UK's Chagos Islands descendants feel like 'lost nation'

BBC

BBCMore than 50 years ago, Britain claimed sovereignty over the Chagos Islands and evicted its entire population to make way for a joint US military airbase. Decades later, Chagossian families in Britain say they are now being torn apart by UK immigration law.

Daniel Bernard was 10 years old when he was moved to Mauritius from the Chagos Islands.

He remembers a "quiet and peaceful" life on the Chagos Islands, an Indian Ocean archipelago. There was no formal currency, he says, as people would grow their own food and catch fish from the sea.

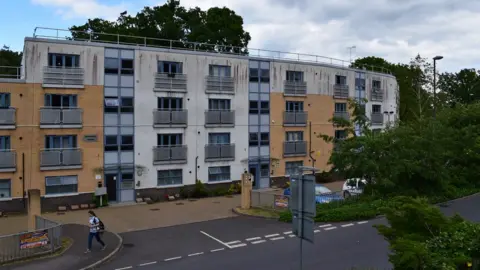

Now aged 74, he lives in Crawley, West Sussex, along with the vast majority of the UK's 3,000-strong Chagossian population.

Daniel returned to Diego Garcia, the island on which he was born, a few years ago, when the Foreign and Commonwealth Office started to organise trips for first-generation Chagossian exiles to visit their homeland.

'Impossible to go back'

"It hurt me to leave and it hurt me even more when I went back," he says.

An imposing military airbase had been built and the small town where Daniel grew up had been flooded by rising sea levels.

"I would love for my children and grandchildren to go back but it's impossible," he says.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryIt is just over half a century since the UK purchased the Chagos Islands from Mauritius for £3m.

Between 1968 and 1974, Britain forcibly removed thousands of Chagossians from their homelands and sent them more than 1,000 miles away to Mauritius and the Seychelles, where they faced extreme poverty and discrimination.

Mauritius says it was forced to give up the islands in 1965 in exchange for independence.

Last week, the UN passed a resolution demanding that the UK hands back control of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius.

The ruling came only three months after the UN's high court advised the UK should leave the islands "as rapidly as possible".

'Sad reality'

For Emmanuel Ally, 21, a third-generation Chagossian exile, the UN vote was "nothing to celebrate".

"The only good thing about it is the recognition that it was wrong for the Chagossians to be removed," he says.

"If you go back now, it's going to be completely different to 60 years ago," says his friend Didier Bertrand, 29.

"That's the sad reality."

So what would they like to happen to the islands?

"Nobody has come up with a plan if it does go to Mauritius," says Didier. "Me personally, I don't want the Mauritian government to have it as I worry they would give it to China or India."

"We would at least like the choice," says Emmanuel. "Nobody has asked us."

"Some Chagossians just want to go there to die," says Didier. "That should be their choice. It's their country."

For young Chagossians, the issues currently facing their community in Britain are far more pressing than sovereignty.

"Help the community here," says Emmanuel. "That's the one thing we are asking for."

In 2002, the British Overseas Territories (BOTs) Act granted British citizenship to resettled Chagossians born between 1969 and 1982.

Many had taken the opportunity to move to the UK in the hope of a better life, having faced hardship in Mauritius.

Shirley-Anne Bontemps is a Mauritian who volunteers in the Chagossian community, and says they now deal with similar issues in Britain.

"It's struggle after struggle," she says, explaining that Chagossians face racism on a daily basis, working minimum wage jobs to afford their visa fees.

"When you talk about sovereignty, this is not improving the Chagossian lives. Nothing has been done to help them. The British government has a duty of care for these people."

'A better life'

The 2002 act's 13-year window for those eligible for British citizenship has left some families divided.

Born in 1968, Jean-Paul Delacroix is one year too old to meet the criteria of the BOTs Act.

The eldest of his siblings, he was the only member of his family not to qualify for British citizenship, but he and his wife Anne decided to follow the rest of his family to the UK, apply for citizenship and hope for the best.

Eight years later and now with two small children, they have had no success and remain in the UK illegally.

The couple - a former carer and a boat painter in Mauritius - cannot work and depend on the generosity of their family.

They live in one room in a small flat that a family member rents and share a set of bunk beds.

"We don't want people to help us like this. We want to work, to have proper money," says Anne.

She has tried to get her three-year-old daughter into nursery but the application forms request proof of residency and Anne fears this will stop her child starting school next year.

"I really want my children to have a better life," Anne says. "My daughter is always telling me she wants to be a nurse."

In 2017, Crawley's MP Henry Smith introduced a private members' bill demanding that all Chagossian descendants have the right to register as British citizens.

But, two years on, the bill has only had its first reading in Parliament with no date set for the next one.

And even if Jean-Paul and Anne did qualify for British citizenship, there is no certainty that their children would.

The Home Office states: "Under current British nationality law, citizenship is normally only passed on to one generation born abroad. This means that grandchildren of resettled Chagossians do not have a claim to British citizenship.

"Visa applications are assessed on their individual merits."

Neither Didier nor Emmanuel have British citizenship and say that in some ways third-generation Chagossian exiles are worse off than their parents. As well as continuing to live with discrimination and racism, many have crippling debts because of visa fees.

The eldest of his siblings, Didier moved to Britain with his family 11 years ago. Aged 18 and no longer classed as a dependant, he was the only member of his family not to get British citizenship.

"They didn't take into consideration that I'm third-generation Chagossian. They just considered me a non-EU citizen," he says.

Didier now has two children of his own who have British citizenship through their mother. Still, he has had no success applying for permanent residency, only managing to obtain two-year working visas.

He works as an airport security officer and has spent almost £10,000 on visa fees.

"I pay my taxes. I pay my national insurance. I pay for the NHS," he says. "That £10,000 could have gone towards my children."

'We don't want to be stuck'

In 2016, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office awarded the Chagossian community a support package of £40m.

But apart from organised trips to the Chagos islands for the first generation exiles, Emmanuel and Didier say they have seen none of this and argue that it should help those struggling with their visa fees.

"Chagossians work in minimum wage jobs," says Emmanuel. "Many are in debt, because they need to borrow for the fees."

Daniel's dream is for his grandchildren to have better lives. "The young deserve to have British nationality," he says. "The Chagos Islands were colonised by the British so it's their responsibility."

"It's like a lost nation," Emmanuel adds.

"We don't want to be stuck as little people."

Some names have been changed to protect identities.