Chagos Islands dispute: UK obliged to end control - UN

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryThe UK should end its control of the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean "as rapidly as possible", the UN's highest court has said.

Mauritius claims it was forced to give up the islands - now a British overseas territory - in 1965 in exchange for independence, which it gained in 1968.

The International Court of Justice said the islands were not lawfully separated from the former colony of Mauritius.

The UK Foreign Office said: "This is an advisory opinion, not a judgment."

It added it would look "carefully" at the detail of the opinion, which is not legally binding.

The UK has previously said it will hand the islands back to Mauritius when they are no longer required for defence purposes.

Referencing that, the Foreign Office said: "The defence facilities on the British Indian Ocean Territory help to protect people here in Britain and around the world from terrorist threats, organised crime and piracy."

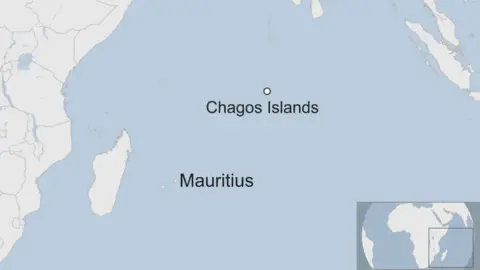

Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf described the UK's administration of the Chagos Islands - located more than 2,000 miles off the east coast of Africa - as "an unlawful act of continuing character".

He added the UK was "under an obligation to bring an end to its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible".

The UN General Assembly asked the court in February 2017 to offer its opinion in on whether the process had been concluded lawfully.

It is half a century since the UK took control of the Chagos Islands from its then colony, Mauritius.

The British government evicted the entire population, before inviting the US to build a military base on Diego Garcia, one of the larger atolls.

Mauritius was in the middle of negotiating its independence from the UK at the time and has repeatedly condemned the deal.

Analysis

By BBC Hague correspondent Anna Holligan

A "blockbuster" of an opinion from the UN's highest court.

The judges' assessment was damning. At the heart of it, the right of all people to self-determination as a basic human right, which the UK violated when dismembering its former colony.

The detachment of the strategically valuable archipelago cannot have been said to be based on free and genuine expression of the will of the people concerned, when one side is under the authority of the other.

As the ruling power, the responsibility lay with the UK to respect national unity and territory integrity of Mauritius as required under international law.

Instead, it divided the territory - effectively using the process of decolonisation to create a new colony.

As part of the advisory opinion the judges poignantly pointed out that all UN member states were under obligation to cooperate to complete the decolonisation of Mauritius. This includes, of course, the US, which operates a military base on the largest atoll of Diego Garcia.

Some of those who were forced to leave their homes on the Chagos Islands in the late 1960s hoped they would be allowed to return - and not just on one of the rare visits authorised by the UK.

Speaking to the BBC last year, Samynaden Rosemond, who left when he was 36, said: "Back home was paradise."

He and his wife, Daryela, moved to the outskirts of the capital of Mauritius, Port Louis.

Chagossians often complain that they are treated as second-class citizens in Mauritius, and they often gather to cook coconut and fish curry and to sing songs about the life they left behind.

Mr Rosemond added: "The British didn't give us a chance. They just said: 'Oh, this is not yours anymore.'

"If I die here my spirit will be everywhere - it wouldn't be happy. But if I die there I will be in peace."

'Explosion of joy'

By BBC foreign correspondent Yasine Mohabuth in Port Louis, Mauritius

Several Chagossians gathered at the Chagos Refugee Group's centre to follow live the session of the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

It was in an explosion of joy that the news was celebrated by both them and their descendants in Pointe aux Sables - a suburb of the Mauritian capital, Port Louis.

The leader of the Chagos Refugees Group, Olivier Bancoult, said it was a historic day.

"I dedicate this victory to the entire Chagossian community that is scattered in several countries around the world," he said.

"It is a great victory as all the time we wanted to go gather on the graves of our families that we lost there [on the Chagos Archipelago]".

Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth said the UK had always emphasised respect for international laws and, as such, expected the country, with which Mauritius has excellent relations, to respect the judges' opinion.