The peculiar history of the Ordnance Survey

Ordnance Survey

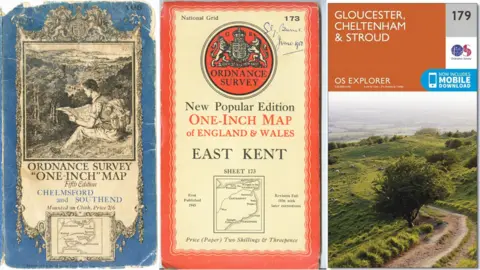

Ordnance SurveyIt's midway through October, so before the days get too short to make it worthwhile, why not grab your compass and hiking boots, shrug on your waterproof and take to the hills. Chances are, if you're a regular walker, you will stride out safe in the knowledge that an Ordnance Survey map secreted about your person means you'll know exactly where and when you got lost.

The history of the organisation known as OS is not merely that of a group of earnest blokes with a penchant for triangulation and an ever-present soundtrack of rustling cagoules.

From its roots in military strategy to its current incarnation as producer of the rambler's navigational aid, the government-owned company has been checking and rechecking all 243,241 sq km (93,916 sq miles) of Great Britain for 227 years. Here are some of the more peculiar elements in the past of the famous map-makers.

Battles and bloodshed

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance SurveyIn the final years of the 18th Century, Europe was in turmoil.

England was braced for invasion by the French and the government's Board of Ordnance (a body responsible for supplying equipment to the Army and Navy and generally defending the realm) needed accurate maps so it could position its troops effectively.

The OS got to work - and by the end of 1794, the coast from Fairlight Head in Sussex to Portland in Dorset had been mapped.

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance SurveyWhen World War One broke out, map-makers were posted overseas to replace existing French maps, which were too small in scale and imprecise.

Over the course of the war the teams produced at least 25 million battlefield maps for use by British troops, and a total of 342 million for the entire war effort.

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance SurveyPointy sticks

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance SurveyIn the late 1940s and early 1950s, teams of tape-measure wielding men swarmed around the country with big pointy arrows. They were urban surveyors using fixed features such as the corners of buildings as markers for map-making.

These markers were called "revision points", and photographs were taken - often with amused or bemused onlookers - to keep track of where these points were.

Education manager at OS, Elaine Owen, has made some of the images taken in Manchester available online. She says they show "a treasure-trove of images which illustrate everyday life while surveyors were going about their daily business".

"Many of the children [in the pictures] would still be alive today. We'd love people to visit the website and search the places and streets they know to see if they recognise anyone, or even themselves. That would be fantastic."

You might also be interested in

Stonehenge in different positions

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance SurveySome of the oldest photographs of Stonehenge were bound in a book in 1867 and recently unearthed from the OS archives.

"Plans and Photographs of Stonehenge" shows the then-head of OS, Col Henry James, and his family having a picnic. The book was made for the agency's officers, and was therefore extremely detailed.

The survey, however, is no longer accurate as the stones have since been rearranged into positions believed by experts to replicate their original ancient layout.

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance SurveyAccording to English Heritage, various stones had been propped up with timber poles from the 1880s, but concern for the safety of visitors grew when an upright stone and its lintel fell in 1900. The then-owner had it made safe, which was the beginning of a campaign to restore and conserve Stonehenge.

The last stones were consolidated in 1964.

People lived there

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance SurveyIn keeping with its military provenance, the original office of the OS was at the Tower of London. But in 1841 fire swept through the Grand Storehouse, threatening both the Crown Jewels and the OS's records and instruments.

Happily, the treasure and the mapping equipment were both saved but the fire prompted the department's move to a new headquarters in an empty former barrack building in Southampton.

Slightly oddly, it wasn't just used as office accommodation - many staff lived on site.

The 1871 census records more than 20 children aged under 12 living at the address.

Mapping Ireland inspired a play

Faber and Faber

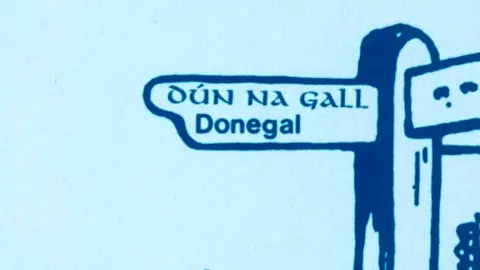

Faber and FaberIn 1824, Parliament ordered then-director general of the OS, Maj Thomas Colby, and his staff across the Irish Sea as an accurate map of Ireland was needed for land taxation purposes.

Brian Friel's play Translations is inspired by the OS survey and the difficulties the English surveyors had with Irish place names and tells the story of Owen, who returns to rural Donegal from Dublin with British army officers who are working on the six-inch-to-the-mile survey.

They translate local place names into English - for example "Poll na gCaorach", meaning "hole of the sheep" in Irish, becomes "Poolkerry" in English.

The character of Captain Lancey is a fictionalised version of Maj Colby.

Mountaintop feasts

Ordnance Survey/Find a Grave

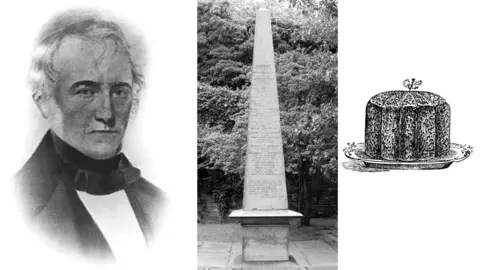

Ordnance Survey/Find a GraveMaj Colby was the longest-serving director general of the OS, who threw himself wholeheartedly into the job.

On one occasion in 1819, he walked 586 miles (943 km) in 22 days in his pursuit of cartographic perfection.

Despite being the boss, Maj Colby always travelled with his men and helped to build the camps - and at the end of each successful mission he would arrange a mountaintop party, complete with an enormous plum pudding to top the celebration off.

Colby House, which was the headquarters of the OS Northern Ireland until 2014, is named in his honour.

There was a special eclipse map

Ordnance Survey

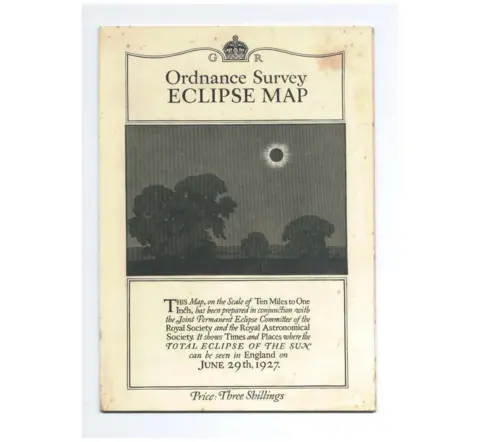

Ordnance SurveyOn 29 June 1927, a total solar eclipse traversed Great Britain and Norway for the first time since 1724.

There was great excitement over the event, and lots of people wanted to know the best way to experience such a thing, so a special map was produced to show the times and places where the eclipse could be seen.

Sadly, most of Wales and England was cloudy that day, but at the site where the Astronomer Royal chose to set up his camera (Giggleswick in Yorkshire) the clouds did part at the right moment, just long enough to capture the 23-second totality.

Waterproof maps were available as early as the 1930s

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf you thought maps were merely for finding the way, think again.

A special waterproofing spray process meant that from the 1930s OS maps could be used as a groundsheet and a cape in the case of a sudden shower.

And if you're likely to spend more time picnicking than hiking, detailed maps - including those of Snowdonia, Dartmoor and the Isle of Arran - are currently available in the form of waterproof rugs.