Back from the Front: Tracking down WW1 grave markers

Nick Stone

Nick StoneManicured lawns and gleaming white headstones now welcome visitors to the World War One cemeteries of France and Belgium. But a century ago, these soldiers' graves were marked with simple wooden crosses. What happened to them and who are the people tracking them down?

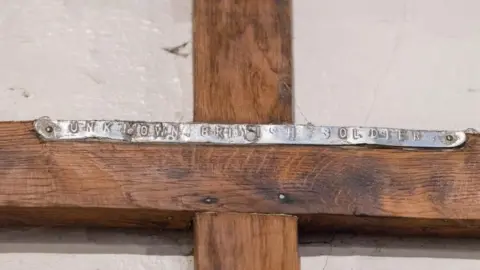

On the wall of St Anne's Church in Sale, Greater Manchester, hangs one such cross. Made from two pieces of wood nailed together, with a sharp, earth-stained point, it has a metal strip reading: "UNKNOWN BRITISH SOLDIER".

It was one of hundreds of thousands of markers indicating the graves of Commonwealth soldiers all along the Western Front. Some are cracked and water-damaged. Many have woodworm. Some even have the original Somme mud varnished on to them.

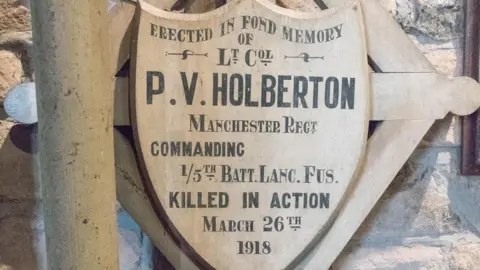

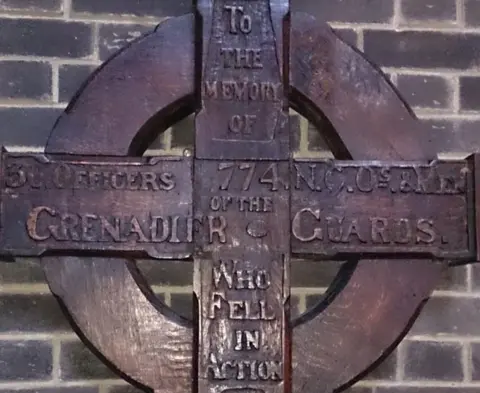

Others are ornate, hand-carved and painted, made in the field by comrades, often from scrap wood or old packing crates, and bearing personal inscriptions. Aviators' graves were often marked by propellers.

Beverley Goodwin / Margaret Draycott

Beverley Goodwin / Margaret DraycottHeritage specialist Nick Stone and a band of dedicated volunteers are tracking down the repatriated grave markers to photograph and catalogue them and create an ever-growing online map and database.

Nick, of Norwich, jokes that when the Returned from the Front project began in July 2016, he thought "it would all be over by Christmas" - just as people reputedly said about the war itself.

Getty Images

Getty Images CWGC

CWGCDuring the war, soldiers were typically buried where they fell or close by. The sheer volume of casualties, and the fact that units were still sometimes under fire, meant this was often done hastily.

Graves were marked for later identification, sometimes by sticks or rifles pushed into the ground, or by wooden crosses. Such was the scale of the killing that crosses were mass-produced and shipped to the front.

Bev Goodwin / Margaret Draycott

Bev Goodwin / Margaret DraycottLater, under the authority of the Imperial War Graves Commission - now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) - these bodies were exhumed and reburied in larger cemeteries, marked with the now-familiar uniform Portland stone gravestones.

The now-redundant wooden markers were then offered to the dead men's families, with each responsible for either collecting them or shipping them home. According to CWGC records, at least 10,000 were returned to next of kin.

Some were given to churches or other organisations, but most of the unclaimed markers were destroyed. Often they were burnt and the ashes scattered across the burial grounds.

Jo Millington

Jo Millington Nick Stone

Nick StoneOf the crosses that survive today, most are in churches but others are in museums, memorial halls, private collections and even schools.

Nick's interest came through a lifelong fascination with World War One. His birthday is on Armistice Day, when his mother would often take out a tin containing her late father's medals, a few lace postcards and his "Dead Man's Penny" commemorative plaque.

"Handling this huge penny with my grandfather's name, Percy James Parr, on it left an indelible mark. I've chased who he was ever since," he says.

Nick's grandfather was 37 when he was killed at Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917.

But there is no marker for him. As Nick writes on his blog, he "did actually vanish, totally, no evidence, no meat or bone, nothing to sew in a blanket and bury in a cemetery".

He is, however, commemorated on the Menin Gate in Ypres, along with the other men in his company who died in the same attack - all of them missing.

Nick Stone

Nick Stone Nick Stone

Nick StoneNick's idea for Returned from the Front came through "thinking out loud on Twitter", and he harnessed social media to recruit volunteers to survey, catalogue and photograph the grave markers.

"The volunteers are great. They are from all walks of life. The youngest is four - she went with her dad - and the adults are from 18 up to 80. Everybody's been pretty marvellous, really," he says.

Nick Stone

Nick StoneSo far, about 70 volunteers have sent in photographs and surveys, with many more providing other helpful information.

Margaret Draycott, a phlebotomist from Liverpool, and colleague Bev Goodwin have catalogued 85 markers, mainly around the north-west of England, but as far away as north Wales, Shropshire and Sussex.

When not visiting the grave marker sites, Margaret is often conducting internet research. "If my family want to find me, they know I'm 'crossing'," she says.

Bev Goodwin

Bev Goodwin Bev Goodwin / Margaret Draycott

Bev Goodwin / Margaret Draycott Philip Draycott

Philip DraycottSome churches are not aware of the significance of the markers, or even what they are. "People have engaged with us and are absolutely blown away that what they have are from soldiers' graves," says Margaret.

Among the markers she has photographed is that of Ellis Humphrey Evans, better known as Hedd Wyn, the Welsh poet killed on the first day of the Battle of Passchendaele on 31 July 1917.

Margaret Draycott

Margaret Draycott SNPA

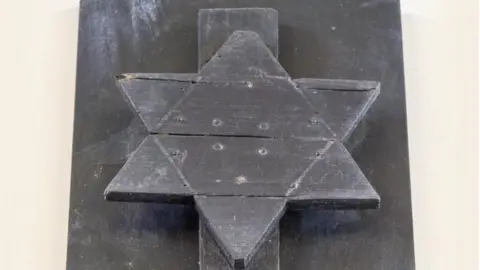

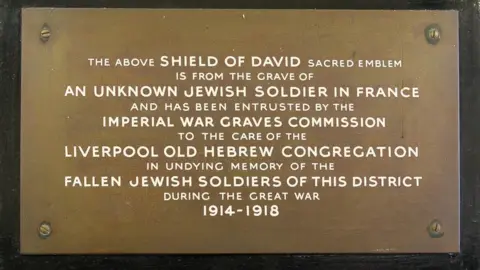

SNPAOne unusual marker is a wooden Star of David, at Broadgreen Cemetery, Liverpool, commemorating an unknown Jewish soldier.

Often it was impossible to identify an individual soldier's remains, and Merseyside has a particular concentration of markers for so-called "unknowns", probably brought back during pilgrimages by churches and other groups.

Bev Goodwin

Bev Goodwin Bev Goodwin

Bev Goodwin

CWCG

CWCG CWCG

CWCGMinistry of Defence colleagues Samantha Fryer, from Swindon, and Dr Alison Wilken, from Lambourn, Berkshire, have surveyed markers in Oxfordshire, Wiltshire, Berkshire and Gloucestershire.

"It's quite nice to know that you are part of a project that's being published that schools and researchers might find useful in the future," says Samantha.

Samantha Fryer

Samantha Fryer Samantha Fryer

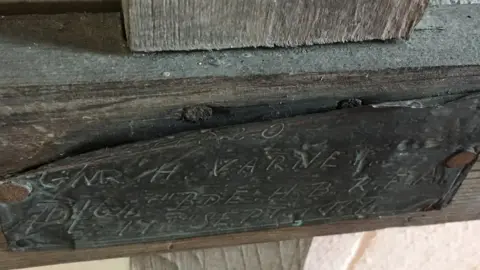

Samantha FryerSt Mary the Virgin Church at Wootton, Oxfordshire, has eight crosses, including one for Gnr Harry Varney, killed in September 1917, aged 30.

It bears an inscription scratched on a piece of metal, possibly from a tobacco or pilchard tin. "To see somebody's writing like that was quite poignant," says Samantha.

"There is an enormous contrast between a lowly gunner's cross with a piece of tin tacked to it and the impressive carved and painted crosses of the officers."

Returned from the Front builds on work by Imperial War Museums (IWM). "It's an absolutely first-class project, worthy of our fullest support," says Ian Hook, who runs IWM's War Memorials Register of more than 68,000 memorials, including 610 battlefield markers.

Only recently, he says, has their significance has been properly appreciated. Many were lost, possibly thrown away by "trendy vicars", who felt that their presence was a tacit endorsement of war, he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany crosses would not even have made it back to Britain at all. "They were offered back to families, but many soldiers were just working lads and the families had lost their breadwinner," he explains.

"Given the opportunity to acquire a cross or buy food or shoes for the kids, what were they going to do?"

Others were lost or destroyed as the fighting shifted and the makeshift cemeteries became battlefields once more.

The fact that any markers found their way home is testament to the work of the CWCG, whose founder Sir Fabian Ware was determined to ensure the resting places of the war dead would not be lost.

"It's important to preserve these relics of the war," says the organisation's chief historian Glyn Prysor.

"They're physical objects brought all the way back from the battlefield and they can help us to connect with that in a tangible way."

Getty Images

Getty Images"The body may be far away in a cemetery but the marker may be in a local church or somewhere else significant. It's making that link between the local area and a global conflict. It's a very special thing."

For now, the work of Nick and his volunteers continues. They hope it will help the markers survive even longer.

Although the many events that have been held to commemorate the war's centenary will conclude next year, Nick says: "I think it's important we don't stop remembering after 11 November 2018."