Bus cuts: The UK’s hidden transport crisis – seen from the number 16 bus

Peter Byrne

Peter ByrneBus services have failed to recover following the lifting of pandemic restrictions and have fallen to their lowest levels in decades, BBC analysis suggests. Jon Kelly spent a week travelling on one typical route - the number 16 from Perth to Dundee - to find out what happens when the buses stop running.

One chilly Tuesday evening, Robyn Christie Clarke tentatively makes her way along the uneven grass verge of a slip-road towards her bus stop. Traffic thunders beside her, but what worries Robyn most is whether the number 16B will turn up to take her home this time.

Until a month ago Robyn, 24, from Inchture in Perth and Kinross, was a nursery nurse at Dundee's Ninewells Hospital - but the erratic bus service, plagued by driver shortages and cancellations, meant she could never be sure of making it to her shifts on time.

So instead she found a job with regular hours as an invoicing clerk in Longforgan, the next village along the A90 road. Her dad can give her a lift in the morning. But after work, she is still left with the fear of being left stranded.

"I look at the Stagecoach app thinking: 'Please turn up - otherwise I'm not going to get home,'" she says. "It plays on my mind, especially now that it's getting darker and I'm out here in the middle of nowhere."

In the Carse of Gowrie, a low-lying expanse of farmland and settlements on the north bank of the river Tay, the route 16 bus is a lifeline. Each day the service trundles past a patchwork of fields, simple cottages and detached family homes to workplaces, shops and schools in Perth and Dundee.

But with its reliability already a source of enormous frustration, the operator is planning to reduce the number of times a day it runs.

Peter Byrne

Peter ByrneAnd it is not just here that the bus network is showing signs of strain.

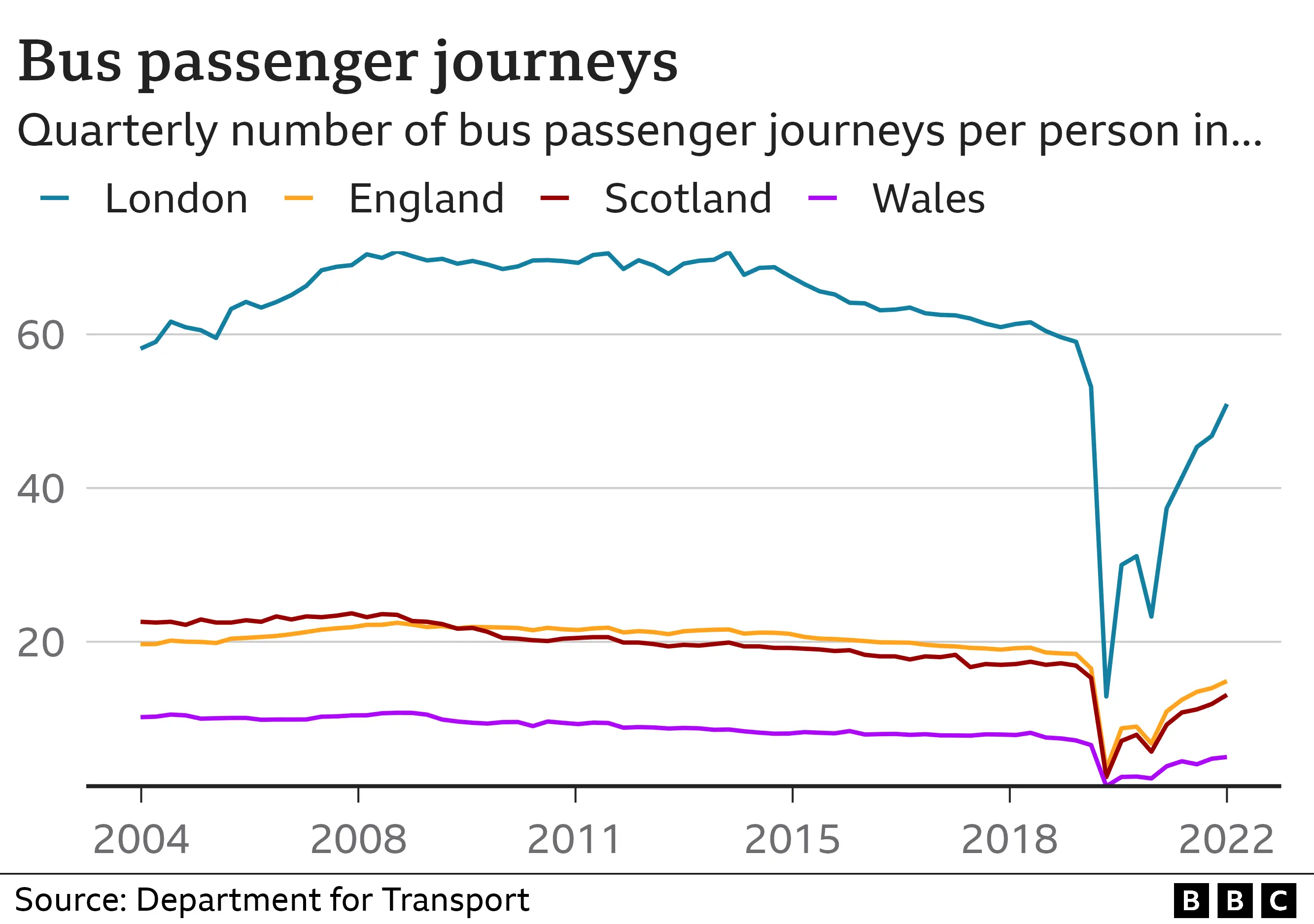

Latest statistics reveal a 20% decline in passenger journeys across Britain compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2018/19 - when services were already the lowest levels since the 1980s.

Scotland and Wales are among those particularly badly affected with experts blaming Covid, Brexit, rising car use and cuts to local authority funding.

Across the UK, bus passenger numbers have returned to about 85% of pre-Covid levels. But bus operators say concessionary travellers, including those who are older or disabled, are taking longer to return - only reaching 72% of pre-pandemic numbers.

Even before the pandemic, the bus network was shrinking. BBC analysis has shown that in the decade to 2019, Britain's bus network lost 134 million miles of coverage. Around Britain, half a million homes - 64,000 of them in Scotland - have no regular buses.

Unlike rail strikes or disruption at airports, problems with bus services rarely generate national headlines.

And yet they remain the UK's most-used form of public transport. People from lower-income households are more likely to take the bus to work than those from higher-earning homes, official figures show. Any effort to cut emissions by boosting public transport will have to take all this into account.

Spend time in any community social media group and you will find stories like Robyn's replicated up and down the country.

Peter Byrne

Peter ByrneWhen a village loses its bus service, for instance, the impact on the people who live there is often huge. They might have to leave their jobs or change the way they shop and socialise.

But with revenues falling, operators across the country say they have to cut services. For instance, from 7 November, Stagecoach has announced that the 16 bus will no longer leave the Carse of Gowrie before 07:00.

One pitch-black October morning, Allan Duffin, 63, is waiting for the 05:54 service to take him from his home in Errol, a few miles west of Robyn's home, to Dundee, where at 08:00 he starts his job as a civil servant with the Department for Work and Pensions.

After he was diagnosed with diabetes, Allan's doctor advised him to give up driving, so the cut means he will be unable to get to the office on time.

As the service arrives, Allan gets on board and looks around the sparsely populated bus. He understands why the decision to cut the service makes commercial sense. "They can't be taking much money from this route," he says.

But aside from his own inconvenience, he feels the village will feel that bit more isolated without the early service. "Call me old fashioned, but when I was growing up this was a public service."

Peter Byrne

Peter ByrneIt was along Perthshire roads like this one where the revolution began that transformed the way the UK's buses operate.

The county is where Stagecoach - now the UK's biggest bus firm - began. Brother and sister founders Sir Brian Souter and Dame Ann Gloag started out with a handful of second-hand buses - and took advantage when public services were thrown open to commercial competition in the 1980s, taking over regional bus companies that had been put up for sale.

Sir Brian became a controversial figure in 2000 when he funded a campaign to prevent teachers discussing gay rights in Scottish schools.

In March 2022 Stagecoach Group was taken over by a German investment fund, but its headquarters remain in Perth. In preliminary results for the end of the year to April 2022, it reported revenues of nearly £1.2bn.

Deregulation did not apply in London, however. According to transport expert Peter White, emeritus professor at the University of Westminster, the UK capital's bus passengers enjoy "a markedly better level of service" compared with other parts of the country.

Transport for London has, however, required a significant amount of financial support from central government since Covid.

Peter Byrne

Peter ByrneIn particular, he says, there is "a very good level of service late nights, evenings and Sundays - whereas even in other big cities, the frequencies are often quite low, and in rural areas they often almost non-existent", he says.

In Perth and Kinross, passengers know this all too well.

Steph MacKay, 37, would rather take the 16 bus from Errol to and from the Perth city centre bar in which she works - it's cheaper than driving, after the cost of parking and petrol have been factored in. She would like to do her bit to help the environment, too.

But a few weeks ago, she says, she was stranded when the last 22:45 service home to Errol was cancelled just 40 minutes before it was due to leave. A frantic Steph rang round her family but no-one was able to give her a lift. To her relief, a friend kindly offered to drive her home.

However, with the taxi journey costing £35-40, Steph cannot afford to take another chance - from now on she will drive to and from shifts. "It's not worth the risk of finishing a 10-hour shift and then having to figure out how to get back," she says.

Peter Byrne

Peter ByrneIn and around Perth, the number of cancelled buses is a source of enormous anger and frustration. As many as 57 scheduled bus departures serving the town have been cancelled on a single day.

Stagecoach blames driver shortages - which has been an issue across the Britain. According to the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT), which represents bus operators, the number of driver vacancies across the country is double what it was in 2019.

"A number of external factors, primarily the fallout from the pandemic and Brexit, have created a perfect storm and led to a greater number of people than usual leaving the industry," Paul White, director of CPT Scotland. The CPT says Scotland has a driver vacancy rate of 14%, compared with 9% across the rest of the UK.

But even within this context, the Perth area appears to have been particularly badly affected. Speaking anonymously, drivers describe feeling overwhelmed at working long hours to plug gaps in rotas.

"Driver shortages have been more acute in Perth than in many other parts of Scotland," says Douglas Robertson, managing director for Stagecoach East Scotland. "Despite operating an average of 94% of our local timetabled services, we share the frustration of our customers at the impact current disruption is having on local communities."

Peter Byrne

Peter ByrneRobertson says the company is working hard to recruit and train new drivers, and it has ordered a new fleet of electric buses for the town. But he calls on local and national government to "invest in innovative solutions" to keep rural communities connected.

On 9 October, Scotland's Network Support Grant Plus - a temporary grant to support the bus industry through Covid - came to an end.

Politicians across the UK have been re-thinking the way buses operate. Free bus travel for young people in Scotland was launched in January. In June, Scottish councils were given new powers to run their own bus services or opt for a partnership or franchise approach.

Meanwhile, the UK government has given English metro mayors new powers to set up Transport for London-style bus franchise systems. Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham's plans to bring services in the region under public control are being watched closely by other authorities.

But all that may take years to come to fruition. For now, the passengers on the 16 bus will continue anxiously checking their smartphones, hoping the service will show up.

Data analysis by Will Dahlgreen and Helen Rosiecka