Tech Tent: Is Arm the future of computing?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWill Arm chips play a dominant role in powering advances in artificial intelligence? Can we find a faster way to build a quantum computer? And what is the secret to getting computers to think like humans?

This week's Tech Tent explores big questions about the future of computing.

- Listen to the latest Tech Tent podcast on BBC Sounds

If you asked most people to name the most influential forces in the technology industry, it is unlikely that many would mention Arm, the chip designer founded in Cambridge 30 years ago.

Yet its technology is in just about every mobile phone and in many of the sensors which are ushering in the "internet of things".

Most of the recent headlines about Arm have centred on the regulatory concerns about its takeover by the leading chipmaker Nvidia. But as if to emphasise that it remains focused on innovation, the company this week unveiled its first new chip architecture in a decade.

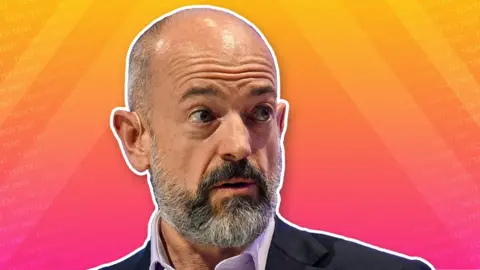

Arm's chief executive Simon Segars tells Tech Tent this is a signal of its ambitions in a computing future where everything is in the cloud.

"We're anticipating that pretty soon every piece of data that is shared touches an Arm [processor] along the way," he says.

"We've been developing capabilities in our processor that allow more and more complex AI algorithms to be run on the processor itself," he explains - and the new chips will also have a focus on security.

Dedicated AI chips are the next big thing in the semiconductor industry, with specialist companies like the UK's Graphcore already making an impact.

Arm is hoping that Nvidia's technology and financial firepower will give it an edge.

But looking further ahead, will it be much-hyped quantum computing that makes a real difference?

A quantum leap?

Giants such as Google, IBM and Microsoft have poured huge sums into quantum research. But some of the claims they've made about progress towards a working quantum computer that can tackle huge real-world problems have later appeared overblown.

Yet two small British start-ups each touted a breakthrough this week.

Quantum Motion, founded by academic researchers from Oxford and London, says it has found ways of using good-old-fashioned silicon chip technology to accelerate the production of qubits, the building blocks of a quantum computer.

"There are lots of weird and wonderful ways that people are trying to build quantum computers using exotic things like superconducting circuits or trapped ions in a vacuum," explains Prof John Morton, co-founder of Quantum Motion.

"What we're trying to do is to take the same kind of technology which is used to build the silicon chip in your smartphone... in order to build quantum computers that can really scale up to the level needed to solve the really big problems."

His doctoral student, quantum engineer Virginia Ciriano Tejel, gives us a flavour of the excitement she felt in the lab when she realised that one electron in a silicon transistor was exhibiting quantum properties.

"You're like, wow, I've measured something really, really small. That's fundamentally something from physics and from nature."

If that is a breakthrough in building quantum computers, another British company - Cambridge Quantum Computing - believes it has shown just how revolutionary such a device could be.

It announced this week what it called "ground-breaking proofs that reveal quantum computers can learn to reason under conditions of partial information and uncertainty."

Dr Mattia Fiorentini, one of the scientists behind the research, says until now this kind of thinking, which comes naturally to humans, has been a challenge for computers.

"Classical computers in particular, are very good at executing procedural tasks, they're not good at modelling probability, modelling uncertainty," he explains.

But he says quantum computers will, by their nature, be capable of dealing with a range of probabilities - "so there seems to be a sort of natural match here."

The hope is that this new type of computer will be able to perform well in areas where there is plenty of uncertainty, from diagnosing medical conditions from scans to predicting where financial markets are heading.

A sceptic might point out that a working quantum computer capable of performing such tasks always seems about five years away. But researchers insist that progress is now accelerating.

"We can measure it and it's happening," says Mattia Fiorentini.

So maybe we had better get ready for an era when a computer can diagnose any disease or play the stock market better than any human.