coffee-grinder, that milk and cream separator, the rest of the show becomes insignificant."

Other more leisurely entertainment could be found taking place in Wembley Stadium itself, which at the time was called the Empire Stadium.

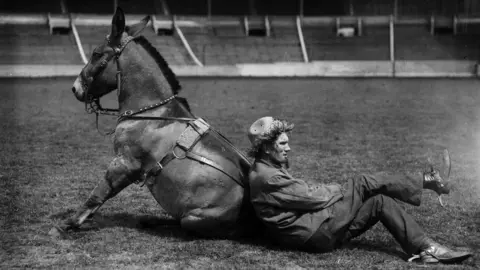

Beyond the usual marching bands, those filling the stands could see a rodeo, Roman chariot-racing, a re-enactment of the Great Fire of London and a live recreation of London coming under aerial bombardment, featuring real biplanes firing pyrotechnics and blanks into the audience before the RAF's planes battled them away.

There were also regular performances of the grand-sounding Pageant of Empire, which had a cast of about 15,000 amateur performers along with some 300 horses, 500 donkeys, seven elephants, llamas, bulls, 730 camels, 72 monkeys, three bears, 1,000 doves, hawks and a macaw.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn attempted retelling of the history of the empire, it featured music composed by Sir Edward Elgar and mobile scenery depicting vast galleons, castles and scenes of medieval England, designed by renowned Welsh artist Sir Frank Brangwyn.

"These were more than just drama, they really were visual spectacles," says Prof Sugg Ryan. "The closest thing to it was the opening of the 2012 Olympics if we're going to make kind of modern comparison."

Beset by bad weather, the pageant proved to be costly, adding to the money woes experienced by the exhibition as a whole. By the time it closed, the British Empire Exhibition was reported to have lost £1.5m (the equivalent of £75m today).

Compare that to the Great Exhibition of 1851 which had six million visitors over six months but made tens of millions in today's money - enough to pay for the creation of a cultural district in South Kensington, which included the Victoria & Albert Museum, Natural History Museum and the Royal Albert Hall.

London School of Architecture/Uni of Portsmouth

London School of Architecture/Uni of PortsmouthDespite the huge numbers who attended the British Empire Exhibition, memories of the two-year event faded as the decades passed.

"If you live in the world where you haven't yet confronted your imperial past, maybe it hasn't seemed that relevant or that interesting and I think because of aspects of its limited financial success, it's been sort of deemed as a failure," says Dr Shasore.

For Prof Sugg Ryan, its legacy can be seen in the memories and ephemera of the event, with numerous postcards, guides, tea caddies and other souvenirs still available on auction websites today.

And then there is the place which for two years tried to bring the empire to Britain's doorstep.

"The history of Wembley Stadium is really tied to the site," she notes.

"I think lots of people don't understand that the whole growth of Wembley as a suburb, and its street names, comes from the Empire Exhibition."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Shasore believes the event "is better-known and remembered than we think, even within the UK", with artefacts from displays to be found in museums across the world having been sold off in the 1920s to recoup some of the losses.

Later this year he is organising a conference involving "makers, designers, curators, scholars from across the globe just to get a sense of what everyone has been doing and thinking about in relation to the Empire Exhibition".

He says: "I think the reason no-one knows much about it is because they were trying to tell a positive story about it and actually that's not appropriate. It's not a positive.

"It's an interesting story, it's a relevant story. It's just not a positive story."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAll images subject to copyright

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]