Touring 21st-Century Devon with a pre-war guidebook

BBC

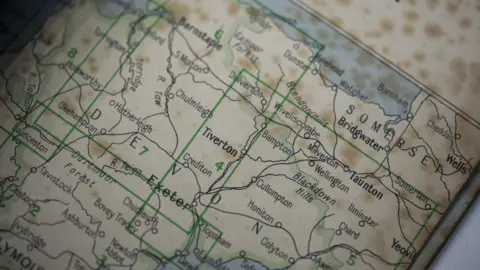

BBCIn 1939, the newly established Penguin Books decided to branch out from its trademark paperback fiction and Pelican non-fiction titles and to try its hand at UK travel guides. Six guides to various English counties were initially published, complete with touring maps, aimed at the motoring middle-class traveller. Emma Jane Kirby has been driving around the UK with those first-edition guides in her hand to see how Britain has changed since the start of World War Two. Last stop: Devon.

I feel a little sad as I trot on to Exmoor. Not just because the heavens have opened and I'm soaked to the skin, but because Devon is the last stop on my tour of Britain accompanied by Penguin's 1939 county guides and I suppose I've become nostalgic for the gentler days described in their pages.

Through a clump of hawthorn trees where I try to find shelter, a herd of wild Exmoor ponies eye us curiously under dark manes. Abbi, my stout, sweet-natured Exmoor trekking pony, gazes back at them seemingly without any resentment or longing to share their freedom. A young mare whinnies to her as we walk on but Abbi doesn't turn her head; she knows there's no going back.

F L Loveridge, who penned the 1939 Penguin Guide to Devon, was a farmer on Dartmoor and was anxious that his readers should admire Exmoor's equine community. Linzi Green, my trekking guide from the Exmoor Pony Centre which aims to promote and protect the breed, couldn't agree more.

"A third of Exmoor is in Devon," she reminds me as she tightens the girth of her pony, Fleeter. "And these intelligent, strong little ponies have always been a part of Devon's history - they're even mentioned in the Domesday book."

Once a devotee of the large horse, Green admits she's now completely sold on the Exmoor pony that never grows above 12 hands three.

"So long as you're not 6ft and you're under 12 stone (76kg), anyone can ride them!" she laughs, as we prepare to canter back across the moor.

"But only a year after your guide was writing about them, they were nearly wiped out completely," Green adds, over her shoulder.

"They were rustled in the Second World War and taken to northern cities as a food source. There were only 40 or 50 left after the war and they were needed for breeding rather than riding, so other breeds overtook them in popularity."

"Bampton," Loveridge informs readers, "is the animated scene of the famous pony fair where large numbers of Exmoor ponies and sheep throng the streets and buying and selling continues all day!"

Not any more.

"Attitudes changed," says Exmoor pony historian Dr Sue Baker, whom we meet back at the stables. "Running foals through a horse fair is quite traumatic and in days gone by people weren't quite so sensitive about how stressed animals got. Now horses are sold privately from farms and it's much better, I think, for the welfare of the animals."

Unsaddled, Abbi and Fleeter are now chomping happily at their hay nets and I ask whether this little pony might come back into fashion one day?

"We have 4,000 Exmoor ponies in the world now," says Baker.

"I love the idea that you can ride on Exmoor on an Exmoor pony and see the herds there and know that people have done this since Celtic times. What I'd love to see is Devon take pride in what they have and to see that pride translated into buying foals. Thank goodness after their terrible fate in the Second World War the ponies came through!"

As our guide, F L Loveridge, was a farmer on Dartmoor, it feels only fair to make a brief detour south-west to admire that moor's ponies too and I choose to visit Haytor, which he assures me is "one of the most visited spots on the moor… with fine views".

It certainly seems to be frequented by the Dartmoor ponies, which have clustered in impressive numbers around the picnic site and the car park, hopeful perhaps of a tourist's discarded apple core.

"They're super ponies but they need a purpose to be here," calls Philippa Whitley from behind the counter of her mobile pasty and coffee van. "They are costly to farmers and they need a purpose so we can ensure their survival."

Whitley explains that she and her farmer husband have long been campaigning on this issue and I ask her whether she has a solution.

"Oh yes," she says, handing me a coffee with a friendly smile. "Pony burgers!"

I gag a little on the coffee.

"Pony or 'taffety meat' is good meat that's low in cholesterol," she continues. "And in times past - in 1939 - your Dartmoor farmer author would certainly have eaten roast pony for his Sunday dinner. So yes, I'd like to see the Dartmoor pony in the human food chain again and I'd like to sell pony burgers from my van."

As I watch a couple of holidaymakers tentatively order vegetarian pasties while taking selfies with the ponies, I wonder whether Devon is quite ready to eat pony again. But how strange that 80 years ago the appetite for pony meat almost wiped out the Exmoor breed, yet 80 years on a resurgent appetite for taffety might help to save the Dartmoor variety.

If you look closely at the inside page of the 1939 Penguin guide to Devon, you'll notice that it's not just F L Loveridge who's credited as the author but also an E A Loveridge, who, on examination of the fly leaf, turns out to be his wife.

"The responsibility for her share," writes Loveridge rather grudgingly, "rests chiefly with her family, as some twenty of their summer holidays were spent at different places in North Devon."

I wonder how poor Mrs Loveridge felt about this dismissive put-down and really hope that, after dutifully making them, she spat in his pony meat sandwiches…

But it wasn't just his wife that our guide's author managed to offend.

"Dawlish itself is one of the quieter modern resorts. The bathing is good but the cliffs are always crumbling and it is unsafe to stay under them," he wrote.

"Now that," chuckles James McKay from the Penguin Collectors Society, "made a certain town clerk at Dawlish Urban District Council very cross!"

McKay explains that, some 15 years after publication, Penguin lawyer Michael Rubenstein (who would later shoot to greater fame as the man who defended the publishing house in the Lady Chatterley obscenity case) was still dealing with the irate clerk, who insisted the cliffs were perfectly solid and that Loveridge's comments were libellous.

Penguin eventually agreed that the comment would be removed from future editions of the guide - a promise that was easy to keep as the guide went out of print soon afterwards. McKay shows me the final tongue-in-cheek correspondence between the lawyers and the Penguin editor, ASB Glover, who wrote in 1954:

"Nonetheless, without prejudice, I don't intend myself to sit under the rocks of Dawlish without putting my umbrella up."

On the cliff path overlooking Dawlish beach and the railway track beside it, a train thunders past at high speed.

"That's the Exeter train!" says councillor Rosalind Prowse, who sits on Dawlish town council. "Did you see the photos in 2014 when the sea breached the wall and the railway track was swinging and floating in the air?"

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe devastating storms of 2014 that shattered the railway line at Dawlish effectively cut off the South West from the rest of the country and left the only rail route into Cornwall hanging like a rope bridge over the sea. Engineering teams worked day and night to repair the line and the then Prime Minister, David Cameron, visited and promised help and funding.

"It cost about £40m to set it right," remembers Prowse. "But it hasn't answered the main problem and that takes us back to your 1939 guide and the talk of crumbling cliffs - the crumbling cliffs are the problem here, not the sea or storms, it's the soft red sandstone that's eroding fast."

Dawlish is now contemplating a more permanent solution to its crumbling cliffs by pushing the railway line on to a causeway further out to sea and stabilising the base of the cliffs between Dawlish and neighbouring Teignmouth. But the go-ahead depends on public consultation and government funding.

"We desperately need a solution for the cliffs," insists Prowse. "The railway is vital for the economy of Dawlish and the South West."

I just hope no-one has told the former clerk for Dawlish Urban District Council.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNone of the Penguin guides ever suggests the names or locations of good restaurants or places to eat, but they do occasionally warn travellers to take care with any local fayre.

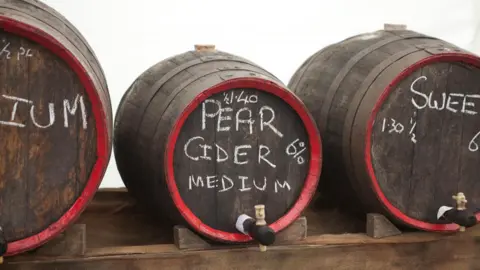

"Most of the cider apples that are grown are now sold direct to factories, but a few conservative farmers still use their own presses," writes Loveridge. "The inexperienced should remember that the potency of home-made cider is very different from the factory-made product, and treat it with respect."

At the South Devon Sunshine Beer and Cider Festival at Newton Abbot, the cider is treated with hallowed reverence.

"Try this Dartmoor one," says Ian Packham, vice-chairman of the local Camra branch as he pours a couple of inches of the cloudy golden liquid into my glass tankard. "It's just over 7% so we'll go easy to start."

I feel the stress of the day dissipate as the warming nectar hits my bloodstream. There are six Devon ciders being shown at this year's festival and I make no protest when Ian's colleague Bob Southwell, who is Camra's chairman in South Devon, opens the tap of another barrel into my glass.

Alamy

Alamy"In 1939, 90% of the farms would have sold cider," Southwell says as he watches me closely to check I'm appreciating the new taste. "But few would have sold commercially. In 1939 cider performed another role - it was a form of payment to agricultural labourers. Part of their wages were subsidised by cider. It was totally illegal but mind you, this is Devon!"

I glance around the marquee and notice that beer is much better represented at the festival - there must be at least 70 beers on offer compared to just six Devonshire ciders. When I look back down at my tankard, it's been refilled - as if by magic.

"It's true that Devon has become famous for beer," says Packham. "We have some very famous brewers around here. But cider has been undergoing a revival here in the last 20 years. The production methods are different from '39 but it's still very natural and the cider is significantly stronger than the fizzy cider you'd buy in a pub."

The fuzziness in my head may be trying to tell me something but I hear my voice asking Bob Southwell where I might buy some Devonshire cider to take home.

"There are 35 cider makers in Devon," he smiles. "Some are very commercial with tasting rooms, others are just farmhouses where you can drive up and they'll bring it out of the barn for you. There's just one difference - in 1939, they'd have come out with it in a jug, today it's in a box with a plastic container inside."

"With the strength written on the box!" adds Packham.

I think of Loveridge's warning as my head begins to swim and quickly make my excuses.

Find out more

Listen to Emma Jane Kirby's report from Devon - the last in her series on 1939 Penguin county guides - for the World at One on BBC Radio 4

Scroll down for links to her reports from Kent, Derbyshire, Cornwall, the Lake District and Somerset

"One Devonshire industry that has increased and become more widely known in recent years is that of pottery making. There is a large pottery at Bovey Tracey, others at Barnstaple..." says my guide.

At the Kigbeare Studios near Okehampton, acclaimed potter Svend Bayer shrugs when I read out this section from the Penguin guide.

After completing his studies at the University of Exeter, Bayer went to work as a thrower at Brannams pottery in Litchdon Street, Barnstaple, where Loveridge advises his 1939 readers they can spend a "most interesting time" watching pots being thrown. Having moved to new premises in the late 1980s, the company ceased all operations in 2005 and the original kiln now stands defunct in the car park of a medical practice.

"By the time I worked there, the tradition was so watered down that it was time to get rid of it," says Bayer. "The world was changing and it was cheaper to import from the Far East or Italy and Spain than it was to make pots there. It was better dead."

Bayer shows me his huge wood-fired kiln and explains how the burned wood ash and embers colour his beautiful stoneware pots. His logs are meticulously and skilfully stashed in huge piles that remind me of the intricacy of dry stone walls.

"I am influenced by South-East Asian pottery, but my roots are definitely in the North Devon tradition," he explains, as we sit in the hot sunshine drinking coffee from his beautiful mugs. "My shapes are based on the North Devon jug and storage jars. I obsess about the North Devon jug!"

He tells me that the North Devon pottery tradition predates that of the more renowned Stoke-on-Trent and that the clay, found only near Barnstaple, is thought to have arrived on a glacier and has nothing to do with local geology. Pots and pitchers would have been decorated with a white liquid slip that was then scratched using a technique known as sgraffito to produce designs or patterns.

"I don't think it would be honest if I decorated in the old style," says Bayer. "If you just copy something, you've missed the point. But if you can capture that spirit, then that's something important."

Twenty-two miles south-east, at Bovey Tracey, the pottery that our 1939 guide boasted of has also gone - but the riverside mill now hosts the Devon Guild of Craftsmen and the largest contemporary crafts venue in the South West. As an educational charity, the guild runs a wide outreach programme teaching crafts in schools and offers mentoring and networking for the county's potters.

"We've got about 75 members working in ceramics today," says the guild's Lisa Cutler, as she shows me around the summer exhibition. "There's definitely still a strong pottery heritage in Devon but with a contemporary take. The industry has declined but we've built up something else."

Through the open windows of the mill I can hear the gleeful, irresistible sound of children's laughter and I'm drawn outside to locate its source.

Crossing the bridge, I see scores of 10 and 11-year-olds dressed in their school uniform jumping into the river and splashing each other with the Bovey's cool water, while their parents and teachers look on, applauding. It's an old ritual, I'm told, to celebrate the end of the children's time at primary school. In September they'll have to knuckle down at big school.

I watch their joyful, carefree faces, dappled in the late afternoon sunlight and suddenly feel terribly emotional. I think too of our insouciant holidaymakers in the summer of 1939 who perhaps also came here to have a picnic and a paddle, unaware or unwilling to believe that in just a couple of months Britain would be at war and that play time and the holiday season would come to a juddering halt.

I close the orange tattered cover of my last Penguin guide and a line of poetry from Philip Larkin floats into my head:

"Never such innocence again."

See also: