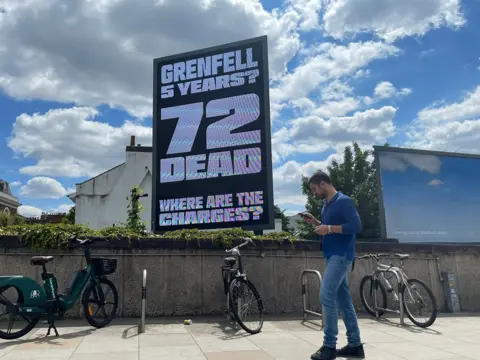

Grenfell: Why are families still waiting for justice?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFive years after fire ripped through Grenfell Tower in west London, a public inquiry has laid bare the string of failures which resulted in the deaths of 72 people. But behind closed doors, police are carrying out one of the largest and most complex criminal investigations ever. When will justice be done and will it result in prison sentences?

In North Kensington, Grenfell Tower's blackened shell is shrouded by plastic wrapping. The loss of its people remains raw.

Grenfell was like a vertical street: 129 flats rented or owned by a community of family, friends and neighbours. They had got to know each other over decades while they waited for the lifts or kept a watchful eye over children playing on the landings.

The government has yet to decide what should be done with the tower. No decisions will be taken until after the fifth anniversary. Some form of memorial is likely.

But Karim Mussilhy knows what should happen. He lost his uncle, Hesham Rahman, and is now a key member of the Grenfell United campaign group.

"In my opinion, nothing should be done with the tower until we get justice," he says - meaning until those he sees as responsible for killing 72 people go to prison.

He may have to wait a long time.

Watch Grenfell: Has Anything Changed? on iPlayer.

The Grenfell Tower public inquiry has been working its way through the evidence since 2018.

It began with moving tributes to the victims, before hearing desperate stories of residents escaping or dying in the tower, as the fire service struggled to cope with a disaster it had barely anticipated and rarely trained for.

There was evidence about the first flames, which emerged from a fridge in a fourth floor flat - and their rapid spread up and through the flammable cladding panels, window frames and insulation which had been installed on its outside walls the previous year in a £10m refurbishment scheme.

A second phase established the disastrous chain of events which led to these dangerous materials being used on the tower.

The painstaking hearings have forced witnesses to confront their failings, sometimes leaving them in tears as every email they sent, or conversation they had, is dissected word by word.

Sir Martin Moore-Bick, a former judge, presides. Richard Millett QC, the inquiry's senior barrister, often leads the questioning, for hour after hour.

Next year a second hefty report will follow a first, already published. Combined, they will be the definitive account of Grenfell Tower and the chain of failure which led to the deaths of 72 people.

There will be more recommendations for the government, and a strong assumption that they will be delivered.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, although the inquiry resembles a court, and has a witness box, it has no dock and no jury. It will not be sending anyone to prison.

In fact, after months of hearings, most of the words spoken by witnesses cannot even be used to prosecute them.

This is because of an agreement with the government's top lawyer, the attorney-general, designed to prevent witnesses exercising their right to remain silent. The inquiry would have been impossible without the deal.

But a parallel police investigation, Operation Northleigh, has been under way for five years, with no limits to how any evidence it obtains can be used.

Deputy Assistant Commissioner Stuart Cundy, who is overseeing it, says that, although he has sometimes been shocked at what he has heard at the public inquiry, "there is nothing which our criminal investigation is not aware of".

He says the police will follow evidence with a view to deciding which cases could be put to the Crown Prosecution Service.

But who are the police investigating, and what for?

The local council

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea owned Grenfell Tower and it was ultimately responsible for the disastrous refurbishment programme.

It could face a charge of corporate manslaughter, but prosecutors would have to show that senior managers took significant decisions which caused deaths.

More than that, what they did would have to be a "gross breach" of their duty to keep the people of Grenfell safe, falling far short of "reasonable''.

But there is a complication. The job of managing council properties was outsourced to an "arms-length" body, the tenant management organisation (TMO), making it ultimately responsible for the long-term safety of Grenfell. The TMO has also been under investigation for corporate manslaughter.

One area of interest to police has been the standing order to residents to stay put in case of a fire. This led directly to deaths.

The council, facing legal threats from the police and multiple civil claims, has admitted a series of failings. It told the public inquiry its building control department didn't properly check that the refurbishment of Grenfell was safe.

Council inspectors didn't ask for comprehensive plans for the cladding system and didn't know what insulation panels would be used, but still signed off the completed work.

Grenfell Inquiry

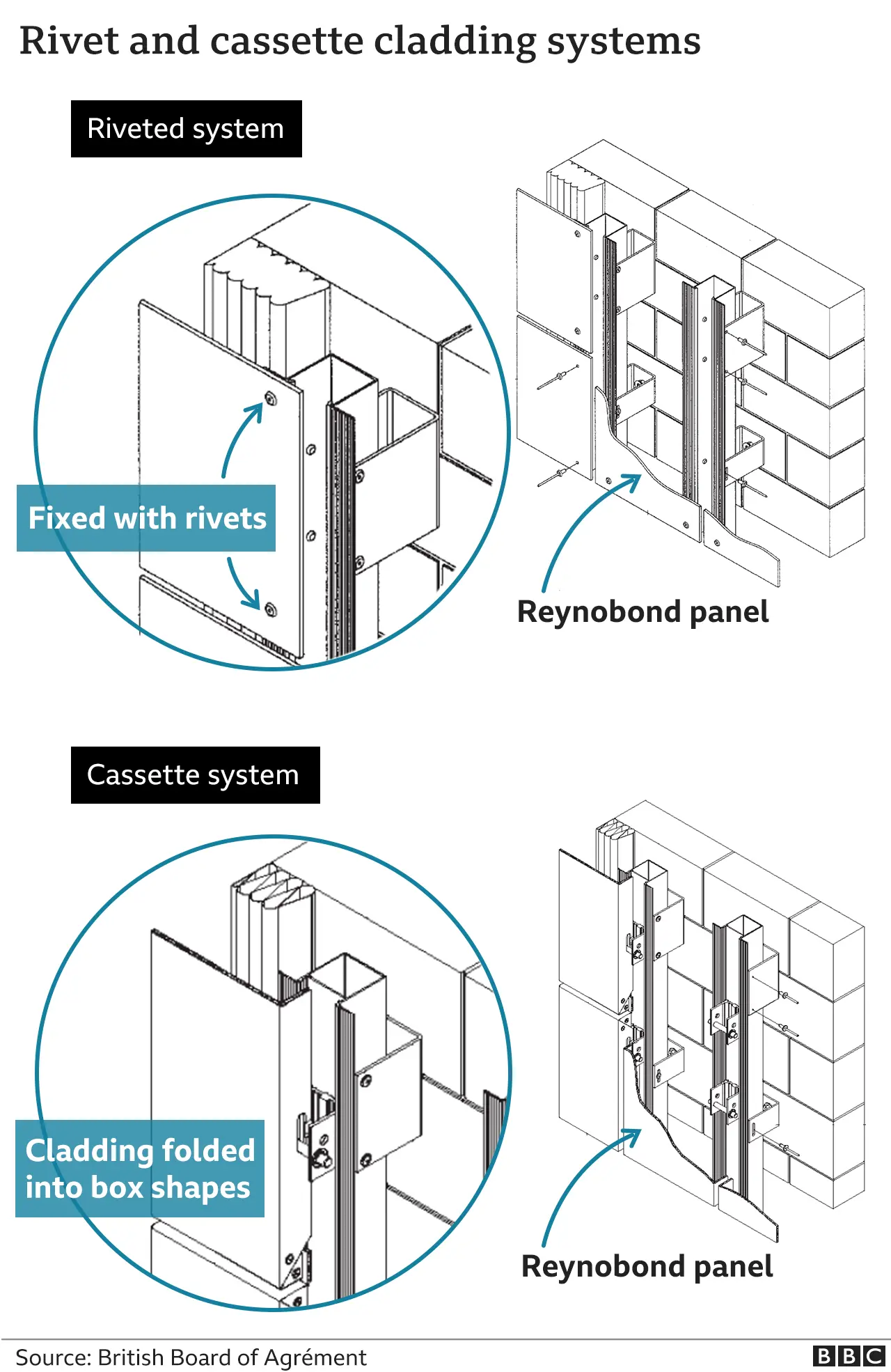

Grenfell InquiryThere is also the council's decision to choose a cheap version of the cladding which was highly flammable. Reynobond PE 55 is made of oil-based plastic. It drips and burns when caught in a fire.

However, the council claims that the architects, designers, cladding suppliers and contractors all recommended the use of that cladding and not an alternative, fire-resistant version.

In those circumstances, the decision could look more reasonable, taking the council out of the range of corporate manslaughter.

The companies involved in the Grenfell refurbishment

The Met's Stuart Cundy says about 700 different companies were connected with the refurbishment of the tower, and there is relevant evidence about 250 of them.

Forty people have been questioned under caution, meaning evidence could be used against them or their employer. Some have been questioned repeatedly.

Police are likely to have examined the advice given to the council and its building firm Rydon by construction experts and cladding specialists. Could these companies end up in the dock for corporate manslaughter?

This is where, what the inquiry came to describe as the "merry-go-round of buck-passing" really begins to turn. The roles of each in refurbishing Grenfell are intertwined and that complexity is at the heart of the challenge for the police. Officers working on the case know that evidence might provide a defence for one company but be used to convict another. Or it might convict both.

For example, many of those involved will claim they firmly believed that cladding and insulation containing flammable plastic was safe to use on tall buildings, because the companies which made these products said so.

Three companies have been under constant pressure during the Grenfell Inquiry.

Arconic, which manufactured the cladding, is a multinational firm, which the BBC investigated in 2018. Police are examining what the company and individual employees knew, and said about, its products.

Technical managers had been told before the Grenfell refurbishment that the cladding was scoring poorly in fire tests when used for designs where the panels were folded into boxes.

The shape encouraged molten plastic to pool and burn during a fire.

Evidence suggests sales managers knew the cladding was to be used on towers such as Grenfell.

Arconic's defence is that meeting fire safety requirements was for building designers, not product manufacturers and that any designs should have been fully tested. They weren't.

Another firm, Celotex, has admitted employees were misleading in the way they described how their insulation boards should be safely used. Their product covered most of Grenfell's walls. Celotex says the fact it was combustible should have been understood by any building firm or architect considering using it.

A third, Kingspan, accepted the insulation it sold for tall buildings was different to the one it had put through safety tests. It also failed to point out the limitations of those tests. Kingspan's boards were used on a small portion of the building's wall.

However, if these companies were charged with corporate manslaughter they would be able to say they were not directly involved in the refurbishment project.

There could be a legal battle over whether they had a duty to protect the safety of people living in the tower.

The government

The council, tenant management organisation, architects, designers, suppliers, contractors and product manufacturers will all be able to point upwards at the government and its failures.

Whitehall officials knew that the industry was badly misinterpreting crucial government safety advice for tall buildings, because the advice was, at best, ambiguous. This didn't change until after the Grenfell fire.

They also knew that cladding fires had engulfed tall buildings abroad, but they were swayed by the fact that deaths from fire in the UK had been falling for decades.

But the government can't be prosecuted for corporate manslaughter.

In addition, if a company was convicted, nobody would go to prison, because a company is not the same as a person. The maximum penalty would be a significant fine.

Edward Daffarn, who nearly died in Grenfell's smoke-filled staircase, accepts this, but he says that some companies and organisations involved are still not taking responsibility.

"A guilty corporate manslaughter charge means you can no longer deny your role," he says.

Could individuals be prosecuted?

Senior police officers have told the BBC they are still examining the possibility of charging individuals with gross negligence manslaughter, which could carry long prison sentences.

Prosecutors would have to prove a suspect had a duty of care to those who died, that they had "foreseen" a risk but done something "far below" what someone with similar experience or qualifications would "reasonably" do.

What they did would have to be a "significant" cause of death, according to the Crown Prosecution Service.

"The bar is high," says Prof Celia Wells, Professor Emerita of Law at Bristol University, "but not impossible. For example, an architect could have acted in a way no reasonable architect would, if they recommended cladding that was flammable."

There are several other options in the prosecutor's armoury.

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 is designed to stop employers putting the public at risk, not just employees in the workplace. Individuals can be prosecuted and a serious breach could attract a two-year prison sentence.

The act could be deployed against any of the organisations involved, including the London Fire Brigade, which was criticised for its lack of planning and training for tall building fires. The Metropolitan Police is also examining possible fraud offences and breaches of fire safety codes.

All of which means that prison sentences are possible following Grenfell, but without manslaughter convictions they may not be lengthy.

Police won't pass their evidence to prosecutors until they see the inquiry's final report - which could be the end of 2023.

The Crown Prosecution Service could take months to decide whether to proceed - and it could be several years before trials begin. Meanwhile, the courts are under enormous pressure.

In short, the Grenfell families will have to wait for justice for a few years longer - and they may not see it before the 10th anniversary of the fire.

Follow Tom Symonds on Twitter