Bus cuts: How a city's bus service was quietly cut in half

BBC

BBCBus networks are shrinking across Britain, but the cuts have gone much deeper in some areas than others, BBC analysis has found. In some places, services have been slashed by more than a third. William McLennan met some of the people who are left behind when the buses stop running.

On a cold February evening, Michael Middleton pulls a thick black beanie over his ears as he walks home beside a thundering dual carriageway after a late shift packing orders in a warehouse.

The number 6 bus used to deliver him home - warm and dry - within about half an hour of clocking off at 22:00, but since 2019 the service into Stoke-on-Trent no longer runs after 21:15.

So instead, he and a colleague follow a litter-strewn path beside the A50, shouting their conversation to each other to be heard over the roar of lorries.

"We just try to block it out," the 61-year-old says. "We try to talk about anything to not think about it."

Across the city, bus services shrank by an estimated 37% in the five years to March 2022. Over an eight-year period from 2013-14, that reduction stands at 50%. In large part, the reductions have not come from the closure of entire routes. Rather, repeated timetable changes - often, passengers are told, in the name of improving "reliability" - have quietly cut services, reducing how frequently a bus arrives, or how late into the evening it runs.

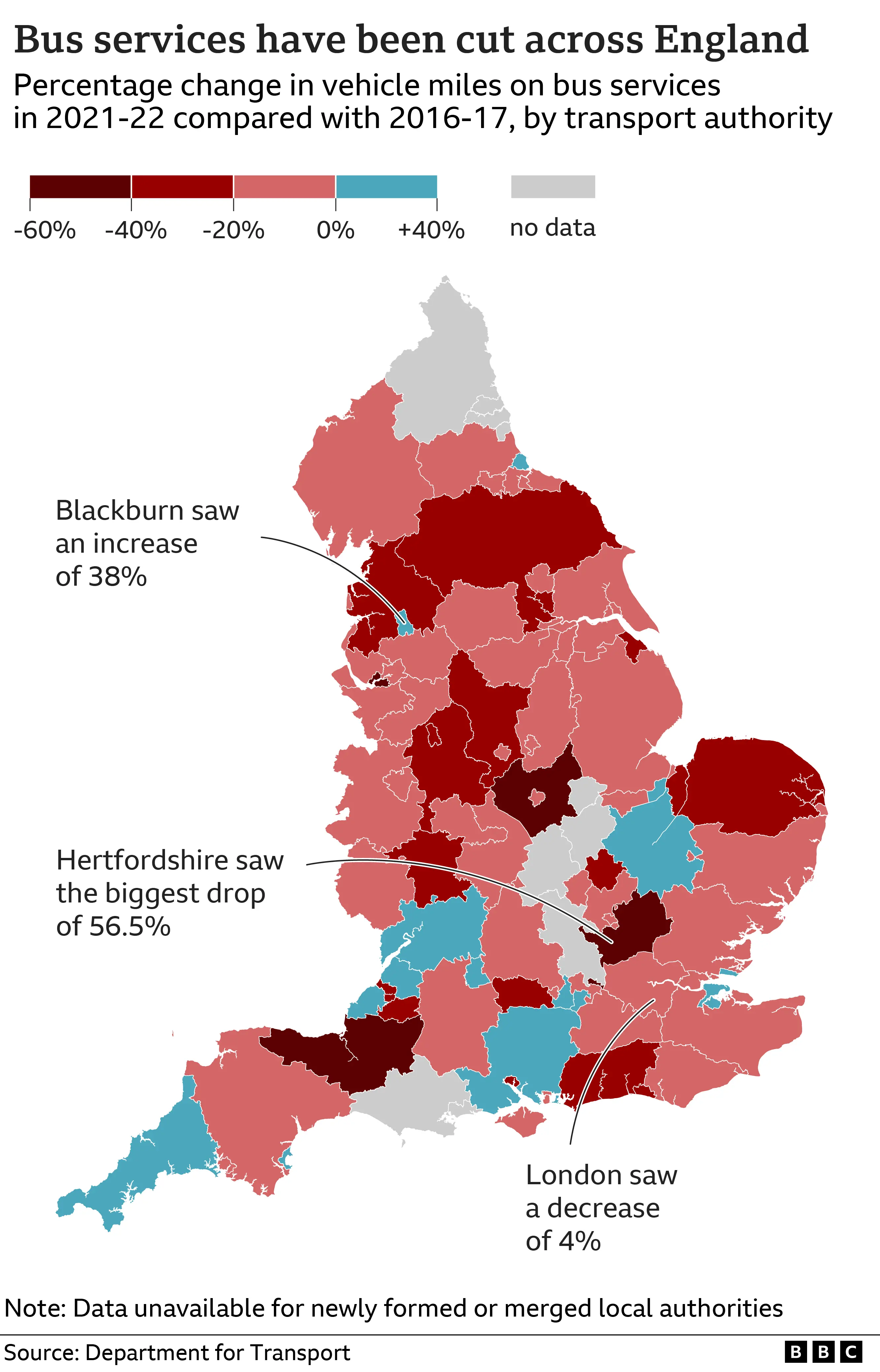

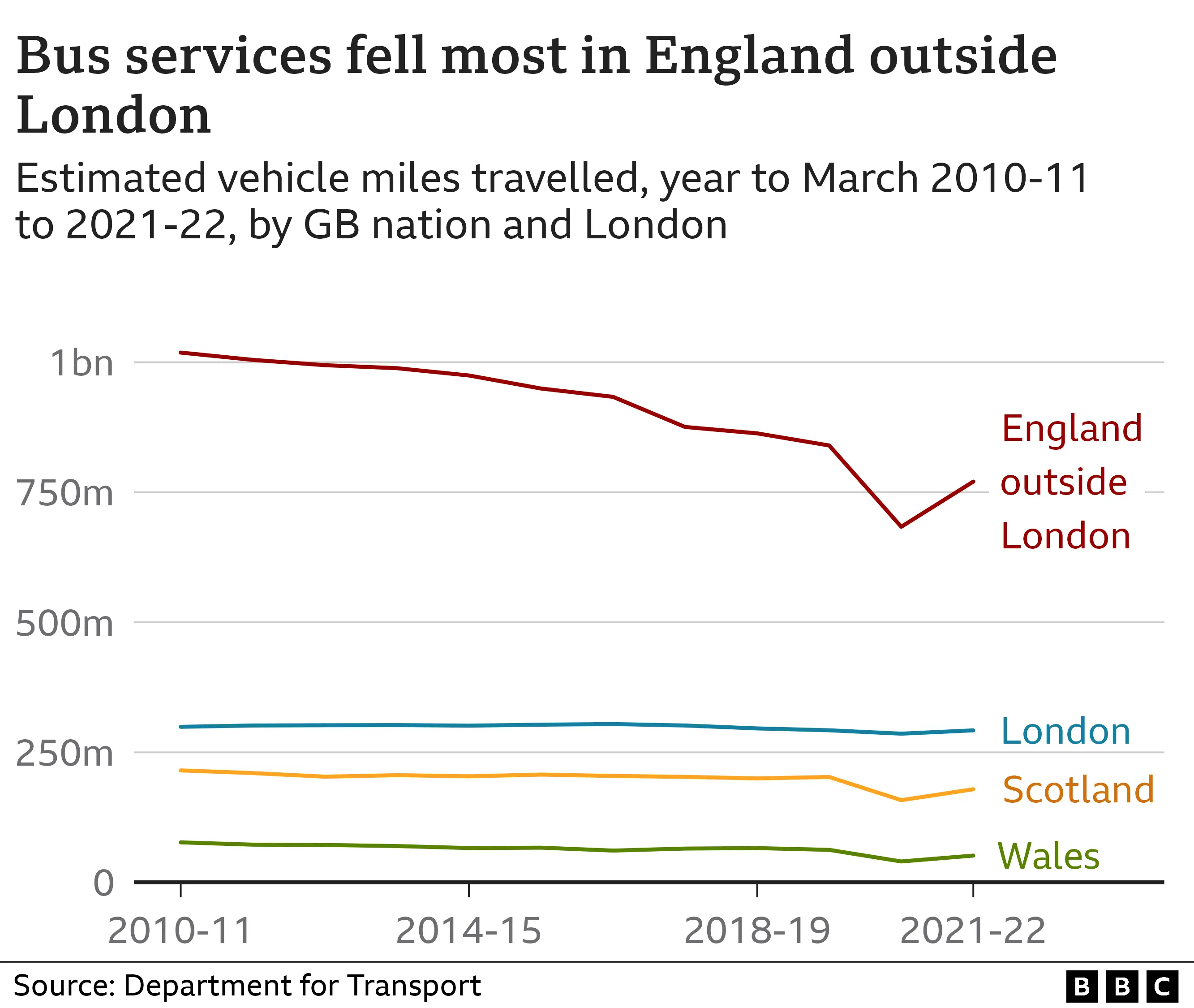

It is an extreme example of a nationwide decline. Across Britain, the local bus network has shrunk by an estimated 14% between 2016-17 and 2021-22, BBC analysis of Department for Transport figures suggests. The total distance covered by buses each year fell by 210 million miles (338 million kilometres).

Demand for buses, which had been gradually declining for several years, plummeted during the pandemic and has not recovered. Passenger numbers across Britain, excluding London, remain about 20% below pre-pandemic levels, according to the latest figures.

For the past three years, the industry has been propped up by government grants totalling more than £2bn.

Despite the decline, buses still account for just under half of all public transport journeys in England. People from lower-income households are both more likely to use the bus, and less likely to have access to a car, official statistics show.

In Stoke-on-Trent, the level of car ownership is below the national average, and in several inner-city neighbourhoods, more than 60% of households do not have use of a car.

"Mainly round here now, it's all minimum wage," says Michael. He worked as a miner in the 1980s - then, after the pits closed, he was a supermarket floor manager, before spending 10 years caring full-time for his wife, who had a rare neurological condition. After she died four years ago, he took the job at the warehouse. "The money they pay you, you can't afford to run a car," he says.

Known as the Potteries, the city is made of six towns strung together by a network of busy A-roads and a shared industrial heritage.

Tens of thousands of people once worked in ceramics factories, but the city has been remoulded by the 20th Century collapse of British manufacturing. In its place, logistics and distribution companies have moved into warehouses across Stoke-on-Trent - now providing about one in 10 jobs.

Yet for low-paid employees, travelling to work has become a logistical nightmare in itself.

Early one February morning, in the far north of the city, Beverley Barnett stands on the pavement next to a chicken shop, the grey ground slick with drizzle.

Her face is lit by the screen of her smartphone, which she swipes compulsively to check whether her bus - the 3A - will arrive on time this morning.

The 38-year-old has allowed nearly an hour-and-a-half to make a journey that would take less than 20 minutes by car. Even so, she is often late into work at the secondary school where she supports children with special needs. Her managers are understanding, but she still worries about the impact on her job security.

"They're as accommodating as they can be, but the kids will be waiting to start," she says. "I do feel like I'm letting them down."

When she moved back to the city 11 years ago, she chose to live close to family, rather than within walking distance of work. At that time, it was a single bus journey lasting about 40 minutes, but the direct service was cut years ago.

She now faces the daily stress of a touch-and-go transfer at the city centre bus station. To make matters worse, she says, the frequency of early morning services was slashed during the pandemic and not restored. Even a short delay now means she will miss her connection and face a long wait for the next bus.

"I'll be checking [the app] all the time, thinking 'are we going to be on time'," she says. "The bus might be only five minutes late, but it adds almost an hour to my journey."

Later that day, Will Lovatt arrives at the bus station on his way home from college. The 18-year-old says unreliable buses regularly cause him to miss the start of lessons, and he fears it is having a "huge impact" on his education.

It is a sunny February afternoon, but he will soon be heading back to his family home in Werrington, on the eastern edge of the city. He would like to spend more time with friends, but the last bus to his village leaves at 19:30.

"It's very restrictive," he said. "By the time you get into something you have to say 'sorry guys I have to go'."

The Campaign for Better Transport has been receiving stories like this on an almost daily basis.

"Even if a bus route is not completely withdrawn, just making it so infrequent that it is impractical has the same impact," says Silviya Barrett, the group's director of policy and research.

Improving bus services - and persuading more people to switch from cars - is a key component of attempts to reach net zero carbon emissions, and must be a priority for the government, she says.

And yet, the costs of bus travel have risen much faster than those for driving. While car owners have enjoyed a 5% cut in fuel duty - which had already been frozen since 2011 - bus passengers have seen fares rise by more than 80% over the past 10 years, according to analysis by the RAC Foundation.

"People are not going to look at the options if it's cheaper for them to drive," Ms Barrett says.

The buses in Stoke-on-Trent, like the majority of services in England, are run by private companies. First Bus - the biggest operator in the city - says cuts to services are a direct result of dwindling demand. Passenger numbers on its services in the city have only returned to about 80% of pre-pandemic levels.

"There has been a gradual decline in demand, both in the Potteries but also across the UK," says Rob Hughes, the company's director of operations.

Even before Covid, the industry had been hit by the decline of the High Street, rise of online shopping and comparative fall in motoring costs.

"The pandemic has accelerated that decline in demand," Mr Hughes says, while rising fuel costs and a nationwide driver shortage have heaped on more costs.

It is a "pivotal time for the industry", he says.

When private operators decide to alter or end a loss-making service, they must first inform the local authority - which has the option of stepping in with funding to keep the buses running. But in Stoke-on-Trent, the council has opted not to do that in recent years. It declined to comment when asked about this.

Across England, about 13% of services are supported by councils, although transport experts say this number has been falling steadily as local authority budgets shrunk.

"Irrespective of the model used to fund bus services, provision needs to match demand," says Mr Hughes. "We obviously can't run buses without passengers."

On Friday, the government announced a three-month extension of the Bus Recovery Grant, which had been due to end in March. It has also extended a £2 cap on single fares, intended to encourage people on to buses.

The Local Government Association had warned thousands more bus routes could be lost without further support. It welcomed the three-month extension, but said the government needed a "long-term, reformed bus funding model with significant new money".

Before the extension was announced, Mr Hughes told the BBC that First Bus had already begun telling local authorities which services could be cut without further support.

The government says it is committed to improving services across the country. It asked all local authorities to work with bus operators to develop "bus service improvement plans", and has awarded £1bn in funding.

Stoke-on-Trent City Council will receive £31m for its plans, which, among other things, aims to reduce fares, increase the frequency of services and provide more buses in the evening.

For Michael, change could not come soon enough. "The hours that we work, the bus services just don't suit," he says. "It doesn't serve us at all."

In his mining days, he never had to worry about getting to work. "The collieries put on their own work buses, so that wasn't a problem," he says. "[They] really looked after you. It was a different world."

He worries what impact the lack of public transport will have on the next generation.

"If they went into the city centre to go to the pictures or something, there's no way back," he says. "They are being cut off from society."

Data analysis by Will Dahlgreen, Becky Dale, Rob England, Jonathan Fagg and Vanessa Fillis

Photography by Emma Lynch