Allan Little: The story of Scottish independence - what next?

PA Media

PA MediaOn the face of it, the tide of Scottish independence has turned. With Nicola Sturgeon's resignation, a formidable champion of Scottish statehood leaves the stage.

The movement - famous for the discipline with which it enforced party unity - is visibly divided, caught up in a series of rancorous culture wars. The broad coalition that Sturgeon built up over years - from working class ex-Labour voters to an energetic community of LGBTQ activists - may be in danger of fragmenting.

The pro-Union parties are poised. Labour has most to gain. As the prospect of independence recedes into the distant future, will former Labour supporters drift back, pinning their hopes on a Keir Starmer victory in the UK?

Nicola Sturgeon's departure seems like a defeat for a movement that has been on the rise for a quarter of a century.

So the urgent question now is this: Has the forward march of an independent Scotland been turned back? Does the independence ambition end with her leadership?

Don't be so sure.

I've been reporting on the independence question, on and off, for more than 30 years. In 1992, I spent the night of the general election at SNP headquarters in Edinburgh. The party was expecting an electoral breakthrough - perhaps 10 or 12 seats in the House of Commons - after more than a decade of increasingly unpopular Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher and John Major.

But as the night wore on and Major edged his way to an overall majority, the SNP's confident anticipation turned to despair. The party won just two seats. I became uncomfortably aware that I was the only person in the room who wasn't a party supporter. I felt as though I was intruding on private grief.

Twenty-three years later, on election night 2015, I was a guest at the home of a prominent Labour-supporting family. When the BBC flashed the exit poll at 22:00, predicting (accurately as it turned out) a virtual Labour wipe out in Scotland, and an SNP landslide, the shock in the room was intense. I was intruding again, I thought, on private grief.

What happened, in the years between those two moments, that allowed the independence movement to breach the walls of Labour's Fortress Scotland and sweep through all but three of the country's parliamentary constituencies?

I have been watching, over the course of my adult lifetime, a long, slow generational pivot away from the robust, secure unionism of the Scotland I grew up in.

I have a clear sense of what we have been pivoting away from - just not what kind of Scotland we are pivoting towards.

For me, there is something more telling than the rise of nationalist sentiment, and that is the story of what has happened to the Union itself, to pro-Union sentiment, and to the way Scots have thought about their place within the Union.

It is the story of the falling away, over decades, of much of what it has meant to be British in Scotland.

I grew up in Galloway in the rural south west of Scotland. In the 70s, when I was a child, a sense of British identity seemed unassailable. Even when our constituency returned a Scottish Nationalist MP to Parliament in 1974, one of 11 elected that year, few people saw their victory as a serious threat to the long-term viability of the Union.

For back then, Scotland was a very British country. The economic landscape was still dominated by the great Victorian heavy industries of coal, steel and shipbuilding. The working-class communities they sustained were huge and had proud civic identities.

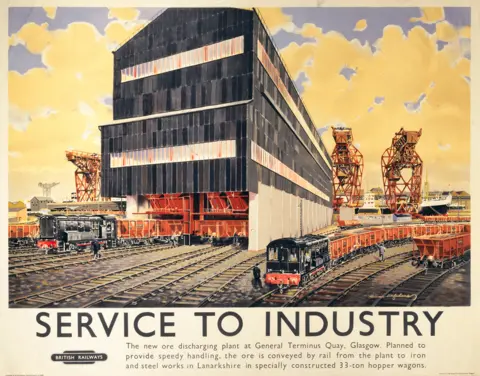

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThose industries were also pan-British enterprises, shared across the four nations. If you were a miner in Fife you were connected, in a community of shared interests and aspirations, with miners in Yorkshire and South Wales. You were in the same trade union, with its pantheon of working-class heroes who'd led the struggle for better wages and safer workplaces. The sense of belonging was powerful.

Scottish Nationalists campaigning in Motherwell, which was dominated by the steel industry, would be told on the doorstep: "But I work for something called British Steel. It pays a decent wage, gives me job security, five weeks holiday and a pension at the end. Are you going to unpick all of that?"

Those communities were bedrocks of British identity in Scotland, as well as of Labour solidarity.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the 1980s and 1990s those industries were swept away. One of the great socio-economic pillars on which British identity had sat crumbled to dust as those communities, over time, fragmented and dispersed, and their old industries slipped, with each decade that passed, further into the middle-distance of collective memory.

After Sturgeon's resignation, I went back to Glenluce, the village I grew up in. I walked past my childhood home. My grandparents had lived in the same street - not far from where my great-great-grandparents had raised their children in the 19th Century.

When they thought of the world, they didn't think of Paris or Berlin or Rome; they thought of Cape Town and Bombay, of Singapore and Melbourne. They had relatives who had settled in the parts of the world that were coloured British Empire pink on the map. When letters arrived from some distant sun-dappled place, the stamps carried the familiar, unifying face of the British monarch.

To those generations, the British Empire was what bound Scotland into the Union. It was a huge, shared British enterprise, built upon a set of values that people across the nations of the United Kingdom broadly shared. We might be radically rethinking the legacy of Empire in our own day, but to them, the experience of Empire was a powerful sustaining force of British identity in Scotland.

BBC / Jonathan Sumberg

BBC / Jonathan SumbergMy parents were born in the 1930s. They lived as children through World War Two and grew into adulthood in a world in which the UK enjoyed immense moral standing.

At the age of 17, my father joined the RAF. He watched the 1953 Coronation on an air base in West Germany, alongside other young men from Bangor and Belfast and Birmingham. The shared Britishness of their young lives was as natural as the air they breathed.

The British Empire would come to an end when they were in their 20s and 30s, but their generation were heirs to a new kind of Britain - the cradle-to-grave welfare state, the new NHS, full employment, social housing (I was born in a council house). But there was something else new for families like ours - a chance that their children would one day make it to university or college. And, in my family, we did.

That post-war Britain was also built on a set of values that were shared across the nations of the United Kingdom; values that achieved cross-party consensus and which prevailed for 40 years.

My generation entered adulthood in the 1980s, at a time when the post-war settlement appeared irrevocably broken down and when the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, offered a bold and radical new vision of Britain's future.

It was, by her own definition, a plan to roll back the frontiers of a state that was outdated, and collapsing under its own weight.

For nearly two decades, the United Kingdom as a whole returned Conservative governments under Thatcher and then Major. But Scotland never embraced Thatcherism - and Conservative electoral fortunes declined until, in 1997, there wasn't a single Tory MP left in Scotland.

In these decades, a long slow divergence in political aspirations took place, with England (particularly the south of England) and Scotland voting for different kinds of Britain. This divergence would resume in 2010. When Gordon Brown's Labour government lost the election of that year, due to a swing to the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats in England, none of Scotland's Labour MPs lost their seat, and many were elected with strengthened majorities.

If the Union had always been at its strongest when it was built on shared values, those values now started coming under strain.

When I was a child, public representations of Scottish identity seemed bizarre. On TV, we had the White Heather Club - women in white frocks and tartan sashes dancing impossibly complicated reels and strathspeys; men in kilts playing accordions and singing kitsch songs about exile and nostalgia. It was caricature and had no connection to lived experience.

But in the 70s and 80s, slowly, that representation of Scottishness began to be eclipsed. Scottish culture was speaking increasingly in its own voice. Much of it was coming from a cohort of young working-class people who'd been (like me) the first in their families to get a college or university education. And a lot of it was explicitly left-wing.

In the 1980s, Labour responded to this shifting social, political and cultural climate, by embracing an idea that had traditionally divided the Labour movement - a Scottish Parliament.

That experience of being governed, through the Scottish Office, by a party that had repeatedly lost elections in Scotland, changed public opinion. Opposition leaders began to argue not just against specific government policies in Scotland, but about the very right of Westminster to impose them. The policies lacked democratic legitimacy because they had, the argument ran, been repeatedly rejected by Scots at the ballot box.

In 1997 when Tony Blair's New Labour came to power, Scotland voted by a majority of three to one to establish a Scottish Parliament. Devolution was the biggest transfer of legislative power from Westminster since the Act of Union in 1707.

And in that tumult, the SNP - long seen as a relatively marginal force - began to reinvent itself, and more crucially, reinvent the independence prospectus. Under Alex Salmond's leadership, the party moved away from its traditional appeal to the politics of national identity - the flag, the literature, the culture and symbols of national sentiment - and towards the politics of social justice. It presented itself to the Scottish electorate as a modern, mainstream European social democratic party.

The independence cause began to converge with the cause of social justice and greater equality. This made the SNP a threat to Labour's dominant position in Scotland. And, though it took a long time, the SNP began to win elections by appealing to traditional Labour voters and by enthusing the young.

This realignment of political allegiances happened under Salmond's leadership. But no-one embodied it more fully than Nicola Sturgeon, from a working class Ayrshire background, who had also been the first in her family to go to university.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen I was reporting on the referendum campaign of 2014, few of the young people who energised the Yes movement wanted to talk about nationality. They wanted to talk about fairness, about the injustices of the growing levels of economic inequality that seemed to them to characterise the UK.

In 2014, Brown was among the first in Labour to see that many of the party's traditional voters were planning to vote Yes. It was the start of a landslip. Many Labour voters jumped ship to vote Yes, and then, the following year, to help the SNP to its astonishing landslide.

Though the Yes movement lost the referendum decisively, the experience changed the political map. The old left-right divide that had defined Scottish politics for a century was replaced: the new fault line was independence.

The Yes movement brought support for independence to 45% - with nearly 85% of the electorate voting, the highest turnout in Scottish electoral history.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is striking that, for all her popularity and the admiration she commands, eight years after Sturgeon assumed the leadership of that movement, the dial has hardly moved. Support for independence still hovers just below 50%.

Why has the unpopularity of Brexit not led to a decisive surge in support for independence? Why did the deeply unpopular premiership of Boris Johnson not change the numbers? And if Sturgeon - probably the most gifted champion of Scottish statehood the movement has ever produced - hasn't been able to build a sustained majority for independence, what chance will her successor have?

The movement she hands over is a cultural as well as a political phenomenon. The idea that an independent Scotland will be a fairer society than the United Kingdom is its core belief.

LGBTQ rights are also at the heart of the movement. But Sturgeon's Gender Recognition Reform Bill opened up a bitter divide in her own party and threatens to split wide open the broad coalition that has been key to the SNP's success.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Bill had cross-party support in the Scottish Parliament: Labour, the Lib Dems and the Greens and even some Conservatives all backed it. But powerful voices in Sturgeon's own party bitterly denounced it, including the MP Joanna Cherry; the leadership contender Ash Regan, who resigned from the Scottish government to oppose it; and Kate Forbes, the finance secretary, who said she would have voted against it had she not been on maternity leave at the time.

But most concerning for the independence cause, opinion polls suggested Scots were not in favour of many of the measures in the Bill. For once, Sturgeon's radical instincts and convictions, which have so often in her career walked hand-in-hand with public opinion, have collided with it.

So this may be a turning point for the independence movement. The era of Salmond and Sturgeon, which transformed the fortunes of the SNP and redrew the map of Scottish and UK politics, is over.

Its signature project - to secure an independence referendum by winning elections - appears to have run into a dead end. Nicola Sturgeon proposed turning the next UK general election into a de facto referendum. An SNP victory would be taken as a mandate to open independence negotiations with Westminster. Few, even in her own party, thought this a viable proposition. The next leader will have to offer independence supporters a credible alternative route to Scottish statehood.

Is there an alternative route? Many commentators think that if support for independence rises to, say, 60% or more and stays there for a sustained period, then a UK government will, in the end, be unable to deny a second referendum indefinitely.

But how to get it there?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDrill into those opinion polls that show support for independence hovering somewhere around 50%, and look at the age demographics. The young remain overwhelmingly in favour of independence - by more than 70% in some age groups. There is even strong support among the middle-aged.

It is only in my own age group, the over 60s, the cohort that still has personal memories a Britain built on a set of shared values and a sense of purpose held in common, where the Union retains commandingly solid majority support.

This leads many nationalists to believe time is on their side - that the fruit of independence is ripening on the tree of age demographics and will one day fall into their lap.

Nothing is inevitable - the young grow older - but those polls suggest that the long, slow generational pivot away from British identity in Scotland has not been reversed. And that is a long-term challenge the Union will have to meet if it is to survive, whatever direction the SNP takes under its new leader.

Follow Allan Little on Twitter

All images subject to copyright