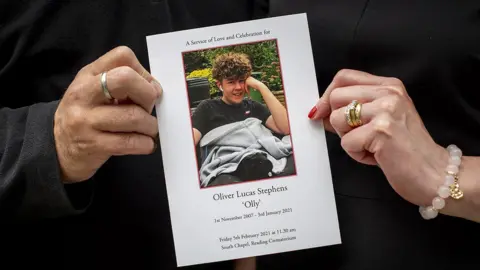

A social media murder: Olly’s story

Stephens family

Stephens family

It was only after Olly Stephens was murdered, in a field outside his home in Reading, that his mum and dad realised the violent and disturbing world their son had been exposed to through his phone. For BBC Panorama, reporter Marianna Spring investigates the role social media played in his death and exposes how a 13-year-old's social media accounts can be recommended violent videos and knives for sale.

Last January, Amanda and Stuart Stephens watched their son from separate windows as he left home, not realising it would be the last time. Olly wandered over to a field, Bugs Bottom, opposite their house - sliders on his feet, his phone in hand.

Fifteen minutes later, he had been murdered.

That phone he was holding would provide the answers to what had happened.

Olly was stabbed to death by two teenage boys in a field behind his house, after they recruited a girl online to lure him there. The entire attack had been planned on social media and triggered by a dispute in a social media chat group.

His parents were shocked to discover the murky world of violence and hate that their son and his friends had inhabited through their phones.

I decided to investigate the role social media played in what happened to Olly - and what 13-year-olds like him are being exposed to.

"They hunted him, tracked him and executed him through social media," Stuart tells me as we sit together on their sofa in their home in Reading.

"Social media is not guilty of the murder, but it did nothing to protect him, and without it he'd still be here."

Stephens family

Stephens family

Stephens family

Stephens familyThames Valley Police say Olly's story stands out because of the huge role social media played in the case. And they fear that the evidence of bullying, and violent videos featuring knives found on the killers' phones, is just "the tip of a very large iceberg".

I set out to uncover what young teenagers are seeing on social media by creating a fake account as a 13-year-old on five social media sites popular with that age group.

Using an AI-generated photograph, we set up accounts for a 13-year-old boy, consulting one of Olly's friends and public accounts belonging to young teenagers in Reading. We wanted to see what a 13-year-old engaging with popular topics for his age - from sport and gaming to drill music and anti-knife crime content - would be exposed to and recommended.

We also wanted to test whether social media sites moderate videos and images of knives similar to those shared by the children convicted of murdering Olly.

After running our dummy account experiment for two weeks, with it liking and following content suggested across the social media sites, as well as his original interests - the results were striking:

- On Instagram, YouTube and Facebook, our 13-year-old account was recommended content such as people showing off knives, knives for sale and posts glorifying violence

- When we used our profile to actively look for anti-knife crime content, the 13-year-old's account was exposed to pro-knife groups, videos and pages on Instagram, Facebook and YouTube

- No action was taken against a post showing off a knife on 13-year-old's account on Instagram, Facebook, YouTube and Snapchat. Tik Tok, however, did remove the content for violating its guidelines on dangerous acts, and the account was warned it was close to being suspended

'Secret world'

When Olly left the house that day he reassured Amanda he had his phone location switched on, so she'd know where he was. It was the Sunday after Christmas, and the family were preparing to go back to work and school the next day. Amanda expected Olly back before dark.

But shortly after he left home there was a knock on the door. It was a boy Olly knew. Amanda couldn't quite take in what he was saying.

"I thought, 'Did he just say Olly's been stabbed?'"

Stuart and Olly's older sister dashed out to the field opposite their home, where Olly was lying in a pool of blood. Amanda followed after them.

"I just held his hand and asked him not to leave me," Stuart says.

Friends, neighbours, dog walkers all tried to help, but it was too late. He died in that field.

"I still look for his feet in the morning at the end of the bed because they would hang over the end," Stuart says. Not seeing them there hits him every time.

Olly's bed is still made up with his favourite duvet cover. Amanda still buys him sweets, and when she vacuums Olly's room - something he used to hate - she still mutters, "I'll only be a minute."

Just before he was murdered, Olly had been diagnosed with autism and, at that time, he most enjoyed gaming and listening to music in his bedroom.

The night after his murder, looking through social media posts about Olly and screengrabs his friends shared with their daughter, Stuart and Amanda began to realise the role social media had played in what happened.

"It's this secret world where you can do and say exactly what you want," Amanda says. "It was a world that we had no idea existed [and] that he was being attacked by it."

Amanda, who would normally use the tracker on Olly's phone to make sure he made it home safely, now found herself using it to check his phone made it into the hands of the police. She followed the signal as it travelled with Olly's body to hospital and then again when it was taken to Thames Valley police station.

'Unprecedented' digital evidence

Detective Chief Inspector Andy Howard was tasked with investigating the world inside that phone. It's a case he describes as unprecedented because 90% of the evidence at Olly's murder trial came from mobile phones - and no child witnesses had to take the stand.

"We were really taken aback by the amount of digital evidence," he explains.

There was enough to convict two boys - aged 13 and 14 at the time - of murder last November. The 13-year-old girl who led him to the park was convicted of manslaughter.

Watch Panorama - A Social Media Murder: Olly's Story at 8pm on BBC One

What struck the police initially about the mountain of videos, photos and screengrabs they began to sift through was the persona that 13- and 14-year-olds linked to the case were presenting online, so at odds with the suburban reality they were living.

There were images shared on Instagram of people holding knives, with balaclavas on and hoods up.

The police also found videos of knives being flicked and shown off, and of boys linked to Olly's murder attacking one another, which DCI Howard told Panorama he believes were being shared "openly and very regularly" on Instagram and Snapchat.

"There is certainly a very unhealthy attraction to filming, recording, acts of really quite serious violence," DCI Andy Howard says.

It was a video posted on Snapchat showing an attack called "patterning" that was the catalyst in a chain of events that led to Olly losing his life.

Thames Valley Police explained that patterning is the humiliation of a young person which is filmed or photographed and then shared on social media. It's forwarded on and on, shared across different social media sites, multiplying the embarrassment for the victim.

In the weeks before he was killed, Olly had seen an image of a younger boy being humiliated and tried to alert the boy's older brother by forwarding it on to him.

When two boys who were in a Snapchat group with Olly became aware he had passed it on, they were furious.

DCI Howard says those boys thought Olly had been "snitching, grassing on them", and that led to the fallout.

BBC/Phil Coomes

BBC/Phil CoomesPolice also found hundreds of Snapchat voice notes from the two boys who fell out with Olly. In them, they discuss attacking Olly and try to recruit a girl to set him up.

The 13-year-old girl who agreed to do this knew Olly in real life, and had met the two boys involved online. Although they all lived locally, they met for the first time on the day of the murder.

The language those convicted used in the voice notes is shocking, with comments like, "You're going to die tomorrow Olly," and "I'll just give him bangs [hit him] or stab him." What's also chilling is their casual and cold tone.

In one voice note, the girl says, "[Male 2] wants me to set him up so then [Male 2] is gonna bang him and pattern him and shit. I'm so excited you don't understand."

None of these voice notes appear to have been picked up by Snapchat - and under the social media app's own policy, it's not possible to report a private message or voice note like this to the site, only the account sending it.

The evidence gathered by the police is just the information required to prosecute - but DCI Andy Howard fears they have only scratched the surface in this case. In his view, it's likely those involved were regularly exposed to violent content - and desensitised to it.

A recent study by the Huddersfield University's Applied Criminology and Policing Centre backs up that idea, finding that social media was a key factor in almost a quarter of crimes committed by under-18s. Most of these were acts of violence that started with confrontation online.

What teenagers see online

In our own investigation, within two weeks of following the kind of content 13-year-olds in Reading follow on their accounts, our imaginary teenager was recommended posts of people showing off knives, knives for sale and videos glorifying violence.

That happened on Instagram, Facebook and YouTube - while on TikTok and Snapchat, the accounts were not recommended this kind of content.

All of these social media sites say that they protect teenage users.

Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook, says it restricts what under-18s can see of "content that attempts to buy or sell bladed weapons".

YouTube says it "may add an age restriction" to content that includes "harmful or dangerous acts that minors could imitate". Our account only encountered one video with an age restriction.

Some of the images and videos of knives were similar to those found on the phones of Olly's killers. We wanted to test what happens when a 13-year-old shares a post like that on social media.

Our fake accounts were private, so as not to expose anyone else to this image and video of a knife.

No action was taken against the post showing off a knife that was shared on the 13-year-old's account on Instagram, Facebook, YouTube and Snapchat.

Tik Tok, however, did remove the post for violating its guidelines on dangerous acts - and the account was warned that it was close to being suspended. That suggests it is possible to detect and remove this type of content shared by a profile under 18. We have now deactivated the accounts.

Our experiment revealed something else striking. Some adverts being promoted to the account on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram were based on his interests and, at times, age-appropriate. That seems to suggest that data from young teenage users can be used to target them - but then isn't being used to protect them from harmful content showing knives and violence.

I wanted to know if the posts pushed to the 13-year-old's account were typical of what teenagers would see so I met up with Olly's friends Poppy, Patrick, Izzy, Jacob and Ben at Olly's memorial bench, metres from where he was stabbed.

Ben had helped me set up the fake account. He and Olly's other friends told me they started using social media long before they turned 13, the age you have to be to sign up to most of the platforms. They all say there were no attempts to verify their ages. Olly's parents say he, too, joined them before he was 13.

BBC/Tom Traies

BBC/Tom TraiesI showed them several screen grabs from the accounts, without exposing them to too much of the content we've been recommended. But the children weren't shocked by the results at all - and admitted they all see knives and violence regularly on their social media feeds.

"I've seen bigger knives to be honest," Jacob says of his own social media accounts.

"We get exposed more to people kind of showing [them] off," Poppy explains, talking about the image people her age try to portray mainly on Instagram, as well as Snapchat.

Ben has seen Rambo knives, and Izzy butterfly blades, which she thinks people share because they are colourful and more appealing.

They all also describe being exposed to cyberbullying on a regular basis - including "patterning" - humiliation videos like the one that triggered the dispute between Olly and the boys who killed him.

All of the social media sites expressed their sympathies to Olly's family. Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook, says that they "don't allow content that threatens, encourages or coordinates violence" and that they have "a well-established process to support police investigations" as they did in Olly's case. They "will urgently investigate the examples raised in this investigation".

YouTube says it has "strict existing policies in place to ensure that our platform is not used to incite violence".

TikTok says "There is no such thing as 'job done' when it comes to protecting our users, particularly young people" and it will "continue to build policies and tools" to help teens and their parents stay safe online.

Snapchat says they "strictly prohibit bullying, harassment and any illegal activity" and "provide confidential in-app reporting tools" on the site.

Hunting for answers

Amanda and Stuart want answers - and solutions - to protect other 13-year-olds on social media, and they want legislators to listen.

BBC/Phil Coomes

BBC/Phil CoomesThe online safety bill is currently passing through Parliament. "This bill is about keeping children and young people safe," Secretary of State Nadine Dorries tells me.

She wasn't shocked to see the results of our experiment. "These platforms know that knife content is being sent to young people's social media feeds," she says. "They can actually put what is wrong right now."

Stuart and Amanda fear that the bill in its current form wouldn't have saved Olly. They want to see more done to verify the age of young users and to limit their exposure to harmful posts - even if the content might be legal, like the violent videos and images of knives our dummy account was recommended.

Dorries says exactly what is considered harmful but legal will be specified soon.

But how exactly could the bill force social media sites to address this?

"I think it's probably easier to keep to the core principle of the bill," Dorries says. "The UK has to be the safest country in the world for children and young people to be online."

The Government is promising harsh penalties if companies don't comply.

"We will have the power to issue multi-billion pound fines and make sure that people within those organisations are criminally liable," says Dorries.

Meanwhile, Amanda says she feels social media companies are not facing up to the reality of what's happening.

"Forget your profits, kids are killing each other," Stuart says.

- Watch Panorama - A Social Media Murder: Olly's Story at 8pm on BBC One