Grenfell's legacy: Should I 'stay put' if there's a fire in my tower block?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs Grenfell Tower burned, residents were told to stay in their flats and 72 people died. Five years on, "stay put" remains the policy for fires in most high-rise buildings.

In the early hours of 14 June 2017 on the 9th floor of Grenfell Tower, Hanan Wahabi's 16-year-old son Zak made a crucial decision. The building had a policy - to "stay put" if there was a fire.

"He decided we weren't going to stay put," Hanan says. "He went out, checked that it was safe for us to leave, came back, took his sister and we followed." She admits she was panicking. Zak became the parent. The family escaped.

But on the 21st floor Hanan's brother Abzulaziz had a different view. "If the emergency services told him to stay put, he'd trust them," Hanan says. Abdulaziz, his wife Faouzia and their children Yasin, Nur Huda and Mehdi remained in their flat. They all died.

Stay put was repeatedly criticised at the Grenfell Tower public inquiry as the wrong advice for people in enormous danger.

So why, five years on from Grenfell, is it still a policy the government believes is safe?

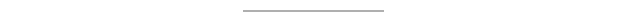

Residential tower blocks are designed so that each flat is a concrete box. If a fire breaks out inside one flat, the theory is the occupants can escape, but their neighbours remain safe, because concrete doesn't burn.

Many British blocks only have one staircase. The stay put policy aims to avoid a situation where people trying to escape prevent arriving firefighters reaching the blaze.

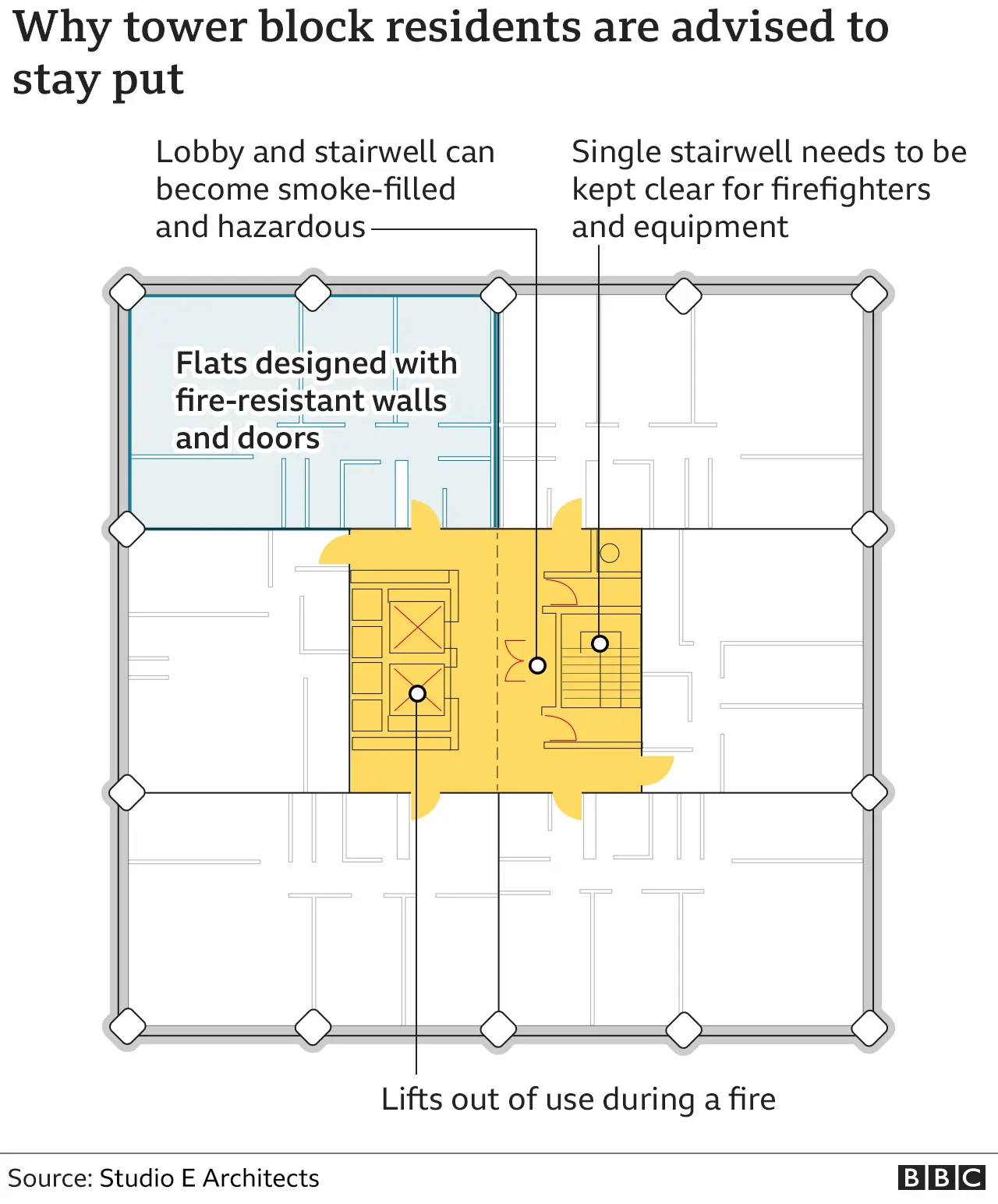

Fire services don't rely on long ladders when tackling fires in tall buildings. They enter the tower and set up what's called a "bridgehead" - a safer area - two floors below the fire.

From there they can connect their hoses to the building's internal water pipes, and head upstairs to tackle the flames.

Inevitably this means propping open fire doors to the stairwell to run hoses, allowing smoke to spread, making the stairs an even riskier escape route.

Watch Grenfell: Has Anything Changed? on iPlayer.

But at Grenfell, the fire spread across the outside walls. In the few minutes it took Hanan Wahabi to escape, flames raced from the 9th floor where she lived to the 17th.

So one of the disaster's biggest lessons is that sometimes "stay put" needs to be "get out".

Prof Jose Torero, an expert adviser to the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, has gone further. This week, he concluded the risk of flames spreading in a fire is too difficult to predict. He said - in the short term at least - abandoning stay put for high rise residential was "essential".

The hundreds of buildings that still have fire safety defects, or unsafe cladding, now have a policy of "simultaneous evacuation" - this is where residents leave as, or ideally before, firefighters arrive.

But Grenfell has changed attitudes. Now people in a fire are not prepared to sit it out even if they are told to do so.

When flames swept across the top of Michael Rudling's block in Deptford, south-east London, in April, thankfully he wasn't there. But if he had been, he'd have got out, despite the building's stay put policy.

"I would have seen it on Twitter before anything else," he says. "People over the road were showing pictures with a big fire on the roof. If I'd seen that I would have thought, 'I'm not going to hang about.'"

The public inquiry into the Grenfell disaster recommended the government and the fire service come up with strategies, that would apply in England, to handle a simultaneous evacuation.

The London Fire Brigade has been practising that scenario. Incident commanders are using new tablets running an app to help them with the mass of information during a major incident.

But simultaneous evacuation could mean residents have to look after themselves.

The average fire service response time is around seven minutes, but lives can still be at risk, according to evacuation expert Elspeth Grant. "It can take 20 minutes for firefighters to begin systematic rescues in a tower." Those 20 minutes could be fatal, she says.

The inquiry recommended nearly two dozen improvements to firefighting, the management of tall buildings and planning for evacuations. The government has yet to implement many of them, though a fire safety order will be issued this autumn and enacted next year.

But in one highly controversial area, ministers say it is not practical to do more.

It is a horrifying fact that 15 of the 37 people with disabilities living at Grenfell Tower did not get out. As a result, the public inquiry recommended any vulnerable person living in a tower be assessed and given a personal emergency evacuation plan, or Peep.

This can involve safety checks to ensure there are, for example, handrails or that the edges of stairs are clearly marked. Peeps can recommend that an evacuation chair is made available, a specialist device capable of rolling down stairs. They also include designated "buddies", either family members or neighbours, to help a vulnerable person in an emergency.

Prof Ed Galea, from the Fire Safety Engineering Group, has been studying evacuations for decades, including rail and air disasters, the World Trade Center attack, as well as Grenfell. He is a strong defender of Peeps.

He says that for every disabled person in Grenfell Tower, there were five residents who could have provided them with potentially life-saving assistance.

"No-one needed to have died at Grenfell. It's possible to have got every single person out. It's doable, it's achievable." He believes a close-knit community like Grenfell would have wanted to protect the vulnerable.

For Georgie Hulme, who lives in a Manchester tower block with safety issues, her evacuation plan provides "huge peace of mind".

Without it, Georgie, who uses a wheelchair, says: "I would need to wait to be rescued by the fire service. Why should disabled people be expected to remain in their flat, whilst their neighbours who can, are told to evacuate immediately?"

Georgie Hulme

Georgie HulmeBut the government says it can't recommend the widespread introduction of Peeps, and it looks likely this recommendation of the Grenfell Inquiry will not be fully delivered.

In a statement to the House of Lords, fire safety minister Lord Greenhalgh said: "How can you evacuate a mobility-impaired person from a tall building before the professionals from the fire and rescue service arrive?

"How much is it reasonable to spend to do this at the same time as we seek to protect residents and taxpayers from excessive costs?

"How can you ensure that an evacuation of mobility-impaired people is carried out in a way that does not hinder others in evacuating, or the fire service in fighting the fire?"

Georgie Hulme's response: "It felt like a real kick in the teeth." She and others told the BBC of their outrage after being described as a "hindrance" to firefighters.

The government estimates that on average 11 people in each tower block is mobility impaired. It says Peeps are not practical.

It believes "buddies" could not be relied upon to be there in an emergency and respond adequately. They would need to be trained and there could be legal consequences for their actions, or lack of action, according to a government consultation. They could be held responsible if anything went wrong.

It estimates that building owners would end up employing staff to facilitate evacuations. Dozens might be needed, and each could cost up to £21,900 per building, per month to provide 24/7 cover.

Instead of personalised evacuation plans, the government's proposals are less ambitious. They involve risk assessments for vulnerable people, and providing information to the fire service so that they can be rescued.

That has an important implication, highlighted by many critics.

Currently the legal onus is on the building owner to keep its residents safe. These changes would subtly move the duty to the fire service to carry out rescues. Disabled residents are now taking legal action against the government.

A government spokesperson said: "Our fire reforms will go further than ever before to protect vulnerable people as we are determined to improve the safety of residents whose ability to self-evacuate may be compromised."

Georgie Hulme's group, Claddag, representing residents living with mobility issues in buildings with safety flaws, has launched a judicial review claiming the government has ignored evidence, as well as equality and human rights legislation.

In a legal letter to ministers, shared with the BBC, the group says: "It is difficult to convey the degree of upset, outrage and betrayal felt by affected disabled persons, bereaved, survivors and residents of Grenfell."