Passchendaele 100: Ypres lights up to remember a dark past

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe lonely, eerie sound of a bugle is one that locals in Ypres, Belgium, are well used to.

But for the thousands of Britons gathered around the imposing white stone memorial of Menin Gate, it may be the first time they have heard a melody that has sounded at that spot almost every night for 90 years.

The Last Post is played each evening by Belgian buglers - volunteers who play the call to remember British and Commonwealth soldiers who defended their town.

But Sunday night was different.

Standing under the vast stone arch were British and Belgian royals, the UK prime minister, members of the armed forces and faith leaders, many carrying flowers and wreaths of red poppies.

They had gathered for a special service to mark a century since the start of the Battle of Passchendaele.

And lining the road leading to the gate were thousands more - many with a personal connection to the battle.

Reuters

ReutersRobert Lloyd-Rees, 75, has been camped outside a coffee shop by the gate since Sunday morning.

"What this town does, to commemorate those soldiers, is remarkable," he says.

It is 60 years since Robert has heard the Last Post, he says, having first visited Ypres with his father Tom, who served at Passchendaele in the Welsh Regiment's Machine Gun Corps.

Robert, who comes from Bristol and now lives in Ottawa, Canada, says the trip has been "tearful".

Kate Palmer

Kate PalmerEarlier that day, he had visited Tyne Cot, a large war cemetery a few miles from Ypres, which he first walked around with his father.

"I remember him stopping at two gravestones and I had asked, 'Dad, what is it?' and he said 'These are my friends'.

"He told me that he had spent two days and two nights behind his machine gun, while two of his comrades lay dead on the sandbags," Robert says.

He does not know how his father, who was just 17 when he signed up in 1914 and had lied about his age, could "withstand such horror", but recalls that he rarely spoke of his wartime experiences.

Getty Images

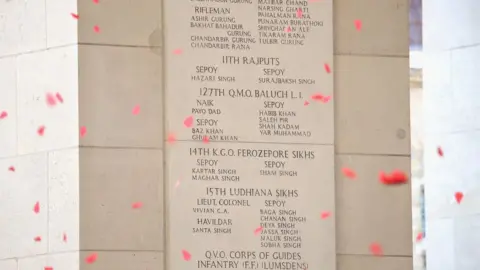

Getty ImagesMenin Gate may be on foreign soil but bears the names of more than 54,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers who fought at Passchendaele, and whose graves are not known.

Father and son Phil and Luke Seeley were also outside the gate, to remember their relative - Sgt Herbert Seeley.

Herbert was injured and sent back to the frontline four times during the war - eventually being sent to Passchendaele in 1917 - but miraculously survived the war.

"My dad says he remembers him sitting in the corner of the room and he would not say anything," says Phil.

"He was bayoneted and sent home to recover, but each time went back knowing what it would be like."

"I've got goosebumps," Phil adds, who says Herbert, from Colchester in Essex, began the war as a private and was by 1918 promoted to a warrant officer.

"We're here to find out more about what it must have been like."

Kate Palmer

Kate PalmerFor three months from 31 July 1917, the battle for a number of ridges south and east of the Belgian town of Ypres resulted in massive loss on both sides, with nearly half a million soldiers thought to be killed, wounded or missing.

Phil and 16-year-old Luke travelled from Colchester through the night to reach Ypres.

"We arrived at around three in the morning, and had to wait outside our campsite for five hours," says Phil.

"We were so tired and hungry and barely able to move, and thought what must it have been like feeling like this and living in total fear for three months."

There was near silence among the crowd as the bugles began playing at 20:00 (19:00 BST). After readings and more music, poppies were released from the arch of the gate to mark the climax of the ceremony.

PA

PAA short walk away from the gate was Ypres' medieval Cloth Hall, which was rebuilt from ruins after the war. For this occasion it was illuminated, and was the focus of much of the sense of excitement in the city, as well as quiet contemplation .

The events continue on Monday, where a commemoration service is expected to strike a more sombre tone.

At Tyne Cot cemetery - the site of 11,000 graves and a memorial to more than 35,000 missing soldiers - royals and relatives will attend an afternoon of song and remembrance.

Tyne Cot's rows of immaculately maintained, white graves are a reminder of the battle's death toll.

One hundred years on, Passchendaele is still synonymous with the blood and horror of the First World War.

"It's ensuring that we don't forget," says Robert, who has a firm plan to ensure that younger relatives know all about and can take pride in what one member of the Lloyd-Rees family did at Passchendale 100 years ago.

He says: "I'll be showing my grandson my father's medals."

PA

PA