Watkin's Wembley folly: London's 'Eiffel Tower' that never was

Alamy

AlamyBefore Wembley got its world famous football stadium, a Victorian railway magnate had even grander plans to turn the borough's marshy fields into London's answer to the Eiffel Tower.

Sir Edward Watkin's plan was simple but ambitious - build the tallest structure in the world. The railway magnate had been inspired by the 984ft (300m) tall Eiffel Tower, which was unveiled beside the River Seine in 1889.

He wanted London to have one of its own.

"Like other Victorian men of the era he wanted to make his impact on the world," said Jason Sayer, of the London School of Architecture. "The tower was to be his legacy."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Eiffel Tower was the world's tallest man-made structure when construction finished in 1889.

Initially derided by some for being a monstrous addition to the city's fine architecture, it went on to become a global tourist attraction, recouping its £260,000 construction costs in the first seven months and becoming the perennial back drop for Parisian postcards.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSir Edward wanted Great Britain to have an equivalent. But, instead of building a rival tower in central London, he believed a marsh on the city's outskirts would be the perfect spot.

He had bought 280 acres of land in the Wembley area as part of his grand scheme to build an entire new community, connected to the city of London by the Metropolitan Railway, of which he had been chairman since 1872.

His tower was meant to be the beacon for his new suburban paradise, comfortable homes set in pleasant parklands just a 12 minute train ride from Baker Street station.

The poor would be able to swap the over-crowded disease-infested streets of central London for healthy country air. His park would also encourage city-dwellers to enjoy days out on his railway, with a trip up the tower being the icing on the cake.

Alamy

Alamy"There was a lot of British pride going around at the time and he wanted to typify the country's global achievements," Mr Sayer said. "Part of it was down to him trying to do some public good, although how much the public needs a tower is debatable, but mostly it was down to his own ego."

His park, which included a boating lake, waterfall and various sporting grounds, opened in May 1894 and quickly became popular with some 100,000 visitors in its first few months. Those ambling lazily around the large green gardens would have heard the heavy clanking of metal as work continued on Sir Edward's tower.

But work was not going well.

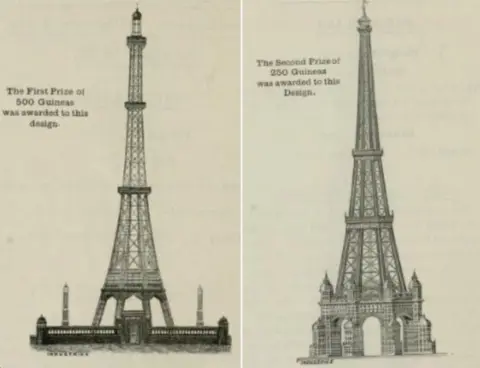

It had been designed by the London architects Stewart, McLaren and Dunn, who had seen off 67 competitors for the 500 Guinea prize.

Public Domain Review

Public Domain ReviewSir Edward had actually approached Gustave Eiffel to take on his tower, but the architect of the Parisian masterpiece politely declined, fearing his compatriots might think him "not so good a Frenchman as I hope I am" if he helped the English build a bigger tower than France's.

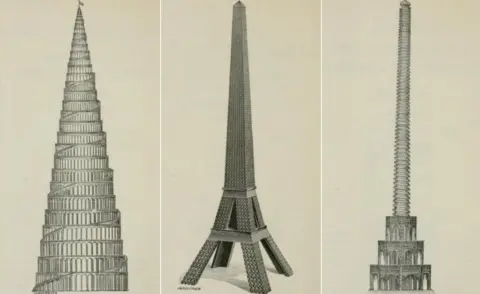

Some of the designs had been fantastical and patently impractical, if not impossible.

One was a 2,000ft high tower shaped like a multi-tiered wedding cake with a working railway spiralling up it. Another was described as an "aerial colony" complete with hanging vegetable gardens and a scale replica of the Great Pyramid on its summit.

Stewart, McLaren and Dunn's winning entry closely resembled the Eiffel Tower, although it was made of steel as opposed to iron and, at 1,150ft (350m), was some 165ft (50m) taller than the Parisian centrepiece.

It was to feature a 90-bedroom hotel, restaurant, theatre, shops, Turkish baths, winter gardens and promenades, as well as a weather station and observatory at the top.

Public Domain Review

Public Domain ReviewBut Wembley was the wrong place for such a project for two main reasons. Firstly, the ground was muddy and marshy and prone to subsidence.

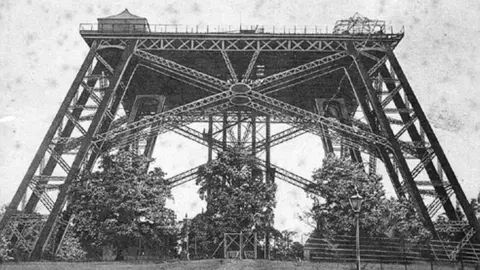

The first stage of the tower, consisting of four giant legs supporting a plateau 155ft (47m) in the air, was completed a short while after the park's opening. But it was soon developing an ominous lean that was even more pronounced two years later.

Alamy

AlamySecondly, it was too far from central London.

"Wembley was not the equivalent of the location of the Eiffel Tower to put it mildly," said Christopher Costelloe, director of the Victorian Society. "People would get there and find there was not much to see, certainly no panoramic view of London.

"If he had built it in Hyde Park it would probably have been a roaring success."

Sir Edward's hopes that his even partially built tower would enjoy the same immediate success as the Eiffel Tower were quickly dashed. Public interest in it waned with visitors donating only £27,000 of the £220,000 required. Sir Edward ploughed £100,000 of his own money into it, but by the end of 1894, work had ceased.

In a bid to reignite public excitement, lifts were installed in 1896 to allow people to get up to the platform. However, during its first six months only 18,500 people paid to do so. The tower once mooted to be named after Queen Victoria became known instead as the "Shareholders' Dismay", "London Stump" and "Watkin's Folly".

Alamy

Alamy Getty Images

Getty ImagesSir Edward, who had also made an ill-fated attempt to dig a Channel tunnel in the 1880s, died in 1901. The following year his much-vaunted tower was closed to the public and in 1906 it was finally torn down.

Though Sir Edward's tower was a failure, his vision for Wembley was not. The park's leisure facilities proved popular and became a venue for large-scale gatherings.

Wembley's place in the list of global icons would be assured when, in 1923, a magnificent new stadium, complete with twin towers, opened to host the FA Cup final between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United.

In 2002, when the stadium was torn down to be replaced by another landmark ground, workmen found large concrete foundations beneath the pitch. They were the first and last pieces of London's answer to the Eiffel Tower.

Getty Images

Getty Images